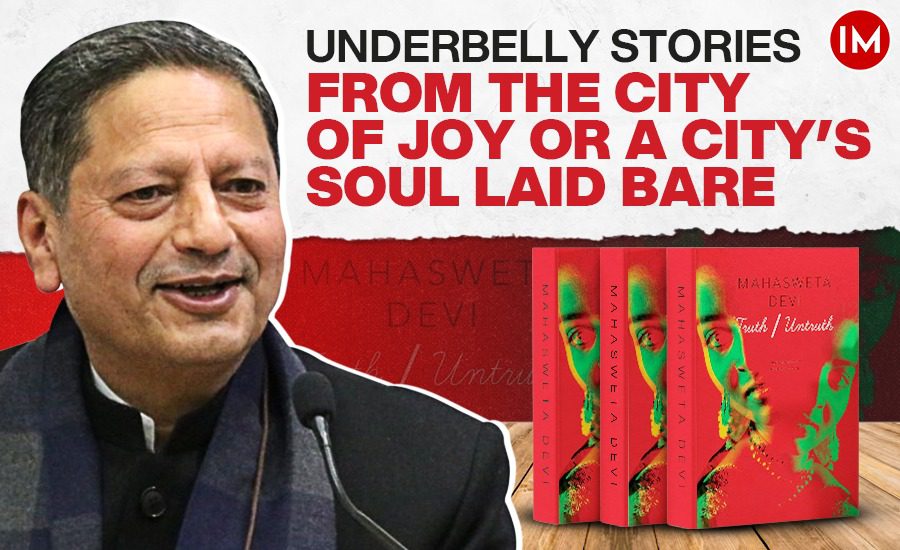

Anjum Katyal’s translation of Mahasweta Devi’s 1986 iconic novella Satya/Asatya brings to light the world of Calcutta (renamed Kolkata in 2001) of those times. This was when the ‘City of Joy’ saw its first high-rise apartments after a decade of the Left-front rule in places like Khidirur – which were ‘neither here, not there’. The blue-blooded Bhadralok of Loudon, Alipore, Camac or Harrington would not deign to live in them, and they were obviously out of reach of the slum dwellers on whose habitation these had come up. They were occupied by nouveau riche contractors, chartered accountants, the freshly-minted management graduates, stockbrokers and young Marwaris who wanted to leave Burra Bazar.

These apartments were gated and boxed, and with all the gadgets that were available in the eighties, they were a sharp contrast to their immediate outside environs. Rather than have the address as a numeric and a pincode, the enterprising marketing team of realtors chose names that bore little semblance to the building or its occupants: the name had to be fancy and fanciful – and thus we have this fast racing narrative set in the house of A-Babu in the Baranmala apartment complex.

The story line is familiar. A-Babu, who had changed his name from Sanatan Pushilal to Arjun Chakravarty to make himself socially acceptable, seduces his maid Jamuna when his wife Kumkum, who is in the family way, is staying with her parents. Kumkum’s family, unlike that of the upstart A-Babu, is an upper middle class Bengali household, whose members solve the Statesman crossword, admire the sculptures of Ramkinkar Baij, the paintings of Jamini Roy and the virtuosity of Ravi Shankar’s sitar. Kumkum’s father is an ex Supreme Court judge, the mother is a socialite whose networking skills helped her husband move up the judicial hierarchy, her brother Bhaskar is a chartered accountant whose wife Bhaswati, a PRO in a corporate firm who has her own private flings.

Their conversations over sundowners are replete with barbs like: ‘Why is that locality so awful, Mimi? This world belongs to Arjun and his ilk… if you leave that neighborhood, will you find domestic help.’ In a comment which was so reflective of the times, ‘If you want a substantial piece of land, you will have to go far off, to Salt Lake, or near the Bypass.’ Technically, Salt Lake is not part of Kolkata, but of the district of North 24 Parganas, with a separate Police Commissionerate!

Kumkum is becoming a mother after ten years of marriage, and Arjun attributes it to the powerful aphrodisiacs prescribed for him by his childhood friend, the ayurvedic physician Keshtokali, but this was also responsible for his sexual overdrive. Jamuna was not an unwilling accomplice, though the first move came from Arjun. When Jamuna realizes that she is pregnant, she decides to extract her pound of flesh. She asks him for a thousand rupees, a princely sum in the days when maids were paid a hundred rupees a month per household along with a winter wrap and a new set of clothes for Puja. She also plans to rob his house with her ‘brothers’ Johny and Tala, and scamp with the loot. Although her husband Moloy had abandoned her four years ago, she harbours a soft corner for him, although of late, she has begun to respond to Mohsin, the caretaker of a tobacco company guest house in the same apartment complex.

If all had gone as per plan, the story would have had a happy ending, almost like a fairy tale. Jamuna would have aborted and recovered, Johny and Tala would have received the money and Jamuna and Mohsin would have started a new life together, but then, something went terribly wrong. Rather than wait for Arjun to take her to a doctor for a proper abortion, Jamuna goes to the resident quack of the slum world, the Lame Doctor to ‘drop the womb’. In a state of stoned stupor, the Lame Doctor gives her the wrong medicine. Jamuna is nauseated to the extreme, and decides to take some rest in Avantika, but the dose is so potent that she drops dead in his guest bedroom.

Arjun is shocked: he knows he has done something to feel guilty about, but murder was not on his agenda. He gathers his wits, and decides to shift the body to the flat next door – that of the Desais – another house in which Jamuna works. Mrs Desai has been mentally disturbed for years after her daughter and son in law died in an air crash, and keeps muttering that she ‘will kill Jamuna one day for stealing her daughter’s clothes’. Mr Desai actually thinks that his wife may have done it, but to save himself and his wife, he decides to shift the body to Mohsin’s room, who in turn decides to shift it back to Avantika, where it is found, lying next to Arjun who is completely sozzled after celebrating, what in his view was the ‘smart disposal’ of Jamuna’s body to Desai’s flat.

Little would he know of the subsequent developments in the storyline, which of course has many loose ends, if one were to look at it as a work of detective fiction. For example, why would Jamuna not be aware of her pregnant state till well into her seventh month? How was it possible for a senior citizen like Desai to lift a bloated body and move it to Mohsin’s room?

But the book is not about the shifting of Jamuna’s dead body from one flat to another. It is about the many mafiosi of the docklands where an upright IPS officer Vinod Kumar Mehta and his bodyguard were bludgeoned to death. It builds the narrative on the don of Khidirur who goes by the nom de plume of Special Person. He wakes up every evening at 6 pm to preside over the numerous operations in his ‘territory’, which includes everything from dispatch of smuggled goods to cocaine to gold, baby food, electronic gadgets, medical chemicals and gun parts.

This world has its hierarchy, obligations and moral codes, for when Mohsin tells a Special Person of his love for Jamuna, he is told: ‘You can marry the girl if you want… but you have a wife. Get her consent, make proper arrangements for her, then go ahead.’ Then there is the mystery writer who ensconces himself incognito in the tobacco company guest house for a few weeks before every Puja to complete his assignments. He enjoys the explicit banter with Jamuna and laments the ‘excessive chastity of Bengali literature which keeps it confined, and riddled with disease’. He wants to liberate his writings by including all the cuss words he learns from Jamuna.

In fine, this offering which has it all – a glimpse of life in the City of Joy, with its beauty and its warts, the many layers of truth and untruth, juxtaposed all at once in a mesh that is almost impossible to untangle. With this, I strongly recommend the winner of the VoW 2024 Award winning translation to our readers.

144 page novella published in hardcover by Seagull Books at an affordable price of Rs 599/.