Every morning in the villages skirting the northern boundary of Kalagarh Tiger Reserve, children step out of their homes not just with schoolbags but with an unspoken risk. Their route to education cuts through a landscape shared with tigers, leopards, and elephants. For years, this daily journey exposed them to danger, a reality quietly accepted as part of life in a forest fringe.

Kalagarh Tiger Reserve, part of the larger Corbett Tiger Reserve, is among India’s most wildlife-rich landscapes. It also represents one of the country’s most complex human–wildlife interfaces. While conservation success here is well-documented through its high tiger density, the social dimensions of living alongside wildlife often remain invisible.

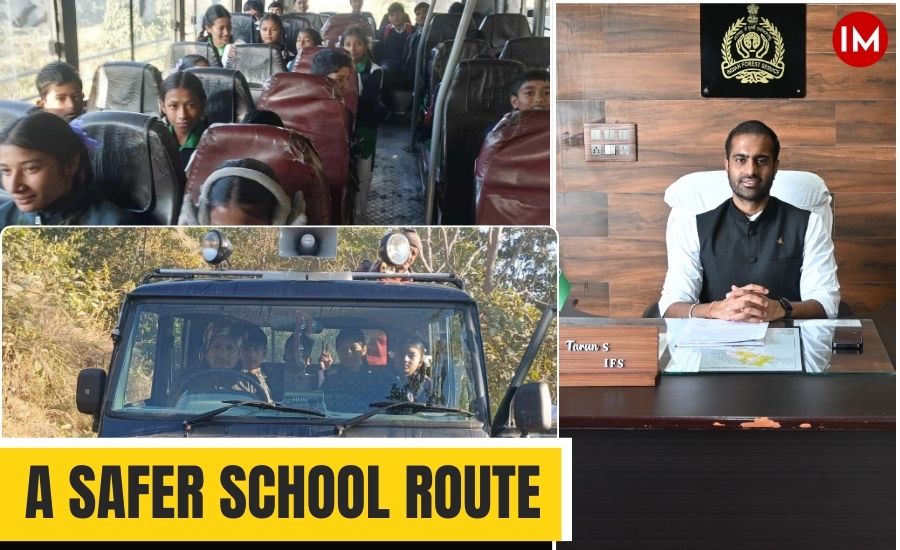

That invisibility changed with a simple but transformative intervention: a dedicated bus service for school-going children.

WHY KALAGARH EXISTS WITHIN CORBETT’S LARGER LANDSCAPE

Kalagarh Tiger Reserve is not a new conservation island carved out unnecessarily. Administratively, it forms a distinct division within the Corbett Tiger Reserve, which also includes Ramnagar. Together, these units make up what is commonly referred to as Corbett.

Geographically, Kalagarh stands apart. It is shaped by a mix of grasslands, moist and dry deciduous forests, and riverine systems defined by the Ramganga River. This habitat diversity supports not only tigers but a wide range of prey species, birds, reptiles and smaller carnivores.

According to IFS officer Tarun S, Deputy Conservator of Forests, Kalagarh Tiger Reserve, the area’s ecological value is inseparable from its human reality. “Corbett has one of the highest tiger densities in the country, and Kalagarh is part of that success story,” Mr. Tarun shared in an exclusive interview with Indian Masterminds.

But success brings pressure. As wildlife populations grow and disperse, interactions with surrounding villages become inevitable, particularly along the northern boundary where settlements lie close to forest edges.

CHILDREN, CONFLICT, AND A DAILY RISK NO ONE TALKED ABOUT

Negative human–wildlife interactions in Kalagarh are not theoretical. In early December, a woman lost her life in a wildlife encounter, a reminder of the fragility of coexistence. Tigers and leopards are responsible for most incidents, with elephants affecting specific pockets.

For children, the risk was amplified by something basic: the absence of public transport. Many walked several kilometres to school, often at dawn or dusk. Some hitchhiked. A few families hired private vehicles, but most could not afford to.

“The most worrying part for us was that children were walking through forest stretches at timings when animal movement is high,” Mr. Tarun explains.

Until recently, the Forest Department filled this gap using Quick Response Teams. Forest guards and rangers escorted children in departmental vehicles. While effective, the arrangement depended heavily on individual officers and stretched already limited resources.

As Tarun puts it, “Using QRTs to escort children works only as long as someone is personally driving it; it’s not something the system can carry forward.”

FROM TEMPORARY ESCORTS TO A PERMANENT BUS ROUTE

Recognising that safety could not depend on goodwill alone, the Kalagarh Tiger Reserve worked with the State Transport Department to design a long-term solution. The result was a dedicated bus service running along the northern boundary, connecting key educational hubs.

In addition, the timings of existing buses were rationalised to align with school schedules, ensuring safe travel both ways. One additional bus was introduced immediately, with another planned at the regional level through coordination with Dehradun.

“This was about moving from ad hoc mitigation to a system that doesn’t collapse when officers change,” Mr Tarun says.

The impact was immediate. On the very first day, buses filled beyond expectations. Photographs sent by the depot manager showed children packed into seats that had previously remained empty. Over time, usage has only increased.

What made the initiative notable was not just its success but also its simplicity. It required no new infrastructure, no large funding package, and no enforcement. It worked because it aligned public transport planning with ground-level conservation realities.

STRENGTHENING COMMUNITIES BEYOND TRANSPORT

The bus service is part of a broader strategy focused on reducing conflict by empowering local communities. Eco-Development Committees (EDCs) are being strengthened with financial support and equipment, giving villagers a stake in conservation outcomes.

A major focus area is the removal of lantana, an invasive species that dominates forest edges and village commons. Lantana provides cover for carnivores, increasing the chance of sudden encounters when people collect firewood or graze cattle.

“Wildlife doesn’t plan attacks; most incidents happen because humans and animals surprise each other in lantana thickets,” the officer explains.

Local residents are now being engaged to clear lantana using bush cutters and solar-powered equipment. This creates livelihood opportunities while improving visibility in shared spaces.

The Reserve is also piloting AI-based camera systems in five sensitive villages. These cameras will provide real-time alerts on animal movement, allowing villagers to take precautions before stepping out. If successful, the model will be expanded across the boundary villages.

COEXISTENCE IS A SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Despite these efforts, Tarun is candid about the limits of departmental action. Conservation, he argues, cannot succeed if responsibility is externalised entirely onto forest officials.

“People often say, ‘your tiger came into my village,’ but eventually officers get transferred; the tiger and the village remain,” he says.

Simple behavioural changes—avoiding movement at dawn and dusk, keeping surroundings clear, supervising children and elderly residents—can significantly reduce risk. Building trust and shared ownership, rather than fear-driven narratives, remains the biggest challenge.

IFS officer Tarun’s own journey into the Indian Forest Service reflects this long-term view. With a background in engineering, NGO work with organisations like the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Nature Conservation Foundation, and a stint at Infosys, he chose the Forest Service deliberately. He cleared the exam in his fifth attempt, driven by a sustained engagement with wildlife conservation rather than a backup plan.

The school bus rolling through Kalagarh’s forest-edge villages every morning may appear ordinary. Yet it represents something larger—a reminder that conservation is not only about protecting wildlife but also about designing systems where human lives, especially children’s, are not placed at risk in the process.

If replicated across other tiger reserves, this model could quietly reshape how India manages coexistence in its most sensitive landscapes.