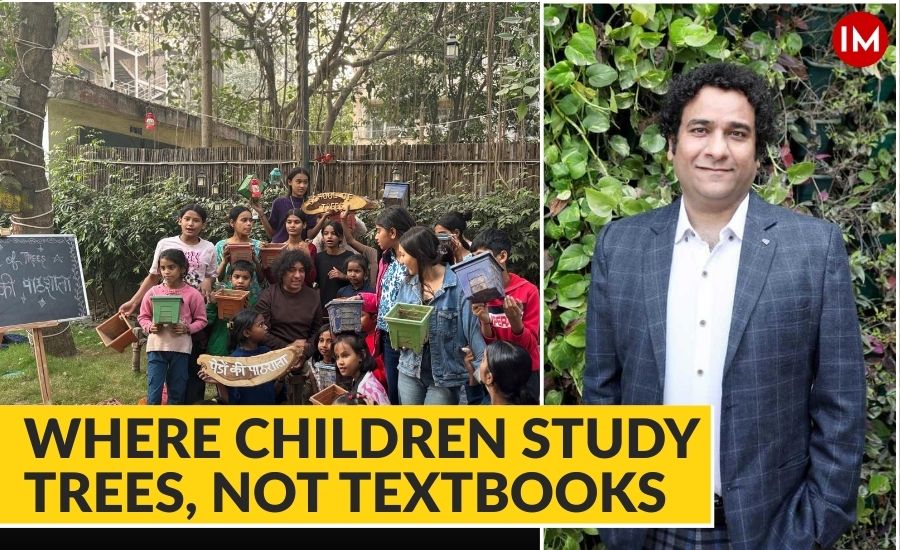

When IRS officer Rohit Mehra speaks about trees, he does so with the enthusiasm of someone discovering nature for the first time—not as an expert, but as a learner who wants children to learn with him. What he and his wife started in their society garden has now quietly taken the shape of what he calls the world’s first “School of Trees (Pedo ki Pathshala)”—a weekend learning experience designed entirely around touching, observing, and understanding trees.

The idea is simple. Every Saturday and Sunday, children from Class 2 to Class 10 gather for a two-hour session: 75% practical activities and 25% basic theory. No textbooks, no complicated lessons—just trees, soil, seeds, sunlight, and questions.

“Search anywhere on the internet,” Mr. Mehra says. “You won’t find anything like this for children. Nothing even close.”

A CLASS THAT LOOKS NOTHING LIKE A CLASSROOM

The first session itself saw around 40 children, far more than expected. They gathered in the society garden, unsure of what was going to happen, but curious. Mr. Mehra asked a simple question:

“What is the difference between a human and a tree?”

The answers came from all directions—some thoughtful, some funny, some surprisingly deep. From there, the children moved into activities—identifying trees around them, naming small plants, and understanding shrubs, creepers, climbers, and the difference between big and small trees. Sometimes he even mixed humour into the lesson, comparing plant types to musical notes—“high, medium, low.”

“It’s unbelievable how quickly they change once the class begins,” he says. “Their eyes open in a different way.”

DRUMSTICK LEAVES AND LIGHT-SENSING TREES

One of the first plants shown to them was the drumstick (moringa). The next day, many kids returned with drumstick leaves from home, telling Mr. Mehra how it is cooked and eaten. “They were happier than usual,” he recalls, “as if they discovered something on their own.”

Children observed how leaves sense light—turning left and right, adjusting themselves to capture sunlight. This was not just information; they were actually watching it happen.

Rohit Mehra spoke to them about how trees sense wind, how roots keep working as long as they are alive, how trees do not die suddenly the way humans do, and how—even after a tree dies—everything gets reused by insects, animals, or microbes.

“Even after death, a tree continues to give,” he told them.

SIMPLE QUESTIONS BUT REAL LEARNING

The School of Trees sessions are filled with questions that sound simple but open children’s minds:

- “Who has the biggest leaf?”

- “Which tree has no seed?” (Only one Class 6 girl answered immediately.)

- “Where does water travel from inside a tree—from top to bottom or bottom to top?”

- “Soil is needed for land plants, but not for sea plants. Why?”

Some questions were playful—comparing trees and shrubs to musical notes.

These questions aren’t written anywhere. They unfold naturally as the children walk around, touch branches, look at leaves, and try to understand things they never noticed before.

ACTIVITY-BASED LEARNING

The practical work forms the heart of the School of Trees. Children learn to make seed balls, they observe sunlight falling on leaves and how leaves adjust to capture light, and they talk about organisms that live under trees.

They also brought empty plastic glasses from home, filled them with soil, put seeds in them, and watched them sprout over days. Mr. Mehra says this has become meaningful for them—”That will become their symbol, and they will get results too.”

FROM ONE SOCIETY TO A LARGER DREAM

For now, the children attending are all from Rohit Mehra’s own residential society. But interest is already growing. During a call, someone said they wanted to send their own kids for a session just to experience one such day.

In a conversation with Indian Masterminds, Mr. Mehra even discussed the possibility of expanding. He made it clear that his vision is bigger than his own garden. “My vision is for the whole of India,” he said. The idea is not limited by scale—it’s limited by resources. “For it to happen across India, resources are needed,” he admitted. “But people are accepting the concept.”

He believes strongly that schools should give two hours a week to tree education. According to him, “The formal education we take, but real education is only this.” He insists that instead of regular homework, children should be asked to take waste material from home and turn it into a plant or pot.

A UNIQUE BEGINNING

IRS Rohit Mehra further said that he also plans to invite environment-related people to speak to the children.

The School of Trees is not a big institution, not a funded program, and not even a formal school. It is just a garden, a group of children, and an officer who believes they should know trees the same way they know alphabets.

But the conversations reveal one thing clearly:

Something changes when a child finally recognises the trees around them—by name, by leaf, by seed, by light, by the creatures underneath.

And perhaps that small shift is exactly what IRS officer Rohit Mehra and his wife, Geetanjali Mehra, are trying to plant.