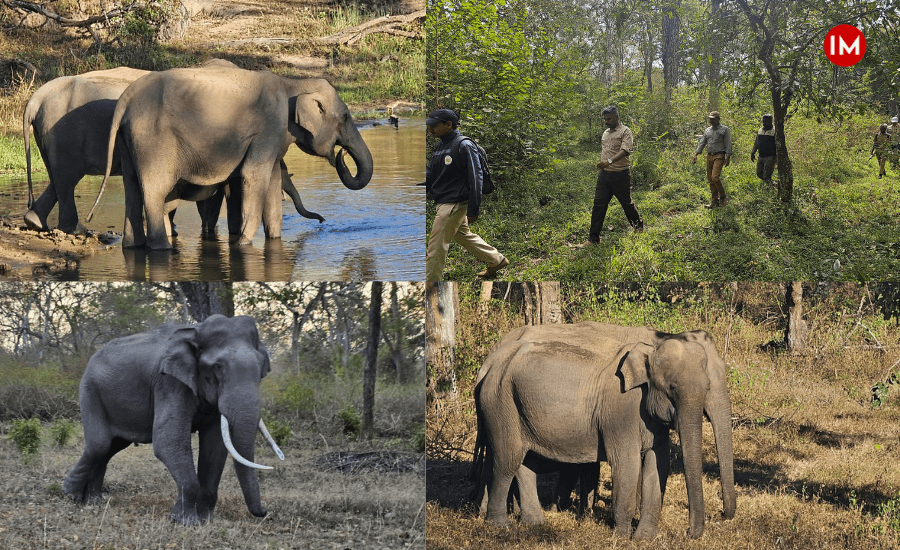

In the dense forests and sprawling landscapes of Karnataka, a meticulously planned operation unfolded from May 23, 2025. The three-day operation was supposed to count elephants – part of the third Synchronised Elephant Population Estimation Exercise across South India. It is one of the most difficult and dangerous operations since it entails sighting each elephant individually to note down its sex, age, number of members in the herd and direction of movement. Elephants might often charge towards the census party since they have to go close to the giants to count them individually. This time the operation is different because it also combines the physical sighting with camera trap sighting and DNA testing of their faeces (dung).

Coordinated by Dr Ramesh Kumar P, a 2008-batch Indian Forest Service officer and Conservator of Forests (Project Tiger) in Mysuru, this initiative covered Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh. In Karnataka, the exercise focused on key elephant habitats like Nagarahole, Bandipur, and Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple (BRT) Tiger Reserves, employing a combination of scientific methods to estimate elephant numbers and gather critical demographic data.

After a detailed conversation with Indian Masterminds, Mr Kumar shared about the intricacies of the 2025 census, the methods employed, the challenges faced, and the broader implications for elephant conservation and human-elephant conflict mitigation.

A THREE-DAY CENSUS: METHODS AND EXECUTION

The 2025 elephant census in Karnataka was a three-day endeavour, each day dedicated to a distinct method to ensure a comprehensive assessment of the elephant population. These methods—Sample Block Count, Line Transect Dung Count, and Waterhole Count—were designed to provide both direct and indirect estimates of elephant numbers while capturing demographic details such as age and sex ratios.

Sample Block Count Method

On May 23, 2025, the census began with the Sample Block Count Method, a refined version of the traditional direct count approach. This technique involves systematically surveying predefined blocks, each approximately 5 square kilometres. In Nagarahole Tiger Reserve, all 91 beats, covering over 500 hectares each, were surveyed by more than 300 staff members from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Teams of three to four observers walked crisscross or parallel patterns to cover at least 50% of each beat, recording direct sightings of elephants, including their numbers and categories (adult, sub-adult, juvenile, calf, male, female, and makhna—tuskless males). This method was also applied in adjacent plantations and estates to account for elephants outside protected areas.

To estimate the elephant population in Bandipur and BRT Tiger Reserves, forest teams used a scientific survey method called Sample Block Count. Instead of trying to count every elephant (which can be inaccurate), they focus on smaller sample areas and then scale up the data.

In Bandipur, officials surveyed 112 forest beats, with each team walking at least 15 km. In BRT, 45 teams were deployed to cover 44 beats.

During the survey, they recorded:

- The number of elephants seen in sample areas

- The size of each sample area

- The total size of the entire forest region

Using a formula by Lahiri-Choudhury (1991), they estimated the total number of elephants like this:

Estimated Elephant Population = (Elephants seen ÷ Sample Area) × Total Forest Area

To ensure the results are reliable, they also calculated the variance, standard error, and 95% confidence interval — basically, checks to make sure the final number is scientifically accurate. This method gives a more precise estimate than older counting techniques and helps in better conservation planning.

Line Transect Dung Count Method

On May 24, forest officials switched to a different method to estimate elephant numbers — the Line Transect Dung Count Method. Instead of spotting elephants directly, this approach counts dung piles to estimate how many elephants live in an area.

Here’s how it worked:

- In Nagarahole, teams surveyed 91 walking paths called transects (one in each beat).

- Bandipur used 2-kilometre transects following national tiger monitoring protocols.

- In BRT, 43 of the 54 planned transects were completed.

Each team of three had clear roles:

- One guided the path (navigator),

- One looked for dung piles (spotter),

- One measured distances from the trail (measurer).

They noted everything: location, beat name, GPS coordinates, vegetation, and even the condition of the dung piles.

Next, all this data was analysed using special software called DISTANCE, which calculated how dense the dung piles were in an area. Then, another program, GAJAHA, helped estimate the actual elephant numbers using this formula:

Elephant Density = (Dung Density × Decay Rate) ÷ Defecation Rate

Due to the absence of state-specific dung decay and defecation rate studies, default values from Varman et al. (1995) and Watve (1992) were used. This method complements direct counts by providing an independent estimate, accounting for elephants that may not be sighted during block counts.

Waterhole count method

On May 25, forest teams used the Waterhole Count Method to gather information about elephant groups — especially their age and sex. This method focused on observing elephants at water sources, salt licks, and open grasslands.

- In Nagarahole, more than 100 waterholes were monitored from morning to evening (6 a.m. to 6 p.m.).

- Bandipur covered 112 pre-selected sites and took photographs for record.

- BRT teams observed 50 waterholes across the reserve.

Observers watched quietly and carefully recorded:

- How many elephants arrived

- They looked at the elephant’s height and size to guess how old they might be:

- A calf is a baby elephant, usually less than a year old — about waist-high to an average adult human.

- A juvenile is a young elephant between 1 to 5 years old — taller than a calf but still noticeably smaller than a full-grown one.

- A sub-adult is like a teenage elephant — between 5 to 15 years old — growing fast and starting to look stronger.

- An adult is fully grown — big and tall. Females are considered adults if they’re very tall (above 7 feet), while males are even taller (closer to 8 feet or more).

To tell whether it’s a male or female, the team looked for tusks. Most males have tusks, while females usually don’t.

Some male elephants don’t grow tusks at all — these are called makhnas. They can still be identified by other signs, like a sloping back, a thicker body, or certain body features.

If the forest staff weren’t sure about an elephant’s age or gender, they simply marked it as “unidentified” to keep the data honest and accurate.

“Photographs taken during waterhole counts in Bandipur were catalogued by date and location, aiding in the identification of tuskers, makhnas, and demographic analysis. This method provides critical insights into the age and sex structure of elephant populations, essential for assessing population health and dynamics,” Mr Kumar shared with Indian Masterminds.

The 2025 Karnataka elephant census, with its blend of direct sightings, dung analysis, and waterhole observations, showcases a sophisticated approach to wildlife monitoring. These meticulously executed methods, from traversing dense forests to cataloguing photographic evidence, lay the groundwork for accurate population estimates and demographic insights. Yet, the challenges of this endeavour—ranging from monsoon-soaked terrains to the inherent risks of close encounters with elephants—reveal the complexity of counting these giants. In the next part, we explore the obstacles faced, the evolution of census techniques, and the broader implications for conservation and human-elephant coexistence.