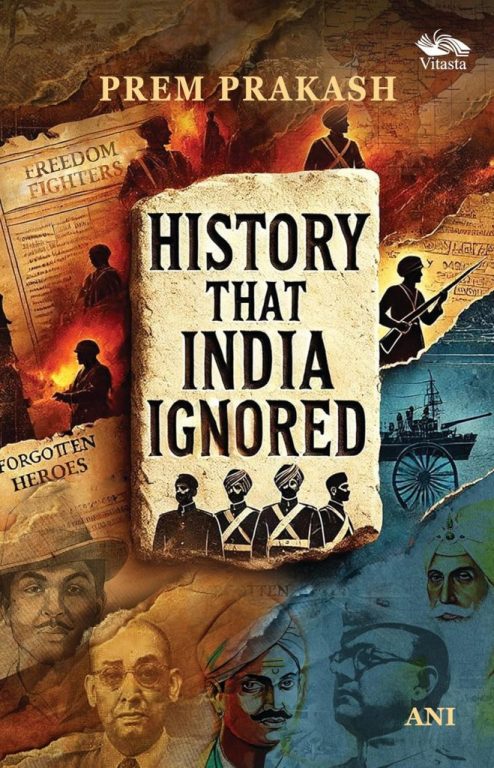

The founder and chair of the multimedia news agency ANI, nonagenarian Prem Prakash is perhaps India’s oldest working journalist and observer of contemporary affairs. He was present at Tashkent when Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri signed the Kosygin brokered peace treaty with Ayub Khan. He was absolutely prompt in responding to my request to write a few lines of endorsement for my book on Shastri under the title ‘The Great Conciliator’.

I was therefore delighted to receive a review copy of his seminal work ‘History that India Ignored’ published by Vitasta. As the book covers a very wide span of history – from the attacks of Darius in 536 BCE, and that of Alexander almost two centuries later in 327 BCE to the liberation of Goa in 1961, I decided to keep the focus on the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries – when the country was making the transition from the medieval to the modern: the terminal decline of the Mughals, the advent of the EIC, the struggle towards our freedom, and the emergence of a democratic Bharat that is India, and a union of states.

To many scholars, modern Indian history started with 1857 when the Crown replaced Bahadur Shah Zafar. The British described this as Mutiny, and even though Savarkar called this the first war of Independence when he wrote an eponymous book by that name in 1909. It took another four decades before this became part of the text book narrative. However, Prakash takes us back in time to the first uprising in Vellore in July 1806 when sepoys (both Hindu and Muslim) raised the banner of revolt against two decisions of the EIC. The first required Hindus to do away with the ‘colourings from their foreheads’, and the Muslims were asked to shave off their beards, and by the second was the supply of inferior quality uniforms. The rebellion failed because Tipu’s sons developed cold feet, but the retribution for the killing of two hundred British soldiers was absolutely brutal and meant to strike ‘awe and terror’. Over three hundred were tied to cannons and blown away in full public view, while another thousand were hunted, hounded and hanged.

However as the British conquered more territories – both by conquest, and by forcing asymmetrical treaties upon the smaller kingdoms — the racial arrogance became even more pronounced, and they learnt the wrong lessons from Vellore. Rather than accommodating the sensitivities and sensibilities of their troops by trying to know them better, they came to the conclusion that they could enforce their mandate by the exercise of brutal force, which was (perhaps) effective in the short run, but certainly counterproductive in the long durée. As such, there was a repeat of Vellore in Barrackpore in October 1824 when two regiments of the Native Light infantry, led by Bindee Tewari refused the three hundred mile long March to Chittagong with their munitions, and personal belongings on their backpacks. They were aggrieved because bullock carts had been requisitioned for their British counterparts.

This was also the time when Ranjit Singh’s Khalsa army marched victoriously to Kabul, and recovered three symbols of national pride: the gates of the Somnath temple and the Durbar Sahib (Golden Temple Amritsar) as well as the gold and jewelry from the Kashi Vishwanath Temple in Varanasi.

Thanks to Savarkar’s book on 1857, the valiant fighters against the EIC have become the stuff of legend and poems, but Prakash also throws light on the lives and sacrifices of those who came out in support of Bahadur Shah Zafar – the nominal sovereign of India — whose seal actually lent legitimacy to the actions of the EIC. One such person was the leading banker of his time – Seth Ramji Das Gurwale, who was tortured before being publicly hanged in front of the Kotwali in Chandni Chowk. His family later established the Hindu College, now rated as one of the finest colleges of the Delhi University.

After a brief lull of four decades, the banner of revolt was raised in Pune by the Chapekar brothers Damodar and Balkrishna who protested the brazen conduct of the British officers — like entry into the sanctum sanctorum of family temples and taking away of the idols with all their jewelry, under the ruse of plague control. The third brother Vasudeo then killed the informer because of whom his brothers had been arrested. All three brothers made the supreme sacrifice in the honour of their motherland.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, the land of Panchnaad (the ancient name of Punjab) was in turmoil on account of the of the provisions of the 1906 Colonisation Bill for canal colonies in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) and Montgomery (now Sahiwal) which introduced retrospective provisions regarding inheritance, homestead, sanitation, tree planting and construction norms. These were an alibi to take back the land which had been made fertile by the sweat and labour of the farmers of the Doab – the region between the Sutlej and the Beas. Two of the most popular leaders of Punjab – Lala Lajpat Rai and Ajit Singh were transported to Mandalay Jail in Burma, which was then a province of British India. While Lala Lajpat Rai returned to become the President of the INC in 1920, and founded the Servants of Peoples Society, Ajit Singh established contact with the Ghadar movement, established in the US by Indians, largely (but not exclusively) demobilized Sikhs from Punjab in the San Francisco area. Their ideologues included the legendary Lala Hardyal, Kartar Singh Sarabha, Vishnu Ganesh Pingle and Tarak Nath Das. Their strategy was to spread disaffection amongst the troops and prevent fresh recruitment to the British Indian army — their belief, unlike that of the INC and Mahatma Gandhi was that England was holding India only on the strength of the Indian army – and if they lost this strength, they would have no option but to quit. According to the author the decisive factors which led the British to leave India was not the 1942 Quit India call of Mahatma Gandhi – which had no doubt, galvanised the entire nation, but the formation of the INA by Subhas Bose and the revolt of the Indian Naval ratings which had begun to spread to RAF units across the country. It was this which broke the British resolve, notwithstanding the grand posturing by people like Winston Churchill who had proclaimed in the House of Commons in 1942 ‘I have not become the King’s first minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire’.

Prakash then tells about the INA trials held in the Red Fort and the massive outcry in the public when the three great soldiers Shah Nawaz Khan, G S Dhillon and Prem Sehgal were charged with waging war against the king contrary to section 121 of the Indian Penal Code. They were sentenced to transportation for life but sensing the general mood in the country, Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army thought it prudent to overrule the proceedings of military court martial and release all three defendants.

The last chapter in the book is about the liberation of Goa – immortalized in many ways by the popular movie Saat Hindustani in which Amitabh Bachchan makes his debut appearance. Unlike the French with whom the settlement for the return of Puducherry (formerly Pondicherry), Karaikal, Mahe, Yanam and Chandernagore was on an even keel, the Portuguese dug in their heels. They floated the concept of ‘pluricentralism’ to hold on to their estate, invoking both the Pope to protect their Catholic possessions and NATO for their treaty obligations. However, Goanese patriots like Dr Tristao de Braganza Cunha had established the movement for independence, and the Goa Congress Committee established in Bombay (now Mumbai) received the support of stalwarts like Dr Ram Manohar Lohia. When the Berlin wall came up in September 1961, NATO clarified that its treaty obligations were limited to the geographical territory of the North Atlantic. Three months later, in December 1961, Indian troops led by Gen J.N. Chaudhuri undertook a brief twenty-eight hour operation to liberate Goa.

It is true that the book is polemical for it gives us the author’s preferred version of history, but that raises an even more fundamental question: is not the mainstream version of history also a polemic? The enigma remains: can a balanced history ever be written!

One can buy book from this link – History That India Ignored