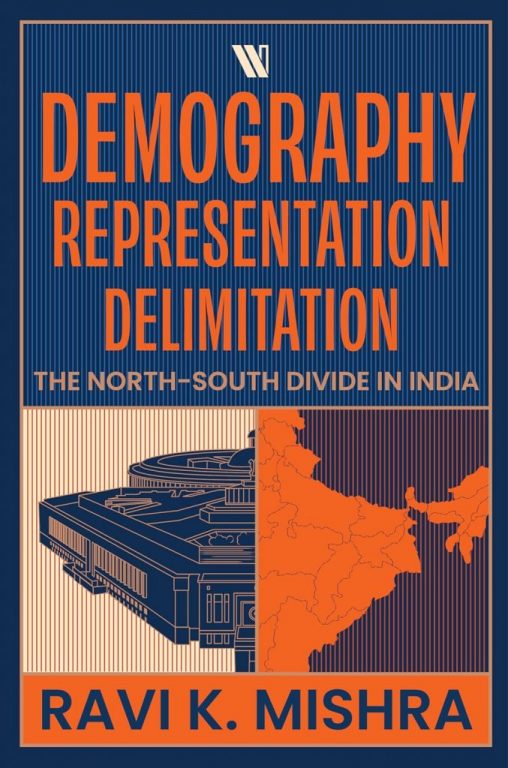

That the book is informative, engaging, provocative, and rooted ‘in the context of the contemporary’ is clear from the cover itself: the font size of Demography is bigger than that of Representation and Delimitation. The sub title of the book draws from the oft-quoted political formulation about the North South divide – as if the east and the west did not matter at all. However, As Ravi K Mishra points out, over the last century and a half – all the four regions of the country: north, south, east and west – have enjoyed phases of peak population growth lasting four to five decades, but the timings of the demographic transition in the four regions, and the states within each has been very different.

The book takes us back to the dominant construct of the seventies when the most conspicuous wall paintings, hoardings, cinema show slides and popular literature often featured the slogans: hum do, hamare do, or bus do yaa teen bachhe, lagte hain ghar mein acche. R.K. Narayan, India’s best-loved English fiction writer, set his novel The Painter of Signs in his fictional town of Malgudi. The story follows Raman, a perfectionist in painting wall hoardings, who becomes enamoured with Daisy – a well-heeled activist. She takes him under her wing as they travel through the countryside, painting slogans aimed at controlling the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of women in what was then pejoratively referred to as the ‘cow belt’ or the ‘BIMARU’ states: Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. At the time, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Uttarakhand had not yet been carved out of Bihar, MP, and UP.

Let’s now get inside this ‘dense book’ which has been described as ‘deeply researched and thought provoking’ by Shivraj Patil. Incidentally he and Somnath Chatterjee – both former Speakers of the Lok Sabha, were amongst the few politicians who spoke against the freeze on delimitation on the floor of the House, and in this, they went against the dominant position taken by their respective parties. Nripendra Mishra, the helmsman at PMML calls it an ‘evidence-based perspective on the subject of demography and delimitation’, for each statement is buttressed by figures, graphs, pie charts and tables embedded in the text, as well as appendices. For ex MP and leading columnist Swapan Dasgupta, it is ‘sensational study, which demolishes the bazaar wisdom’ and ex Sikkim Governor B.P. Singh calls it the ‘authentic study of demographic transition in Europe over centuries. C Raj Kumar, the founding VC of OP Jindal Global University puts it succinctly ‘as we draw closer to 2026 – when the fifty-year freeze on Delimitation of constituencies on account of the 42nd and 84th CSTA – this book becomes integral for policy makers and citizens alike’. They have all complimented Mishra for sifting the grain from the chaff, as well as facts from factoids – for the political discourse was based on factoids, rather than a comprehensive study of India’s demographic destiny over the long durée.

This brings us to what is contained between the covers. In addition to the Prologue, which sets the context, and the Epilogue which gives some very practical suggestions about the aftermath of lifting the fifty-year embargo and reallocation of seats in the Lok Sabha (as well as the Rajya Sabha and the state assemblies). Mishra suggests that it may be possible to give proportionate representation to each state according to the latest population data, without taking away even a single seat held at present. The book is divided into ten chapters the first three of which present an overview of the North South divide, the ‘overpopulation debate’ across India and the world with a conceptual review of the theories of demographic transition. In the overpopulation debate, we see the convergence of views of FAO, WHO, WFP, all the UN agencies as well as the Bank. This is followed by the demographic history of India during the last seven decades of the British empire, from 1872 to 1941. The next chapter is on India’s demographic divergence versus convergence, followed by a re-examination of the demographic divide between the north and the south. The correlation between demography, economic growth and urbanisation is examined in detail in the seventh chapter. A five-hundred-year perspective on demography and development places the populations of various regions in the world in perspective. At one point of time in the nineteenth century, China had 36% of the global population, but in general Indian and Chinese populations have been neck to neck. The penultimate discussion is on Indira Gandhi’s obsession with family planning, the forced vasectomy camps in the Emergency era and a critique of the excesses of that period. Finally, Mishra poses the difficult question of delimitation and seat distribution, and he builds multiple scenarios for delimitation and reallocation of seats. The last chapter compares the representation indices of the all states, and shows the current anomalies where some MPs represent less than half a million.

However, one thing is clear, arguments for and against delimitation cut across party lines. Writing in Open magazine (p. 17), Shashi Tharoor notes: ‘While there is some logic to the argument that a democracy must value all its citizens equally – whether they live in a progressive state or in one that, by failing to empower its women to reduce fertility, has allowed its population to shoot through the roof – no federal democracy can survive the perception that states would lose political clout if they developed well, while others would gain more seats in Parliament as a reward for failure.’ This is not different from what Chandrababu Naidu, or M.K. Stalin, or M.A. Baby have to say on the issue. But hold on, a former Cabinet Secretary K M Chandrashekhar has opined that ‘all south Indian states will stand to lose their political influence in comparison with the North’. Not to be left behind, the opinion from a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court reads as follows: ‘When that (delimitation happens) states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala are going to lose a large number of constituencies that they have, while states like Bihar and UP, where population is not controlled will have more constituencies. What will be the state of federalism in India? What will happen to the concept of the Union of India as was contemplated?’

A Book That Demolishes Myths Of Delimitation And Ignites Population DensityHowever, let me also state very clearly that whatever decision is finally arrived at about delimitation, it will have to be in the nature of an adjustment, a compromise – or if I could borrow the term I used for the Shastri book, something of a conciliation. India has shown how in the past, it has been able to put all doubting Thomas’s to rest about her ability to handle the difficult situations – be it the integration of the 562 odd states into the Union (Sardar Patel and VP Menon), the reorganization of states (SRC commissions), the conciliation on language (the Shastri formula), the abolition of 370, the GST regime, the Women’s Reservation Bill. We often talk of differences, but let us not forget that many of our major decisions – including the 42nd and the 84th amendments on the delimitation issue have come about on the basis of a broad consensus amongst the BJP led NDA and the Congress led UPA. What was initiated by Indira Gandhi during the Emergency was continued by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and now also – we have the solemn assurance from the Home Minister that, come what may, no state will lose out on the existing number of seats held by each state. However, having said this, there is an entire range of options – including reorganization of some of the larger states, de novo reorganization of the states of India, redrawing of the Union, State and concurrent lists, greater devolution of powers to the third tier, especially the mega cities which have a very different set of implications. While there will be a healthy debate on which option to choose, the one thing on which there will be no disagreement is that this is the book which will provide the source material for the contentious debate. This was a book whose time had come, and Ravi K Mishra stepped in with his work at the right moment. It is rare for historians to be as prescient about timing! Congratulations Ravi.