The eighth decade of the nineteenth century was epochal. Four months before the Indian National Congress was founded in December, a landmark judgment gave our eponymous ‘shero,’ Rukhmabai, the liberty not to consummate her marriage with Dadaji Bhikaji. She had argued that the marriage had taken place when she was just eleven years of age and had no agency to decide her own life. This was perhaps the first case of its kind, for the young woman in question had not only challenged the might of the imperial legal system but also the entrenched patriarchal orthodoxy of her times.

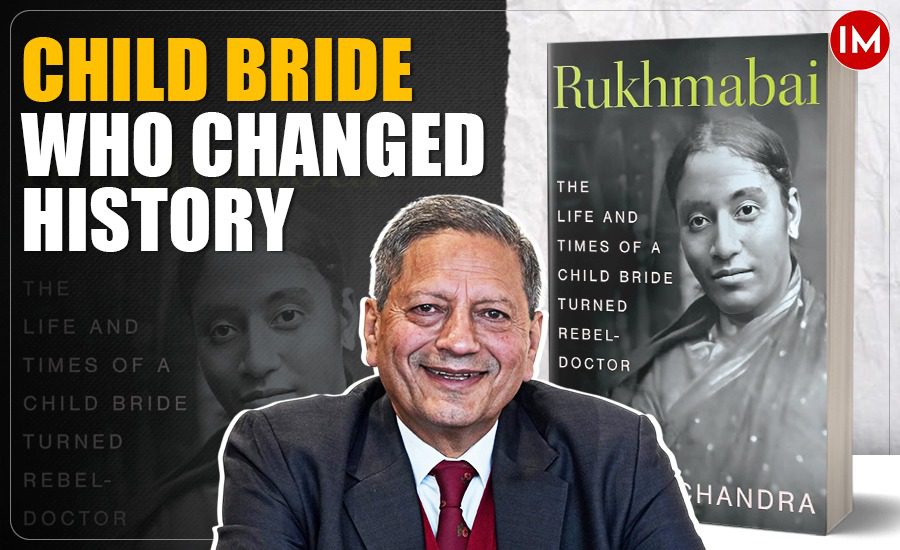

Sudhir Chandra and the resurrection of Rukhmabai

The credit for the resurrection of Rukhmabai goes entirely to the meticulous researcher, Sudhir Chandra. By happenstance, he was consulting the personal library of Dr. Sakharam Arjun, the stepfather of Rukhmabai, for his doctoral thesis on the emergence of national consciousness in India in 1968. Later in 1975, he was at the NMML (now PMML) going through the issues of Indian Spectator from January 1887 on the establishment of the Indian National Social Conference. But what held his attention was the Rukhmabai case. This had stirred a major legal debate between the Anglo-Saxon and Hindu jurisprudential canons and also divided the orthodox and progressive elements of Indian society on the contentious issue of whether marriage was a sacrament for the fulfillment of familial and religious duties or a social contract in which both consenting parties had legitimate rights and expectations. Later, he presented a paper at a seminar at IIAS Shimla and at the Women’s Study Center founded by Veena Mazumdar. Finally, in 2008, he completed his magnum opus, ‘Enslaved Daughters: Colonialism, Law, and Women’s Rights.’ Freely accessible on the Internet Archive, it provides the academic backdrop to this fascinating study.

Her inheritance: a boon or a curse?

Born in 1864, she was the only child of Jayantibai and Janardan Pandurang. Her father died when she was just two and a half. However, just before his death, Janardan had willed his entire property, valued at Rs 25,000, a princely amount for those days, to Jayantibai with her father, Harichand Yadavji (Jadowji), as the executor. However, the paternal home was not so welcoming to the mother-daughter duo, for Harichand had remarried after the death of Jayanti Bai’s mother. Six years later, at twenty-three, Jayanti was married to the thirty-four-year-old Dr. Sakharam Arjun. Rukhmabai was then eight and a half, and Jayanti’s inheritance stood transferred to her. This was also the time when the leading reformer, the thirty-one-year-old M.G. Ranade, succumbed to pressure from his family and married an eleven-year-old virgin. Virginity was a big issue—for the vagina (yoni) was either akshat (unpenetrated) or kshat yoni (penetrated). However, Ranade scores over Sakharam in that he devoted his best attention to the education of his wife, Ramabai, in spite of persistent ridicule and opposition from his family.

Back to Rukhmabai. In Dr. Sakharam Arjun, she thought she had found the father she never had. But after a brief interlude of less than three years, Sakharam decided to marry her off to a poor cousin of his, Dadai Bhikaji, who agreed to be his Ghar Jamai (a stay-at-home son-in-law), an institution that had been vehemently criticized in the 1882 Marathi feminist text ‘Stree Purush Tualana.’ Sakharam exerted no real effort to educate Rukhmabai: it was not so difficult, as he had an established practice and was in social contact with the elite, including European lady visitors. As such, there is a grain of truth in the allegations that Sakharam may have wanted to ‘retain his hold over the property.’ In fact, if Rukhmabai did not have this inheritance, why would her stepfather want a stay-at-home wastrel son-in-law? Likewise, Bhikhaji too would have easily married another wife who would have meekly submitted to his whims and fancies.

But just as Rukhmabai was determined to overcome her limitations, her husband came under the influence of his Mama (mother’s brother), who was a petty contractor with a mean mind. So, as she was evolving into a cultivated person, her obnoxious fiancé was descending to the lowest step in the social ladder. In fact, by 1882, when she was entering her twentieth year, she joined the Bombay branch of the Arya Mahila Samaj as its secretary and attended the weekly lectures on a range of subjects.

Around this time, Bombay got an exceptionally liberal governor in Lord Reay. His wife started organizing zenana parties to which ‘Sakharam’s daughter’ was regularly invited, thereby putting her in touch with two of her earliest benefactors, Nora Scot and Dr. Edith Pechey. By now, she was also writing regularly to the Times of India as ‘a Hindu lady.’ Early marriage prevented girls from any avenue of higher education. In one of her letters, she wrote, ‘For she is generally a mother before she is fourteen, when she must, out of necessity, give up the dream of mental cultivation and face the hard realities of life. It seems, therefore, hopeless to expect any advancement in higher female education when the custom of infant, or rather early, marriage continues as rife as before.

Bhikaji versus Rukhmabai—a landmark case

As Rukhmabai was postponing the consummation of marriage for one good reason or the other, Dadaji Bhikaji – and more than him, his sinister uncle Narayan Dhurjati—sought legal recourse to compel Rukhmabai to cohabit with him. Eminent barristers were now engaged by both sides. Messrs. Chalk and Walker were on the side of the plaintiff, Bhikhaji, while Messrs. Payne, Gilbert, and Sayani were on the side of Rukhmabai, the defendant. Even though Sakharam died in April 1885, she found support in Jadowji, her maternal grandfather; Behramji Malabari, the erudite and forceful editor of Indian Spectator; Henry Curwen, the celebrated editor of Times of India; and the Advocate General of Bombay, F.L. Latham. When the case came up on 19 September 1885 before Justice Pinhey, he dismissed it outright, stating that ‘it would be a barbarous, a cruel, a revolting thing to do to … when the plaintiff found that the young lady was unwilling to share his home, he should not have tried to recover her person as if she had been a horse or a bullock.’

While the decision was celebrated in the Times of India (Bombay), the Statesman (Calcutta), and the Civil and Military Gazette (Lahore), and the redoubtable London Times wrote eloquent columns, the Hindu orthodoxy was quick to take deep offense. These included Tilak’s Maratha in Pune and Mandalik’s Native Opinion in Bombay. Two years later, the case came up before the division bench of the Bombay High Court, but Rukhmabai stumped all present by stating that rather than accept cohabitation against her will, she would willingly undergo the six-month punishment that the court could impose upon her! So, in more ways than one, she was the original Satyagrahi! Finally, after a year’s procrastination, a compromise was arrived at between the litigants when, on a payment of Rs 2000 by Rukhmabai to Bhikaji, he undertook ‘not in any way to execute the decree, nor in future to assert any claim by suit or otherwise as a husband against the defendant’s person, or her present or future estate.’

The next decision of her life was equally, if not bolder. She decided to move beyond the shores of India to pursue medical education in England. Thanks to the mentorship and advice of her mentor, Dr. Edith Pechey, who gave her a copy of Medical Women—the story of the brave ‘Edinburgh Seven,’ the first ones to complete medical education in England. Pechey convinced the Rukhmabai Defence Committee to give her passage money to go to England to pursue her medical studies there. Somewhat similar to the promises made by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to abjure beef, liquor, Englishwomen, and Christianity, Rukhmabai’s mother insisted on the same, but she showed greater pluck than Mahatma by not accepting the dietary restriction to beef.

The next six years were spent in England—she lived with some of the most distinguished liberals of England, who were pressing for universal suffrage, workers’ rights, and universal access to public health and education. Travelling through the UK, she learned that all of it was not England: the Scots, the Irish, and the Welsh had their distinct identities. Every term in the medical school began with an inaugural lecture—Dr. Florence Nightingale Boyd, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, Dr. Mary Emily Dowson, and Dr. Helen Webb were some of the distinguished luminaries who inspired her to have ‘an awakened social conscience that was both dignified and reflective’ and to realize that individual well-being was inseparable from collective well-being.

Returning to Bombay in January 1895, she first worked at the Cama Hospital before joining Surat as the head of the Sheth Morarbhai Vijbhukhandas Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children. It was here, finally, at the age of thirty, she set up her own home–her castle–where she entertained her friends and some of her step-siblings, nephews, and nieces. She was fully involved in the efforts to control the infamous Surat plague of 1897, for which she was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Silver Medal, and had the privilege of receiving the first lady of India, the Vicereine, Lady Elgin, at her Zenana hospital. She found acceptance both in the havelis of the merchants and the local club, where she played tennis with the district collector. In fact, when the Congress session was held at Surat in 1907, she attended the All-India Women’s Conference for her old friend and associate Ramabai Ranade, who was presiding over the session. Yet, in 1917, she had to leave Surat for Rajkot after twenty years, as rising funds and subscriptions for the expansion of the hospital were becoming a real strain.

Her penultimate professional assignment was at the Rasulkahnji Zenana hospital in Rajkot, which had been established by the Kathiawar States Agency. It is said that the Maharani of Palitana offered her own palace and tennis courts to motivate her to take this assignment. But the hauteur of these princelings was not easily broken, and she preferred the tennis courts of the eminent lawyer Sitaram Narayan Pandit, with whom she enjoyed a good intellectual rapport. After thirteen years in Rajkot, she came back to her own city of Bombay to join the King Edward Memorial Hospital and Seth Gordhandas Sundardas Medical College for the last four years of her professional career. She chose the ‘vanaprastha,’ and for the next twenty-six years, she led a sequestered life, avoiding any public contact or engagement, thereby adding to the enigma and difficulty of understanding the innermost thoughts of this child bride turned rebel doctor.