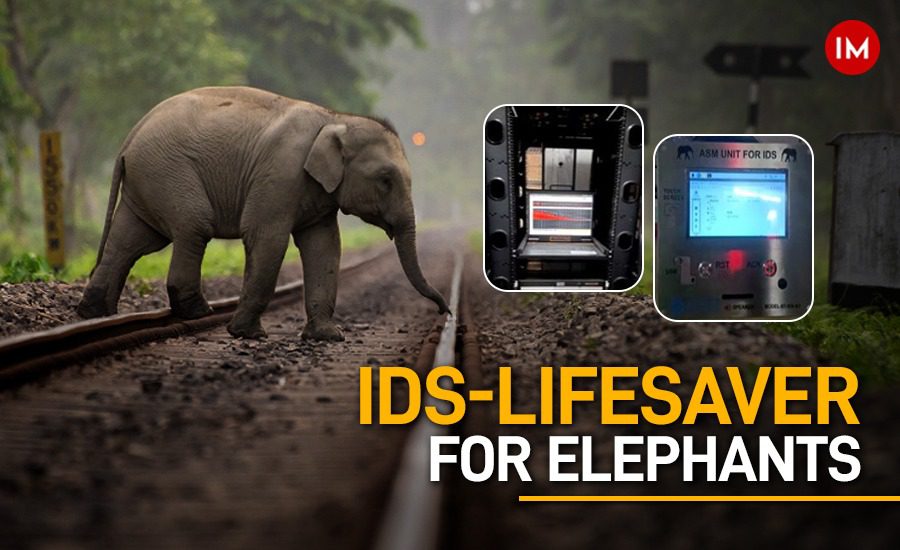

In the dense forests and tea estates of North Bengal, railway tracks cut through age-old elephant corridors. For decades, this overlap between wildlife movement and fast-moving trains has led to tragic consequences. Now, along the vulnerable stretch near Binnaguri Railway Station in Jalpaiguri, a quiet technological revolution is attempting to change that story.

The Ministry of Railways, working in coordination with the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, has introduced an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) – a fibre-based monitoring mechanism designed to detect elephant movement near railway tracks and alert authorities in real time. What began as a pilot project in one of the most sensitive corridors under the Northeast Frontier Railway is now being expanded across the country.

Indian Masterminds interacted with 2013 batch Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer Vikas V, Divisional Forest Officer (DFO), Jalpaiguri, along with senior officials from the Northeast Frontier Railway, to understand the Intrusion Detection System, its functioning on the Binnaguri stretch, and its impact on preventing train-elephant collisions.

Where the Risk Was Real

Binnaguri falls in the 52-km Madarihat–Nagrakata section – one of the most vulnerable elephant corridors along railway lines in India. Herds regularly cross this stretch while moving between forest patches. In the past, collisions were frequent and devastating.

National data underscores the urgency. Between 2019-20 and 2023-24, 81 elephant deaths due to train collisions were reported across states. In the last five years, railways have recorded an average of around 16 such incidents annually. The rising toll made it clear that traditional measures alone were not enough.

It was in this context that the IDS was introduced here as a pilot.

Inside the Control Room at Binnaguri

Step inside the control room at Binnaguri Railway Station and the system’s importance becomes immediately evident. A detection panel constantly monitors signals coming from optical fibre cables laid beneath the ground.

The fibres are installed nearly 20 metres away from the railway track and about three feet below the surface. Coiled in a specific pattern, they are designed to sense vibrations generated by heavy animal movement. The technology works on Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS), where laser pulses travel through the fibre and return signals are analysed. Any disturbance — such as the weight and pressure of an elephant – alters the vibration signature. If the pattern matches a pre-fed profile, an alarm is triggered instantly.

When that alarm goes off, the station master acts without delay. If a train is approaching or already in motion, the loco pilot is immediately informed through walkie-talkie. The train’s speed is reduced to around 25 kmph, the horn is sounded continuously, and the train proceeds cautiously through the stretch.

An officer at the station explains, “We get alerts almost every day. The moment detection happens, the information reaches the monitoring system at Binnaguri. If a train is moving, the loco pilot is informed immediately. After that, trains move very slowly on that stretch and use the horn continuously. The idea is simple – prevent a collision before it happens.”

Nearly 20 trains pass through this section daily, and the hours between 5 pm and 9 pm are considered particularly sensitive.

Why Early Detection Matters

Railway officials say elephants behave differently from other animals when confronted with an approaching train.

“Other animals disperse quickly when the horn is sounded,” a railway official explains. “Elephants, because of their size, find it difficult to climb down the slope beside the track. They often run along the track because it is easier. Even if the loco pilot applies brakes, the stopping distance may not be enough.”

This behavioural pattern makes early detection – well before the train reaches the animal – crucial.

What the Forest Department Says

For the Forest Department, the IDS is part of a broader conservation effort.

IFS Vikas says the system is currently operational on a small but critical stretch around Binnaguri, particularly in the G-CORE elephant corridor.

“It’s on a limited stretch right now,” he explains. “But after installation, there has not been any unfortunate incident on that particular section. Earlier, such incidents used to occur. On this stretch, we have not seen damage after the system was put in place.”

He clarifies that the alert is received at the monitoring system inside Binnaguri Railway Station. “If an elephant crosses the railway line and the system detects it, the station master immediately informs the loco pilot. Even if the train is already passing, they reduce speed and move cautiously. That is how the system functions.”

The Forest Department also runs a Railway-Forest Monitoring Group. Field staff post real-time updates about elephant movement – even specifying pillar numbers where herds are spotted. This information is shared instantly with railway authorities, who can impose temporary speed restrictions.

“We give the Railways data about major crossing points,” IFS Vikas says. “Coordination is key. Whether it is speed restriction, underpass construction or additional monitoring, we discuss everything together.”

Is It Fully AI-Enabled?

Although described as AI-enabled, officials acknowledge that full AI integration is still under development.

“At present, the optical fibre cables detect heavy-weight movement within about 10 to 15 metres of the track,” Mr Vikas explains. “It is not fully linked to AI yet. Any heavy animal can trigger an alert. We are in the process of calibration.”

Future plans involve pattern detection – analysing footprint size, weight impact and vibration signatures to distinguish elephants from cattle, vehicles or other heavy disturbances.

“When AI is integrated,” he says, “we will be able to identify exactly which animal is passing. That will make the system even more effective.”

A meeting was recently held in Alipurduar to review the system’s performance. A detailed report on its efficacy is being finalised. Expansion to cover the entire vulnerable stretch is already in process, with tenders floated and phased implementation planned.

Scaling Up Across India

Encouraged by the pilot’s performance, the Ministry of Railways has sanctioned installation of IDS across 1,158 route kilometres spanning eight railway zones, including Northeast Frontier Railway and several others across the country. Currently, 141 route kilometres are operational under NFR, with further expansion planned by April 2026.

In parallel, a national study identified 127 vulnerable railway stretches covering 3,452.4 km. Of these, 77 stretches across 14 states have been prioritised for mitigation.

A Multi-Layered Approach to Protection

The IDS is not a standalone solution. Railways and forest authorities are also implementing several additional measures – imposing speed restrictions at identified locations, constructing underpasses and ramps, installing fencing and signage boards, clearing vegetation near tracks, deploying elephant trackers, installing honey bee buzzer devices as repellents, and experimenting with thermal vision cameras for night detection.

In case of any collision, Zonal Railways conduct joint investigations with the Forest Department and take immediate corrective steps.

A System Still Evolving

For now, the stretch near Binnaguri stands as a testing ground where conservation and technology intersect.

“What has been installed is preliminary,” Mr Vikas says candidly. “We are studying its effectiveness. With better calibration and AI linkage, it will improve further.”

In a landscape where steel rails meet ancient migratory paths, the Intrusion Detection System represents more than a technological experiment. It is an attempt to ensure that development does not come at the cost of India’s largest land mammal – and that, on these forested tracks, both trains and elephants can pass safely.

Read Also: How Railways’ Intrusion Detection System Works to Avert Train-Elephant Collisions