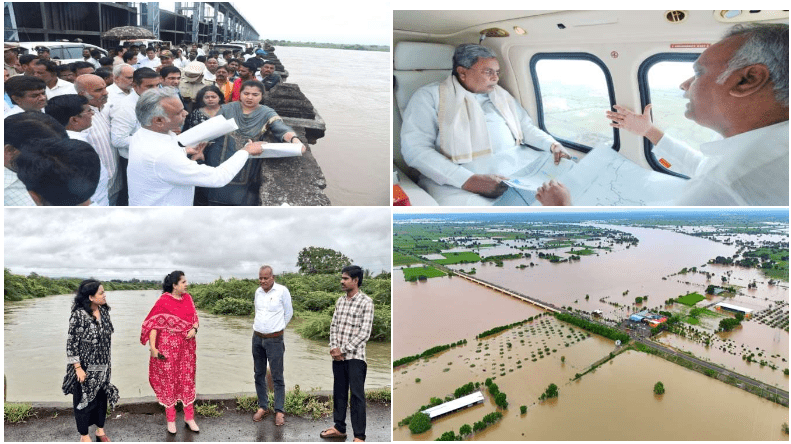

When the monsoon clouds settled over Kalaburagi in late 2025, they brought more than just rain. They carried weeks of uncertainty. Streets turned into streams, fields vanished underwater, and entire villages watched the rivers rise inch by inch. What unfolded was one of the district’s toughest battles in recent memory — a battle against floods that tested its people, its administration, and its resilience.

A FLOOD LIKE NEVER BEFORE

Kalaburagi’s troubles began when relentless rain—much of it flowing from Maharashtra—forced major reservoirs, including Ujani, to release large volumes of water. The Bhima River rose first. Then the Kagina and Amarja followed. Local streams spilled over. One by one, villages across Afzalpur, Jewargi, Chittapur, Sedam, Aland, Kalagi, Shahabad, and Chincholi went under water.

Bridges disappeared. Roads broke apart. Even National Highway 50 faced major disruptions. Families climbed to rooftops and upper floors, hoping rescue teams would reach them.

“It was clear that this was not a routine flood,” recalls Fouzia Taranum, IAS (Karnataka Cadre, 2015), Deputy Commissioner and President of the District Disaster Management Authority. “The rivers were moving faster than we had ever seen.”

THE PEOPLE WHO LOST EVERYTHING

Across the district, homes, farmlands, and livestock were destroyed. Paddy, cotton, sugarcane, pulses, and tur fields vanished under sheets of brown water. Crops for the next cycle were also lost. For many farmers, this was nothing short of disaster.

Schools shut down for weeks. Electricity lines collapsed. Drinking water supply broke down in several pockets. Families who had never left their villages were suddenly sitting in crowded relief halls, unsure of what would come next.

By the end of the worst phase, 51,281 people had been moved to 56 relief centres.

Read More : How a Millet Rotti Became Kalaburagi’s Global Brand

A DISTRICT ON EMERGENCY MODE

The district administration had already placed nodal officers in flood-prone pockets before the rains peaked. When the water began rising fast, these teams swung into action. SDRF units, local police, volunteers, and boat teams moved through submerged lanes to rescue stranded villagers.

Food, water cans, medicines, and blankets were delivered to shelters around the clock. Livestock shelters were set up on higher ground. Medical teams visited relief centres daily to check for infections and waterborne diseases.

“We had to move fast,” says Taranum. “In a disaster, every hour decides the outcome. Our only focus was saving people and stabilising the situation.”

HELP WHEN IT MATTERED MOST

Relief measures continued even as rains eased. The Karnataka government, after an aerial survey, announced additional compensation for farmers—higher than national norms—for dry land, irrigated crops, and perennial crops. Joint teams assessed village damage, listed repair needs, and submitted reports for long-term rehabilitation.

Strict warnings were issued across all taluks. No swimming. No grazing animals near riverbanks. No washing clothes, fishing, or taking photographs close to flooded streams. The administration wanted zero casualties from risk-taking.

Emergency helplines—district-level and taluk-level—were kept active day and night. Calls poured in from Aland, Shahabad, Yadrami, Jevargi, Chincholi, Afzalpur, Sedam, and Kalaburagi itself.

COMMUNITIES THAT STOOD TOGETHER

Youth groups, NGOs, women’s collectives, and local religious institutions filled key gaps. They cooked meals, transported relief materials, and helped families locate missing members. Volunteers guided elderly people and children during evacuations.

The administration calls this the backbone of Kalaburagi’s resilience. “Government machinery alone cannot fight a disaster of this scale,” Taranum says. “The people of Kalaburagi stood by each other. That made the difference.”

AFTER THE WATER RECEDED

When the rivers finally withdrew, a new challenge began. Silt covered agricultural land. Culverts and roads needed rebuilding. Power lines had to be restored. Many houses required full reconstruction. Health teams continued monitoring for infections.

Experts pushed for long-term solutions—desilting rivers, building better drainage, enforcing planning norms, removing encroachments, and strengthening flood barriers. The administration agreed that the district could not afford a repeat.

A MODEL FOR DISASTER MANAGEMENT

The Karnataka Disaster Management Authority later praised Kalaburagi’s response as one of the state’s finest examples of coordinated disaster management. Much of the credit went to the preparedness, teamwork, community spirit, and communication sustained during the crisis.

For Taranum, the flood remains a lesson in leadership and humility. “A disaster tests not just systems but compassion,” she says. “Our duty is to protect every life—no matter how difficult the circumstances.”

A DISTRICT THAT REFUSED TO GIVE UP

The 2025–26 floods will be remembered for their destruction. But they will also be remembered for the courage shown by thousands—farmers, families, officials, youth volunteers, and rescue teams.

Kalaburagi did not just endure the flood. It fought back, side by side, step by step.

And it emerged stronger.