Ujjain’s identity has always been spiritual, defined by the Shipra, ancient temples, and the Simhastha Kumbh Mela that draws millions every twelve years. Yet behind its religious prominence lay an uncomfortable ecological truth.

The district spans nearly 6,000 square kilometres, but forest cover stood at just 0.69 per cent, around 40 square kilometres. In a city preparing to host 30–40 crore pilgrims during the Simhastha 2028, the absence of green buffers, shaded corridors, and natural cooling zones was not just an environmental concern, it was an urban risk.

When Kiran Bisen, 2009-batch IFS officer of the Madhya Pradesh cadre, took charge, she saw what most people had accepted as permanent. Open land lay neglected. Riverbanks stood exposed. Hillocks became dumping grounds. Forests, in a city that worships nature, barely existed.

“People assume forests only belong far away, in reserves. But cities also need forests, otherwise they stop breathing,” she shared with Indian Masterminds.

FROM SCATTERED PATCHES TO A CITYWIDE PLAN

There was no grand budget waiting. No large forest blocks ready to be notified. What existed were revenue lands, unused institutional plots, roadside stretches, temple precincts, riverbanks, and abandoned hillocks… spaces dismissed as unimportant.

Instead of waiting for perfect conditions, Bisen began mapping what was already there.

At least two riverside zones along the Shipra, university campuses, unused temple-adjacent land, road medians, and vacant government plots were identified. The approach was simple but deliberate: ‘wherever land was idle, forests would grow’.

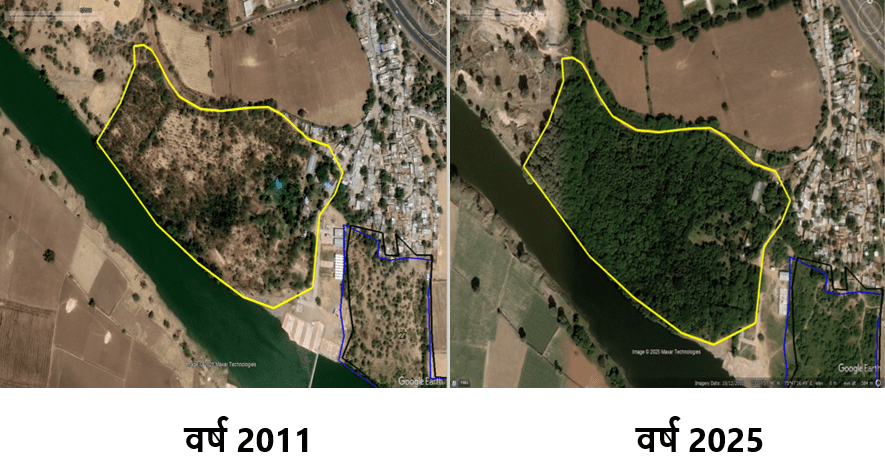

Plantation drives began along the Shipra’s banks. Over time, nearly two lakh saplings were planted along the river, creating shaded stretches where none existed before.

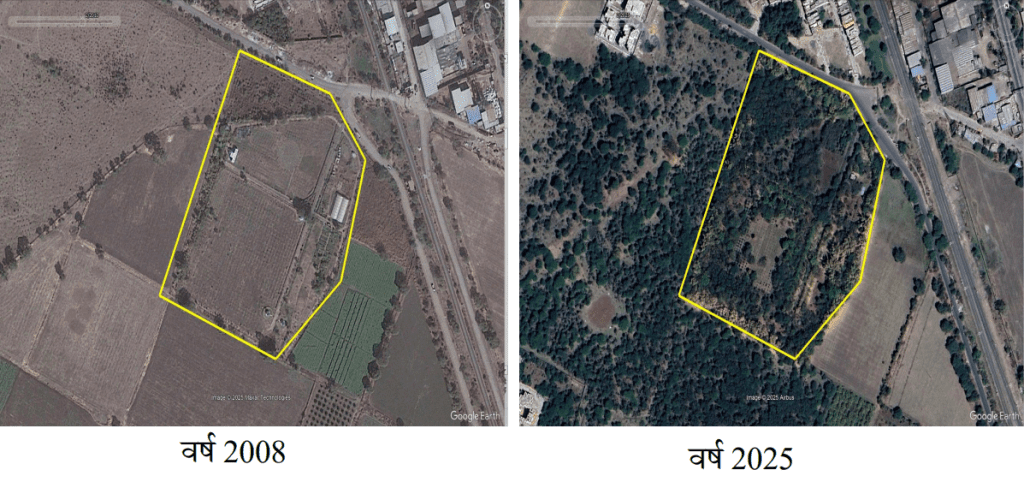

Satellite images later revealed the change. Areas once brown now showed clear green signatures.

SANSKRITI VAN: A FOREST RISES INSIDE A UNIVERSITY

One of the most defining interventions came when Vikram University handed over 11 hectares of land that had remained unused for years.

Instead of turning it into a garden or fenced plantation, Bisen envisioned a dense, immersive forest, one that reflected the cultural roots of the city itself.

The result was Sanskriti Van.

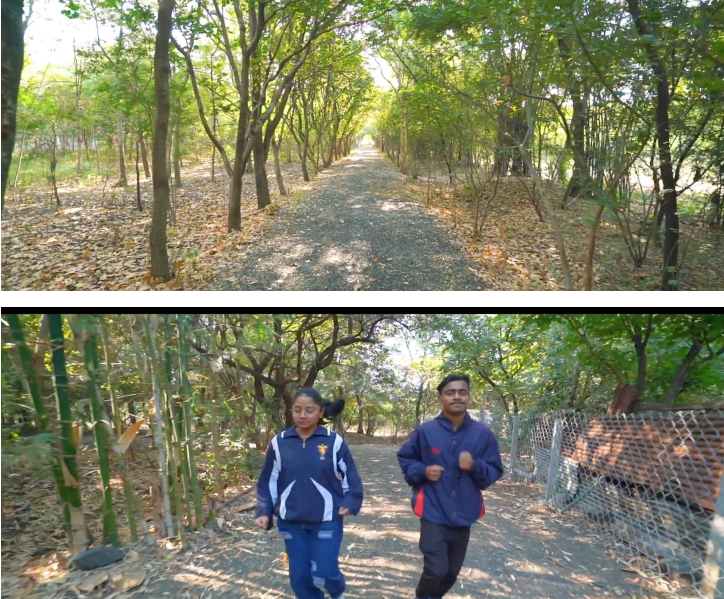

The land was transformed into a full forest ecosystem, planted with native species. Today, it stands not just as green cover but as an educational and cultural space, used by students, walkers, and researchers alike.

“This land was waiting,” Bisen recalls. “Once institutions trust the idea, forests grow faster than we imagine.”

RECLAIMING HILLOCKS, RIVER EDGES, AND NEGLECTED CORNERS

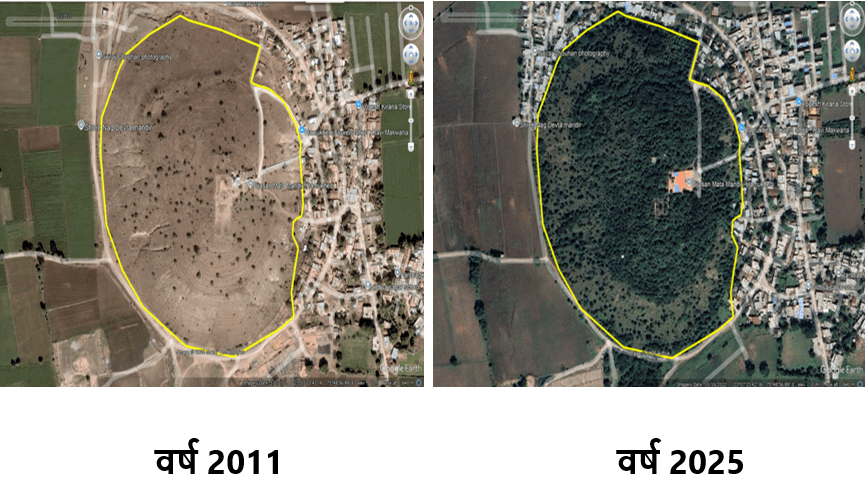

Across Ujjain, several spaces had become informal dumping grounds or spots for anti-social activity such as small hillocks near temples, vacant land parcels, and river-adjacent stretches.

These were systematically reclaimed.

- Jasan Tekdi was converted into a forested hill.

- Chamunda Mata Van emerged on temple-adjacent land.

- Along the Shipra near Khairagarh, a Miyawaki plantation transformed nearly 20 hectares into dense green cover within a short span.

Before-and-after visuals tell the story clearly: barren land replaced by layered vegetation, visible even on satellite imagery.

NAGAR VANS AND PEOPLE WHO BELONG TO THEM

Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of Bisen’s work was how forests were made personal.

Through Nagar Vans, citizens were invited to plant trees to mark birthdays, anniversaries, or memories of loved ones. These forests did not remain government property in people’s minds; they became shared spaces.

“Once people plant a tree for something personal, they return to see it,” she explains. “That’s how habits form.”

Schemes like Ankur Abhiyan, local drives, and community partnerships strengthened this bond. The goal was not only plantation, but continuity.

A CHANDAN VAN FOR FAITH AND FARMERS

Understanding Ujjain’s religious landscape, Bisen introduced something rarely attempted in urban forestry: a Chandan Van.

A two-hectare demonstration plot was developed to showcase sandalwood cultivation. Farmers were encouraged to adopt sandalwood in their own fields, linking ecology with livelihoods.

Temple institutions and religious bodies were involved, grounding environmental work in the city’s belief systems.

YOUTH, CAMPS, AND A SENSE OF OWNERSHIP

Young people became central to the effort.

Through nature experience programmes, camps, and guided visits at places like Lakshmi Nagar and Manoranjan Park, youth were introduced to forests not as abstract ideas but lived spaces.

Picnics, walks, and hands-on activities helped build a connection that extended beyond official campaigns.

“What stays with them is the experience. Once that happens, protection comes naturally,” she told Indian Masterminds.

WHAT CHANGED ON THE GROUND

Five years after early plantations, the difference became visible, without waiting for formal studies.

- Bird species returned, including peacocks.

- Dense patches showed lower ambient temperatures, often by two degrees, compared to surrounding concrete zones.

- Soil quality improved; university students began studying soil microbes.

- Areas near forests felt cooler, cleaner, and calmer.

“Earlier, these places looked like open fields,” she notes. “Now you can tell immediately where the forest begins.”

Groundwater recharge and reduced surface pollution near riverbanks were observed, though long-term data is still being compiled.

FAITH, RIVERS, AND THE QUESTION OF POLLUTION

In temple cities, river pollution is often blamed on religious practices. Bisen addresses this directly.

During her tenure, she found no direct discharge of temple offerings into the Shipra from major sources like the Mahakal temple. Systems existed where offerings were diverted underground, not into the river.

“Many assumptions circulate,” she says. “But during my time, I did not find direct temple discharge into the Shipra.”

Instead, plantation along riverbanks played a visible role in filtering runoff and improving river-edge conditions.

ADMINISTRATION, COORDINATION, AND UNUSED LAND

Surprisingly, major administrative resistance was minimal.

Revenue land was officially handed over. Religious institutions cooperated. The Collector and Commissioner remained supportive. Even industrial units were brought into the process.

Cement factories were directed to develop green belts. Hospitals contributed funds for plantations. Public sector units and NGOs were involved through compliance and collaboration.

“When forests are not notified, budgets are limited,” Bisen explains. “So coordination becomes essential.”

GROWTH NEEDS GREEN SPACE

With highways expanding, lanes doubling, and construction accelerating, Bisen believes green cover must grow alongside infrastructure.

“If roads increase, green areas must also increase,” she says. “That balance decides whether cities remain livable.”

As Simhastha 2028 approaches, Ujjain’s new forests may not dominate headlines, but they will quietly support millions who walk its streets, rest under its trees, and gather along its river.

In a city once defined by temples alone, forests have begun to claim their space again, not on the outskirts, but right where people live.