Although India is home to around nine different species of vultures, due to a rapid and major population collapse in recent decades, most of these vultures are now facing the danger of extinction. The dramatic vulture decline observed across India presents a range of ecological threats, by influencing the numbers and distribution of other scavenging species as well.

Numerous conservation schemes are in place to assist in the recovery of the vulture population and their protection & conservation. One of India’s biggest natural parks, the Panna Tiger Reserve (PTR) of Madhya Pradesh is also walking in the same footsteps.

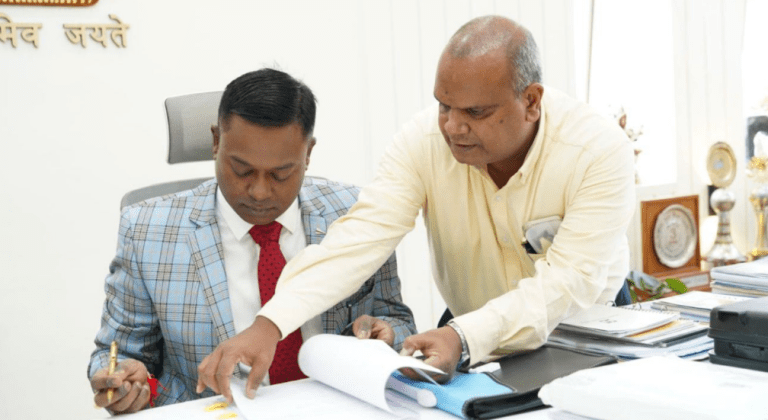

In an exclusive conversation with Indian Masterminds, on the occasion of International Vulture Awareness Day, Field Director of Panna Tiger Reserve, Uttam Sharma, IFS, shared details about their attempts at saving and conserving the critically endangered bird.

THE VULTURES OF PANNA

According to the officer, about 650 vultures of six species were reported in the tiger reserve in the year 2018. Out of these, four were resident species while three were migratory.

Out of the nine vulture species found in the country – Oriental White-backed Vulture, Long-billed Vulture, Egyptian Vulture, Indian Griffon Vulture, Himalayan Griffon, Cinereous Vulture, Slender-billed Vulture, Red Headed Vulture, and Bearded Vulture or Lammergeier – the first six are found in the Panna Tiger Reserve, including the endangered White-backed Vulture and Long-billed Vulture.

GEO TAGGING VULTURES

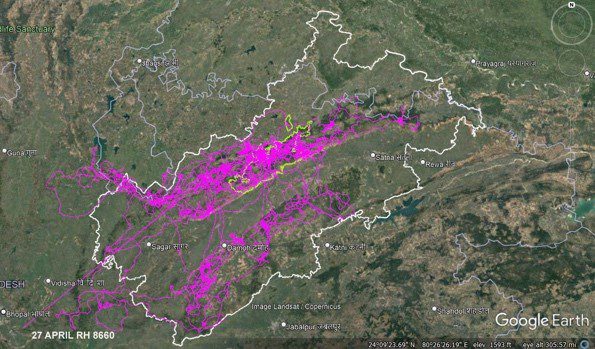

In order to study the movements and habits of the scavenger birds, the Panna Tiger Reserve came up with the decision of radio tagging the vultures of the park. Since the catastrophic decline in their population in the past few years, telemetry-based research has become imperative for understanding the movement pattern of these birds. This includes migration, foraging, roosting, nesting, bathing, and other behaviors, understanding all of which is critical for their conservation.

The vultures are tagged with a GPS device as part of a scientific exercise to monitor vulture movement for understanding the behavior of the species in the protected area of Madhya Pradesh. They were tagged with sophisticated GPS tags, known as e-ObsTags. The tags, manufactured in Germany, are solar-powered and weigh between 25 g and 75 g, which is quite light in weight compared to the birds that weigh over 12 kg.

“So far, we have radio-tagged 25 vultures which includes 13 Indian vultures, 8 Himalayan griffon vultures, 2 Eurasian griffon vultures, and 2 king vultures (redhead vultures). Out of these four species, the Himalayan and Eurasian Griffon vultures are of migratory species, and the other two are resident species,” Mr. Sharma shared with Indian Masterminds.

HOW IS IT DONE?

In order to tag the vultures, they need to be captured for a while. These vultures were captured based on different methods that include a walk-in enclosure (placing a piece of meat in a cage and waiting for the bird to enter and eat it and capture it in the process), a leg-hold trap, and a claptrap. These were well-established traditional methods that were successful in catching hold of the large bird.

The vulture tagging was carried out by a team, including veterinarians from the Wildlife Institute of India under the Landscape Management Plan project, supported by professional trappers, resident veterinary officers, and park officials of PTR.

The process involved multiple stages such as preparation, capturing, tagging, measuring, and releasing. Every day, the team would reach the field before sunrise, set up traps, and wait for the birds. Once the birds were captured, they had to be handled carefully, owing to their size and fragility. Thus, professional help was required at all times.

Once they were successfully captured, the birds were tagged with the GPS device. The tags were configured to collect and store data and then transmit the data whenever they come in the transmission link. The data is transmitted when the birds take flight and soar. Moreover, it collects data every five minutes, allowing fine-scale data along with elevation, temperature, and activity.

TRACKING THEIR PATHS

Since tagging involved both resident and migratory birds, the project gave insight to conservationists and researchers about the birds’ movement patterns, in and out of the country. Like a smartwatch, the tags share minute-to-minute details about the birds’ whereabouts, activities, eating/drinking patterns, resting schedules, feeding, roosting, etc. with them. This information in turn helps the team plan conservation and protection interventions in the locations where the vultures face threats.

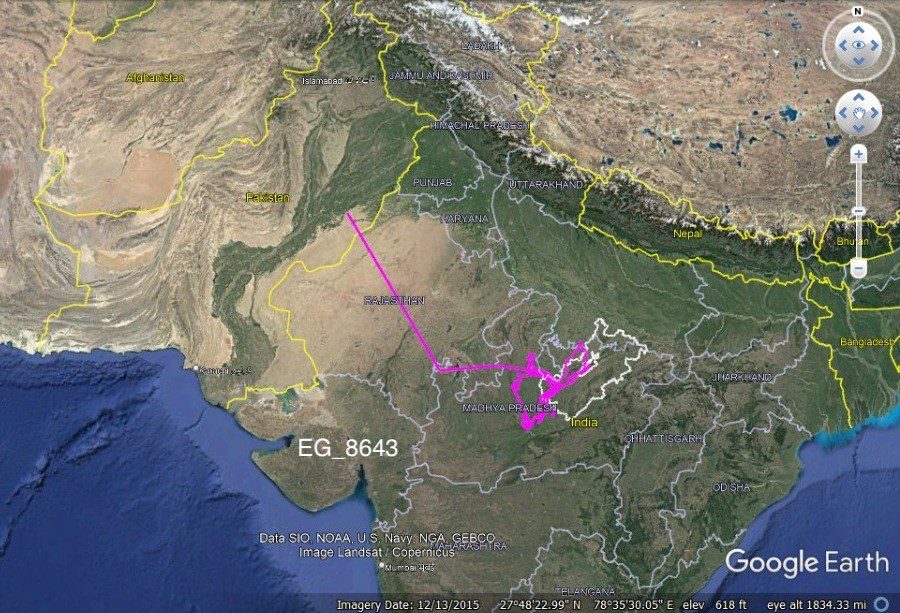

“We tagged the migratory birds in February, and around April, they started their return journeys back to their countries. From April onwards, we have been receiving data on their movement in different countries. They went from Nepal to Tibet, followed by China. Similarly, on the western side, the European griffon went via Rajasthan to Pakistan followed by Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. They are staying in those regions right now,” Mr. Sharma said.

He added that they hope that the birds will return back to Panna Tiger Reserve in the months of October and November. “It will be interesting to see how many birds come back to the reserve.”

BENEFICIAL IN THE LONG RUN

The data and statistics provided by the tagging will help the conservationists in establishing baseline data of these activities across a comprehensive scale. Furthermore, pathological, and microbiological analysis from the derived samples will help them in determining the overall health status of individual birds and to a certain extent, the health of vulture populations in and around the reserve.

All the data collected from the current study will ultimately lead to significant policy implications in providing answers to existing knowledge gaps, and towards adaptive management of these raptors in the Panna Tiger Reserve.