Recently, troubling news emerged from Chhattisgarh – in the past four years, 37 herds comprising nearly 350 wild elephants have been responsible for the deaths of over 250 people across the state. The satellite-based monitoring system (Caller ID), once used to track elephant movements, had collapsed two years ago. To fill the gap, the forest department set up an Elephant Monitoring Cell at the Jungle Safari – but even that has failed to function effectively.

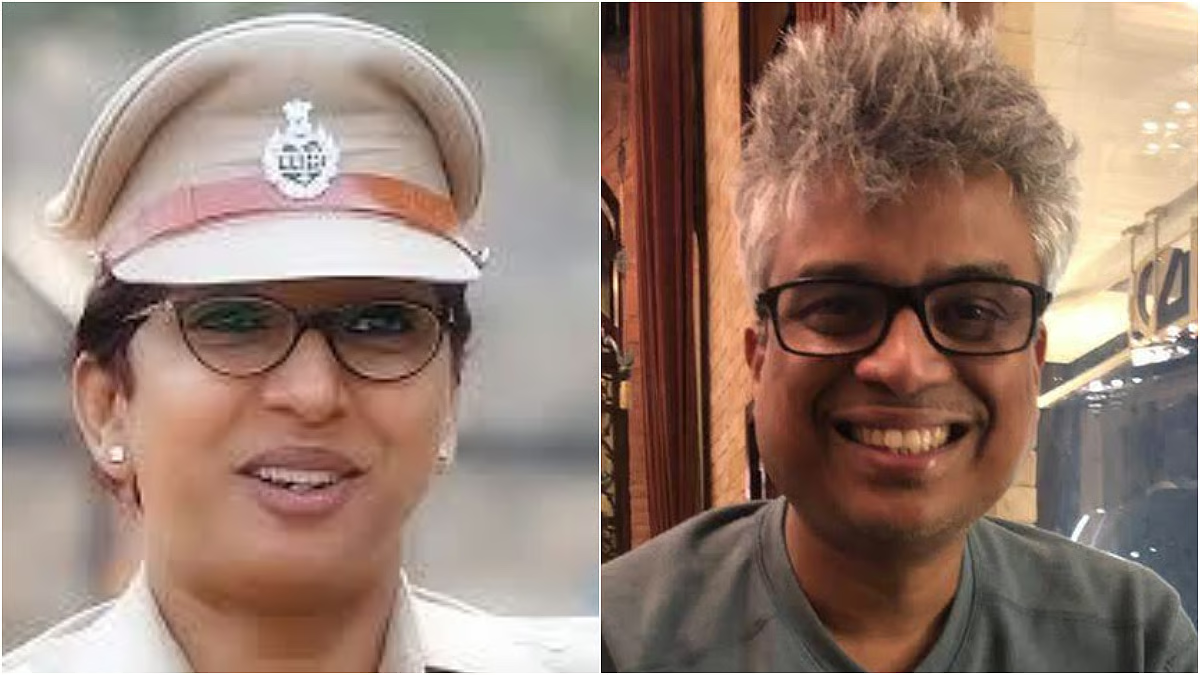

Following the news, IFS (Indian Forest Service) officer Varun Jain, a 2017 batch officer and the current Deputy Director of Udanti Sitanadi Tiger Reserve (USTR), began receiving phone calls from forest departments across the country.

Why the interest in Varun Jain? Because he is the brain behind the Chhattisgarh Elephant Tracking and Alert system – an app-based solution that has been in use for the past two years and is considered highly effective. Its success led states like Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha to adopt the same model.

So when reports surfaced of rising human-elephant conflict in Chhattisgarh, many officials from these states called Jain with a pressing question: “We implemented your model with great results-so why is it failing in your own state?”

To understand the reality behind the headlines, Indian Masterminds sat down with IFS Jain for an in-depth conversation about the challenges, the system’s true status, and what needs to change.

CHHATTISGARH ELEPHANT TRACKING AND ALERT

Mr Jain launched this app in Feb 2023, called ‘Chhattisgarh Elephant Tracking and Alert’ that works in collaboration with elephant trackers and human patrolling teams to identify the presence and movements of elephants.

Read Here More About It: How AI Helping Prevent Human-Elephant Conflicts in Chhattisgarh

THE APP THAT COULD SAVE LIVES – BUT ONLY IF IT’S USED

The Chhattisgarh Elephant Tracking and Alert app was developed to bridge the gap between real-time tracking and actionable alerts. It integrates data from elephant trackers and forest patrol teams to map the movements of elephant herds and issue timely warnings to vulnerable communities.

Before the app, Jain relied on manual methods. “We used to collect data from every forest division – where elephants were last seen, their location, movement patterns. I compiled all this in Excel, created maps, and sent them out,” he explains. The process was laborious and slow.

With the launch of the app in early 2023, the workflow improved drastically. Ground teams could instantly log sightings – whether it was an elephant’s presence, droppings, footprints, or other signs – into the app. This information would then generate real-time maps and alerts to nearby villages. Several divisions in Chhattisgarh began using the app, and soon, its effectiveness caught the attention of other states.

But the app’s success has one major caveat – it only works when used consistently.

A TECHNOLOGICAL FIX HINDERED BY HUMAN GAPS

“Many divisions start using the app, then stop for weeks or months before picking it up again,” Jain says. “This irregular usage defeats the entire purpose of real-time monitoring.”

This inconsistency has prevented the system from operating at full potential across the state. Meanwhile, in divisions where the app is used without interruption, such as Udanti, results have been striking: only one elephant-related incident has been reported in the last two years.

The app is now officially rolled out in all forest divisions in Chhattisgarh. Where it is consistently used, teams have built detailed corridor maps, tracking when and where elephants travel, rest, and feed. These insights not only help preempt conflict but also contribute to long-term conservation planning.

To enhance reach in remote areas, a siren system linked to the app via SMS has been introduced. If a sighting is logged near a village with poor network connectivity, the siren system is triggered through SMS to alert residents. Additionally, AI-powered cameras are being installed in strategic locations to automatically detect elephant presence, send alerts, and activate sirens – all in real time.

WHY THE IRREGULAR USE?

So what’s preventing full adoption? “We’ve conducted hands-on training in almost every division,” Mr Jain says. “But there seem to be two key issues – either the tracking isn’t being done at all, or staff need retraining on the entire model.”

He points out that the app was designed to be extremely user-friendly. “It takes less than a minute to enter a sighting. You just log the location and what was observed – whether it’s the elephant itself or signs of its presence.”

Meanwhile, traditional tools like radio collars have been phased out. “Elephants are incredibly intelligent. They learn to break or remove the collars,” says Jain. “That’s why we rely on foot patrol teams and the app-based system now.”

A MODEL FOR THE NATION – BUT CHHATTISGARH MUST LEAD

The irony is stark: while the app created in Chhattisgarh is producing results in other states, its inconsistent implementation at home is undermining its success.

The solution exists. It’s proven. But without continuous, committed usage by all forest divisions, this life-saving system will fall short of its potential.

As Jain warns, “Unless we use it uniformly and responsibly, both human and elephant lives will continue to be at risk.”