It’s 7 AM in the tribal villages of Odisha’s Sundargarh district. A group of women in vibrant sarees, armed with gloves, smiles, and a sense of purpose, hop onto tricycles and electric vehicles. Their daily route doesn’t lead to offices or construction sites but to doorsteps, alleys, and markets. They are known here as Swachhta Sathis, and the work they do is changing the very way people think about waste.

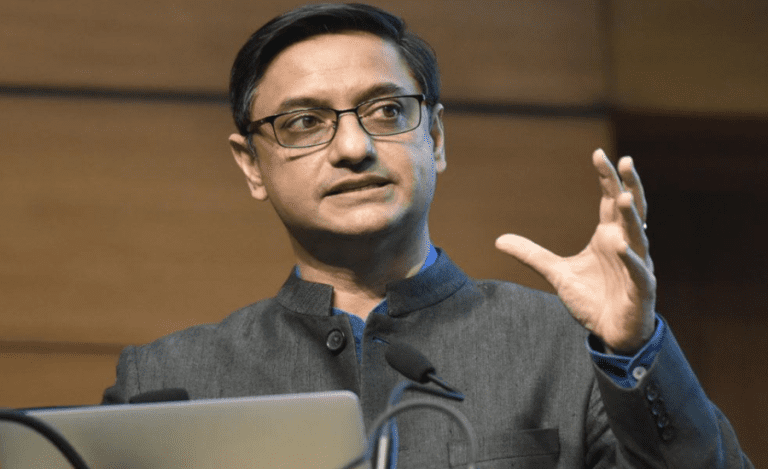

Behind this movement is IAS officer Manoj Satyawan Mahajan, District Collector of Sundargarh and a 2019 batch officer. What started as a waste management challenge in hilly, scattered villages turned into a full-blown grassroots model of sustainability, inclusion, and local pride.

WHAT HE SAW AND WHAT HE DID ABOUT IT

When Manoj Mahajan took charge, he noticed something that many had accepted as normal: heaps of plastic waste lining the roads, floating in ponds, or smouldering in backyards. As villagers burned waste or dumped it into streams, it was clear that there was no proper system. No solution. And no hope that things would change on their own.

The Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) was entering Phase 2. But rural areas like Sundargarh needed more than a slogan. They needed a structure.

“In my visits, I could see the lack of awareness and the helplessness. People didn’t know what else to do with the waste,” he shared in an interview with the media.

The solution came in the form of a new district-wide initiative in 2021, titled Aama Sundargarh Swachh Sundargarh. With UNICEF providing technical support, and a new model called Urban Rural Convergence helping bridge rural-urban gaps in waste disposal, Sundargarh was ready to do things differently.

TURNING WOMEN INTO WASTE WARRIORS

But what truly gave life to the project was the women.

The district began training rural women, not just to collect waste but to run the entire chain, from door-to-door segregation to operating shredders and balers. These weren’t token jobs. These were skilled roles that made them the core of the mission.

From one segregation unit in Kuarmunda, the model expanded to 1,682 villages, covering nearly 3.6 lakh households; almost 70% of the district’s rural population.

470 women now earn between ₹6,500 and ₹7,500 per month doing work that didn’t exist in their villages before.

PLASTIC: FROM TRASH TO RESOURCE

What happens after the waste is collected? That’s where the impact becomes even more layered.

- High-value plastic like PET bottles go to certified recyclers.

- Low-value plastic like multi-layered packaging is sent to cement kilns as fuel or used in road construction.

- Local Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) sort and prep everything.

So far, over 360 tonnes of plastic have been processed, and ₹17 lakh in revenue has been generated. This money goes back into maintaining the project – vehicles, training, salaries – making the entire system self-sustaining.

The project wasn’t without its challenges. With rough terrain and dispersed settlements, collection wasn’t easy. Mahajan’s team introduced customised battery-operated vehicles that made collection feasible even in the most remote locations.

RECOGNITION AND REAL IMPACT

In 2024, Sundargarh was awarded the Best Performing District in Plastic Waste Management under the Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin).

The investment? Around ₹14 crore.

The returns? Cleaner villages, empowered women, and a replicable model that balances environment, economy, and community.

During one of his visits, Manoj met a tribal woman who shared how her new job changed everything for her family. Once a homemaker, she now earns ₹6,800 a month, helps educate her children, and has become a respected member of her village.

LOOKING AHEAD

The district isn’t slowing down. Plans are underway to scale the program to 700 women by next year.

“This initiative is close to my heart,” Manoj shared with the media. “It’s not just about waste. It’s about respect, employment, health, and local ownership.”

Thanks to a well-thought-out system and women who believed in something new, Sundargarh today isn’t just cleaner; it’s more confident.

And all of it started with one question asked by an officer in the field:

“What if we could do this differently?”