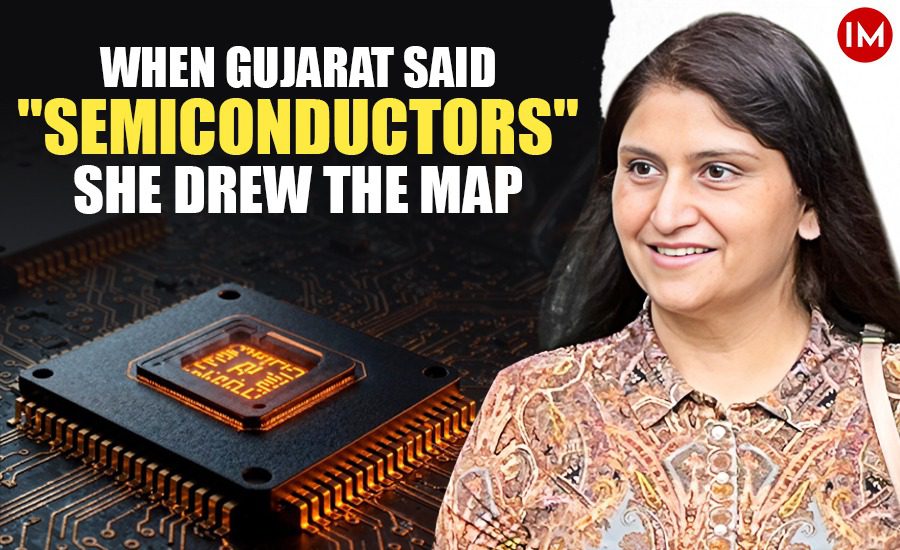

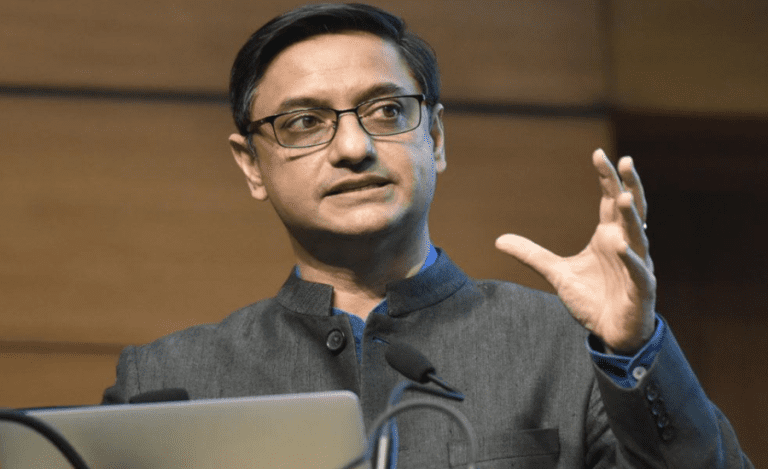

In the dimly lit corridors of policy and paperwork, Mona Khandhar doesn’t raise her voice, but you’ll know when she’s made a decision. Now serving as the Principal Secretary of the Department of Science and Technology, Gujarat, the 1996 batch IAS officer is leading the state’s push into one of the most complex sectors of our time – semiconductors.

It’s unfamiliar territory for many, not for Khandhar. “As a civil servant, I’ve learnt to adapt to new sectors and take the time to understand them thoroughly before planning and implementing strategies,” she once shared with the media. Her latest challenge? Making Gujarat the semiconductor hub of India.

And it’s not just lip service. She’s overseeing projects worth ₹1.24 lakh crore. Yes, crore, with factories by Micron Technologies, Tata Electronics, CG Power, and Kaynes Technology already in motion.

No Maps, Just Momentum

Gujarat’s semiconductor vision sounds futuristic. But at its core is old-school groundwork—land, electricity, approvals, and investor trust. Kaynes Technology was eyeing Hyderabad initially. Khandhar didn’t let it slide. Quiet follow-ups, logistical precision, and relentless backchannel coordination helped swing the decision in Gujarat’s favor.

Ask anyone in her circle, and they’ll tell you: she’s not easy to convince. She knows what she’s aiming for—and she rarely leaves room for doubt

From Harvard Classrooms to Gujarat’s Slums

This isn’t her first big shift. In 2014, fresh from a master’s in international economics at Harvard, she was made Housing Commissioner just before the general elections. Gujarat needed affordable housing and fast.

Between government red tape, skeptical slum dwellers, and impatient developers, most officers would tread carefully. Khandhar dove in. She helped shape slum rehabilitation policies and launched greenfield housing in Ahmedabad, Baroda, Surat, and Rajkot. Her efforts pushed private players like Adani and Godrej to reduce prices.

Building e-Villages Before It Was Cool

Long before “Digital India” became a buzzword, Khandhar had already moved on it. One of her earliest milestones was the eGram Vishwagram Project, which aimed to bring e-governance to Gujarat’s villages. Back then, people barely believed in digitizing cities, let alone remote blocks.

She didn’t just roll it out—she designed it.

When the Odds Were Tilted

Khandhar’s ascent hasn’t always been smooth. In a batch of 80, only 12 were women. She recalls how her independent thinking often drew puzzled looks or quiet resistance. There was skepticism about her ideas, her presence, even her intelligence.

But Gujarat, she says, was different. “While feudalistic attitudes exist, I found Gujarat to be relatively egalitarian,” she reflects.

The turning point? The early 2000s, when Narendra Modi took over as Chief Minister. For the first time, women in the service were given bigger, meatier assignments. Khandhar was among them.

Tokyo to Tablas: The Quiet Contrasts

Between 2019 and 2022, she served as Minister (Economics & Commerce) at the Indian Embassy in Tokyo. The precision of Japanese systems sharpened her strategic planning lens. But even with such high-level assignments, she never lost her softer side.

Classical music, dance, yoga, meditation—these aren’t weekend fads for her. They’ve been part of her life for decades. She even learned the tabla and sitar to accompany her own singing.

What’s Next? Probably Something Unwritten

Mona Khandhar doesn’t believe in calling something ‘final.’ Whether it’s semiconductor plants or slum housing, there’s always another layer to fix, another problem to pre-empt.

Her style is simple: understand deeply, act decisively, and speak when it counts. Gujarat’s semiconductor journey may be in its early stages, but with Khandhar anchoring it, there’s little room for drift.

Because when she’s in the room, things don’t just get discussed. They get done.