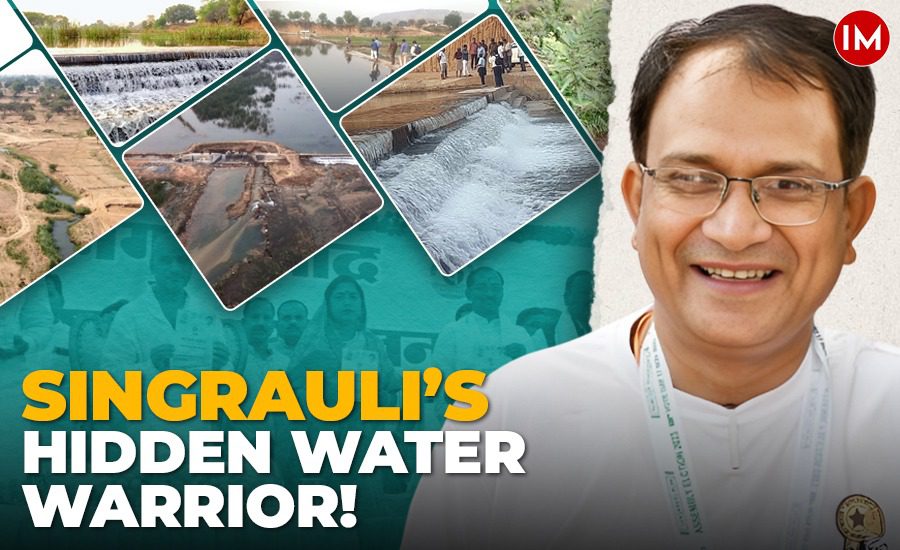

In a country where water scarcity threatens both rural livelihoods and ecological balance, stories of revival and resilience shine as beacons of hope. While Rajendra Singh, famously known as the “Water Man of India”, laid the foundation for water conservation models across the country, a new name is gaining recognition – 2001 batch IAS officer of MP cadre, Mr Gajendra Singh.

Posted as the Chief Executive Officer of Singrauli district in Madhya Pradesh, Mr Singh has undertaken an ambitious mission: to revive eight rivers across the district. His efforts have not only earned him accolades like the Jal Prahari Samman from the Government of India but have also ignited a movement of sustainable water management rooted in community participation and scientific planning.

Indian Masterminds recently interacted with IAS Gajendra Singh, Chief Executive officer Zila panchyat, to learn more about his remarkable work and the inspiring revival of rivers in Singrauli.

The Water Crisis in Singrauli: A Background

Situated in the north-eastern border of Madhya Pradesh, Singrauli is a district heavily impacted by industrial activity, particularly mining. With most of the land sloping northwards into the Ganga basin, the region is naturally rich in water resources. However, extensive mining operations and encroachment have led to the degradation of several rivers and a significant drop in groundwater levels.

Recognizing the urgent need for action, Gajendra Singh launched the Jal Ganga Samvardhan Abhiyan, a campaign focused on restoring river systems using a holistic, ridge-to-valley approach.

The Kanchan River Revival: A Model of Change

From a Seasonal Stream to a Flowing River

Once a seasonal stream that dried up by December, the Kanchan River in Singrauli had nearly disappeared after the construction of the Kanchan Dam in 1975. Encroachment of over 476 acres across its 29 km catchment – from villages like Phulwaritola, Gaderia, to Deori – further choked its flow. This led to a dramatic depletion of groundwater in the region.

Under Singh’s leadership, the district administration initiated a river revival project in 2022–23. The work began with silt removal and bank profiling in identified villages. Collaboration with landowners allowed the construction of boundaries and bunding structures, ensuring the river’s shape and flow could be maintained.

Gabion Dam: Engineering with Nature

A significant milestone in the revival was the construction of a Gabion cum Stop Dam in Gadhara village, costing ₹50 lakh from the District Mineral Foundation. Built without using steel, this structure was designed to suit the sandy riverbed and wide flow span (80–120 meters). The gabion design ensured water retention while minimizing ecological disturbance.

A gabion dam is a type of dam constructed using wire mesh baskets filled with rocks or stones.

After the completion, a 550-meter stretch of the Kanchan river now flows continuously, recharging wells and hand pumps and bringing visible improvement in groundwater levels.

Sustainable Water Structures: A Long-Term Vision

Beyond the physical revival of rivers, Singh’s model focuses on sustainability and community ownership.

Integrated Structures for Water Conservation

- Three additional gabion structures have been approved to sustain water flow.

- Groundwater recharge has improved significantly.

- Farmers are now active participants in conservation, recognizing the direct benefit to irrigation and agriculture.

Public Participation and Horticulture Plantations

In Gadhara, 12 acres of MNREGA plantations were developed by a women’s Sahayata Group. Singh’s vision extends to planting horticultural crops along embankments, both on government and private lands, to reinforce green cover and ensure income for locals.

Challenges on the Path to Revival

Reviving rivers is not without resistance. Mr Singh candidly notes that local anti-social elements have tried to disrupt the work – through misinformation and bureaucratic hurdles. However, with strong governance and public support, these obstacles are being addressed head-on.

Comprehensive Action Plan: Beyond Kanchan

Mr Singh emphasizes that the Kanchan River revival is just the beginning. His broader blueprint includes-

- Improvement of straight banks and vegetation clearance.

- Safe and permanent plantations on embankments.

- Private land involvement for long-term sustainability.

- Upstream ridge work and contour activities for erosion control.

- Survey of government lands in the catchment for potential conservation use.

- Tributary and drain structure mapping and development.

- Regular water quality testing via the Public Health Engineering (PHE) department.

- Digital tagging of water sources using the Jaldoot App.

- Timely surveys and project execution before monsoon seasons.

- These measures ensure not just revival but resilience of the water bodies.

A Replicable Model for India

The story of IAS Singh and the Kanchan River is not merely one of bureaucratic initiative but of visionary environmental stewardship. His holistic, participatory, and sustainable approach offers a replicable blueprint for river revival projects across India.

As climate change, population growth, and industrialization continue to strain India’s water systems, Singh’s efforts show that real change begins at the grassroots—with knowledge, integrity, and people’s involvement.

In the legacy of Rajendra Singh, the “Water Man of India”, it’s safe to say a new water warrior has emerged – this time from the coal belt of Singrauli.