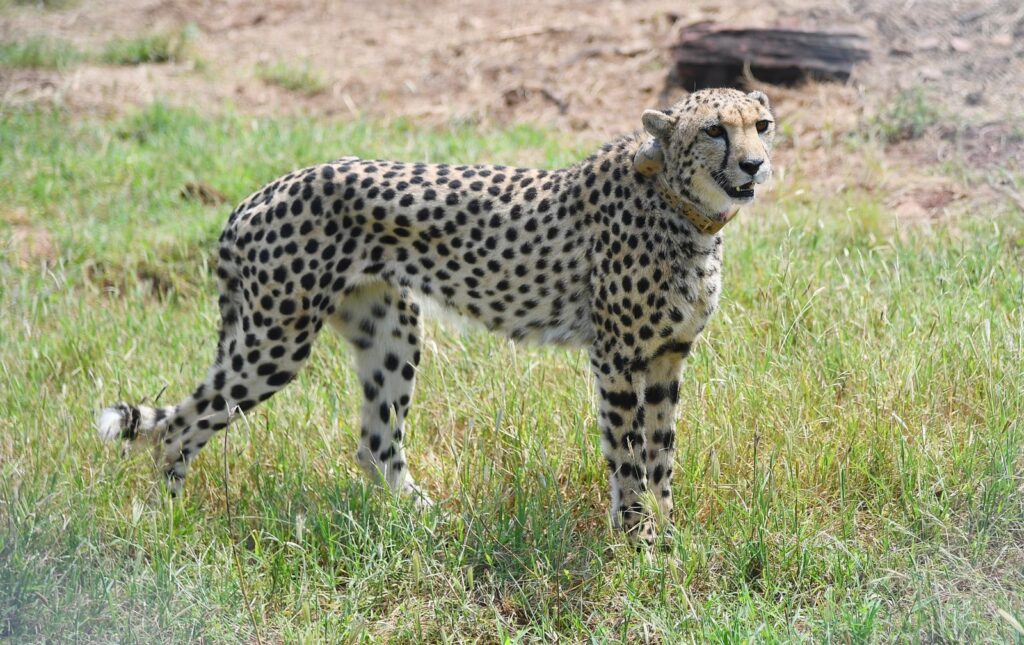

Today marks a historic moment, etched into the annals of wildlife conservation in India. On September 17, 2022, eight cheetahs – the world’s fastest land animals – were ceremoniously released into Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh as part of ‘Project Cheetah’. These magnificent creatures, brought back from Namibia in Africa, returned to a land they had been absent from since their extinction in 1952.

This event was not merely a milestone; it symbolized the ambitious rebirth of a species once lost to the Indian wild. Nearly eight decades after cheetahs were hunted to extinction in the country, the landscape of Kuno – often referred to as the heart of India – became their new sanctuary.

But after two years, has India achieved the success it envisioned? Have forest officials managed to create a conducive environment for the cheetahs? Have the cheetahs adapted to the Indian conditions? While two years may not be enough for a species to fully settle into a new habitat vastly different from their native one, these questions can offer a glimpse into the progress of Project Cheetah.

To gain more insight into the project, Indian Masterminds spoke with Mr. Uttam Kumar Sharma, the Chief Conservator of Forests and Director of the Lion Project at Kuno National Park. A 1999 batch Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer, Mr Sharma provided valuable perspectives on the current status and future of this ambitious initiative.

Project Cheetah: An Assessment of Progress

A closer look at Kuno National Park reveals a mixed picture for Project Cheetah. Of the original 25 cheetahs brought from Namibia, only one, named Pawan, initially ventured into the wild. Unfortunately, Pawan has since died in what forest officials have described as an accidental death. The remaining cheetahs are still confined to their enclosures, locally known as bomas, indicating that Project Cheetah faces several ongoing challenges.

Is this considered a success? According to Mr. Uttam Kumar Sharma, success is measured through short-term, medium-term, and long-term parameters. “In the short term, achieving a survival rate of over 50 percent in the first year is a positive outcome. Over the past two years, we have lost 8 out of 20 cheetahs, resulting in a survival rate of approximately 60 percent. Numerically, this is a positive result. Additionally, successful breeding has met another key parameter.”

Challenges of Adaptability

Currently, the most pressing issue is the cheetahs’ adaptability to their new environment. The cheetahs require more time to adjust to the vastly different conditions. While the ultimate goal is to release them into the wild, this is contingent on their successful acclimatization. Although progress has been slower than anticipated, there is optimism that the cheetahs will eventually adapt and be released.

Mr. Sharma explained, “The forest department is working to gradually acclimate the cheetahs to the wild while closely monitoring their adaptability. Two cheetahs have already spent nearly a year in the wild but encountered difficulties during the rainy season, which required their temporary confinement. They will continue to be gradually reintroduced into the wild, so the process is taking time.”

A Promising Start

At its inception, Project Cheetah was celebrated as a groundbreaking initiative aimed at reintroducing a species that once roamed India’s grasslands. The early signs were encouraging: cheetah numbers grew faster than the projected 5% annual increase, reaching a population of 25, including 13 adults and 12 cubs. Survival rates were also promising, with adult cheetahs faring better than anticipated at 65% and cubs thriving at an impressive 70.5%. Initial setbacks, including a few unfortunate deaths, were addressed, and the cheetahs appeared to be adapting well to their new environment.

Into the Wild, When?

However, a key issue remains – the cheetahs are still confined to their enclosures rather than being released into the wild. Despite their growing numbers, the majority of the cheetahs remain in their bomas. The original plan had anticipated that after a brief acclimatization period, the cheetahs would be transitioned into the wild. Yet, this crucial step has yet to be achieved for most of the cheetahs.

It is evident that the successes achieved under Project Cheetah so far are largely due to the controlled environment rather than genuine wild adaptation. The cheetahs are under constant monitoring, with veterinarians on standby and supplemental feeding provided as needed. While this level of care is beneficial, it does not replicate the challenges and independence of living in the wild.

Initially, the plan was for the cheetahs to be released into the wild after a two-month acclimatization period. By December 2023, a steering committee had approved this move.

However, the transition has been delayed, and officials are hesitant to commit to a new timeline. This delay raises concerns about the long-term effects of prolonged captivity on the cheetahs’ hunting skills and overall fitness.

Adapting to New Realities

The adaptation of cheetahs to their new habitat has been a complex journey. The Indian monsoon, which coincides with South Africa’s winter, presented unforeseen challenges. The high humidity exacerbated the cheetahs’ thick winter fur, leading to skin infections and, tragically, some deaths.

Although the cheetahs are gradually acclimating to the Indian climate, these initial hurdles underscore the complexities of such a transcontinental reintroduction effort.

The Predator Paradox

Kuno National Park, home to leopards – traditional apex predators – now shares its domain with the newly introduced cheetahs. Despite their distinct hunting styles and prey preferences, the coexistence of leopards and cheetahs raises concerns about competition. Leopards have been preying on the chital, a primary food source for cheetahs, leading to potential conflicts over dwindling resources.

Though no direct confrontations between cheetahs and leopards have been documented, the situation remains delicate.

The Wildlife Institute of India is conducting a survey to assess prey availability, and the findings will be crucial in determining whether the park can sustain both predator species without compromising their well-being.

The Path Forward

The road ahead for Project Cheetah is filled with many challenges. While the project has seen successes, such as increased cheetah numbers and survival rates, critical issues remain. Prolonged captivity, miscalculations regarding carrying capacity, and potential prey shortages all contribute to an uncertain future.

“Efforts are underway to address these problems and we are very hopeful,” Mr Sharma added. Plans to enhance Kuno’s carrying capacity through habitat restoration and improved fencing are being considered to mitigate human-wildlife conflict and provide better living conditions for the cheetahs.

As the project moves forward, the hope is that the cheetahs will adapt, thrive, and eventually reclaim their place in the wild. The next few years will be pivotal in determining whether this ambitious experiment can establish a sustainable cheetah population in India.

In the broader context of wildlife conservation, Project Cheetah represents both human determination and the intricacies of reintroducing a species into a new environment. As we reflect on the journey, we remain hopeful that this remarkable endeavor will pave the way for future successes in wildlife conservation.