High up in the grassland slopes of Himachal Pradesh, a quiet revival is underway. The vulnerable Cheer Pheasant, once on the brink of vanishing from these hills, is making a cautious return. Leading this rare conservation feat is IFS officer N Ravisankar, Deputy Conservator of Forests (DCF), Rohru, who has turned years of fieldwork and experimentation into a living, thriving reintroduction program.

“The Cheer Pheasant is not as flashy as the Himalayan Monal, but its ecological role is irreplaceable. We knew if we failed to act, it would disappear from our landscapes,” he shared in an exclusive conversation with Indian Masterminds.

FROM CAPTIVE BREEDING TO WILD RELEASE

The effort began decades ago at the Cheer Pheasant Conservation Breeding Centre in Chail, the world’s only functional breeding hub for this species. Over twelve years, keepers built a genetically diverse stock of birds. But breeding was just the beginning, the bigger challenge lay in returning these birds to the wild.

Early reintroductions in Seri village between 2018 and 2020 tested the limits of science and patience. Out of the first 18 birds released, only about 20% survived. Predators, harsh weather, and the birds’ struggle to adapt claimed the rest.

“Those first attempts were hard to watch,” recalls Ravisankar. “But every loss gave us clues: about predator-proofing, about timing, about how to train a bird raised in captivity to handle the wild.”

CHOOSING THE PERFECT SECOND SITE

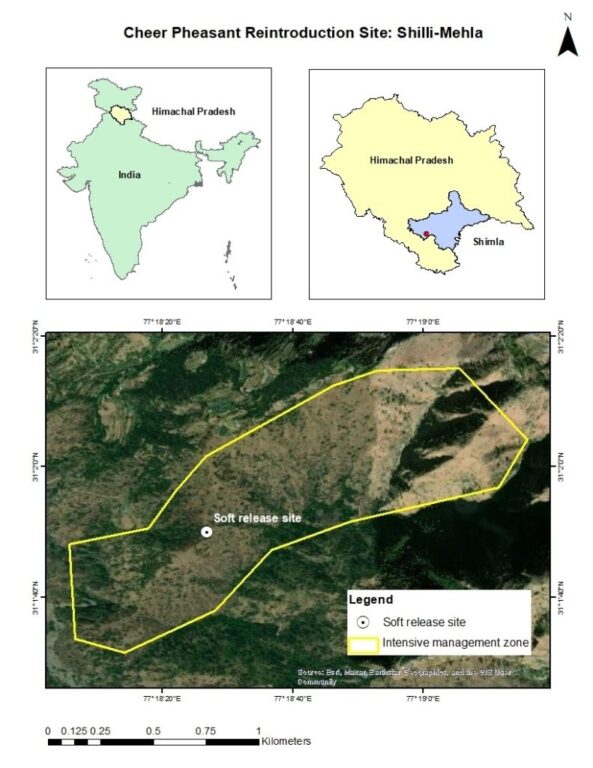

By 2021, the team needed a fresh site. A scientific survey across historical habitats, led with the help of biologist Akshay Bajaj and research assistant Rupali Thakur, pinpointed Shilli-Mehla village in Theog. Its open grasslands, sparse pine cover, and low predator density offered a natural refuge. Local villagers welcomed the project, proud to host what would become the world’s only active Cheer Pheasant reintroduction site.

BUILDING A SMARTER RELEASE

In 2023, Ravisankar’s team, now joined by research assistant Dip Dalai and forest guard Jitender Sharma, set up predator-proof soft-release pens. Tarpaulin padding, natural perches, and anti-hail nets reduced injuries. The birds were gradually weaned from grain mixtures to wild fruit and given “predator training,” including recordings of animal calls and even controlled encounters with dogs and remote-controlled decoys.

Before release, veterinarian Dr. Karan Sehgal screened each bird for disease. A few were fitted with VHF radio tags for post-release monitoring.

“This time, every step was deliberate,” says Ravisankar. “From diet to soft-pen design, we wanted the pheasants to feel the wild before they met it.”

A NEW DAWN FOR CHEER PHEASANTS

Eight birds were released at daybreak in October 2023, followed by another twelve in February 2024. Camera traps soon captured what the team had hoped for: 11 out of 12 birds survived, mingling with wild pheasants. By the next breeding season, chicks hatched from pairs of released and wild birds, proof that genetic mixing had begun.

“This was the moment we knew the landscape was alive again. Seeing camera-trap images of new chicks is something I will never forget,” Ravisankar shared with Indian Masterminds.

COMMUNITY AND CONSERVATION HAND IN HAND

Three local villagers now work as field assistants and night guards. Schoolchildren visit the site to learn radio-tracking basics. Villagers help keep dogs away from the release zone and monitor predators such as leopards, martens, and foxes.

Their involvement shows how conservation thrives when science meets community spirit. With 91% survival in the latest batch and confirmed breeding in the wild, the project is ready to expand to other sites of local extinction.

WHY IT MATTERS

Himachal Pradesh shelters seven pheasant species, two of them listed as “Vulnerable” by the IUCN: the Western Tragopan and the Cheer Pheasant. These ground-dwelling birds are indicators of a healthy forest ecosystem, and their loss would ripple through the region’s biodiversity.

By combining ex-situ breeding with in-situ reintroduction, Ravisankar’s team has created a model for endangered species recovery across India and beyond.

As he looks over the grasslands where the pheasants now forage freely, Ravisankar sums it up simply:

“Each call of a Cheer Pheasant at dawn tells us we’re moving in the right direction. It’s the sound of a species coming home.”