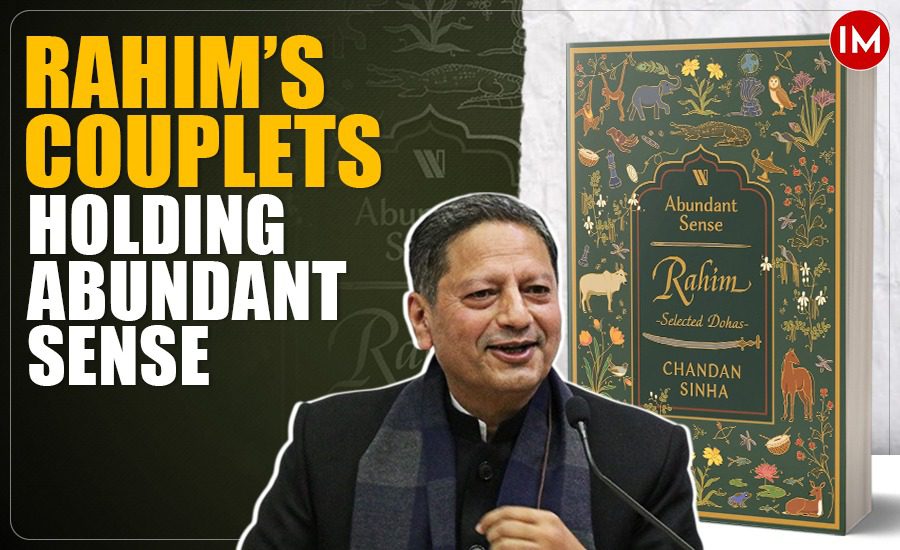

Abundant Sense | Chandan Sinha

Deeragh doha arath ke, aakhar thore aahin, Jyon Rahim Nat Kundali, simti kudi charhi jahin

(Couplets comprise a few letters, but hold abundant sense; As the crouching acrobat, Rahim springs atop the fence!)

This iconic two-line verse has two significant words, ‘abundant sense,’ which also give the volume its eponymous name. This is also reflective of each of the 144 dohas, which form part of this offering. A ‘doha’ literally translates into ‘two lines,’ but as Chandan Sinha explains in the introduction, there is something very special about the structure. The lines rhyme, and each line has twenty-four phonetic units called ‘Matras’; hence, not all couplets are dohas. The central message of a ‘doha’ – the rhyme induced surprise (John Hawley) seals the impact of the couplet with a figure of speech, most commonly a metaphor, and sometimes also an alliteration or assonance.

Before delving into the translation – in which Sinha has tried to retain every element of the original doha – words, phrases, context, order of segments, and the meaning – it is important to understand the persona of our muse. Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khana was one of the most powerful members of the Mughal elite in the court of Emperors Akbar and Jehangir, when the Mughal power was at its zenith. Brought up in the royal household, this polyglot held the highest position open to a ‘non-royal’ in the ruling dispensation. He had been Akbar’s trusted general, minister, governor, adviser, tutor to Prince Jahangir and for some time, the Vakil of the state. And yes, he was also one of the most prominent Braj Bhasha poets of his time, although he also wrote in Persian– the language of the court, as well as in Arabic and Turki. But his own ‘authorized’ biographer Abul Baqui Nihavandi (Ma’asir-i-Rahimi) does not hold his felicity as a poet as an important mark of distinction: he prefers to address him as ‘The General’. But in popular imagination, he is remembered as a man of words, for in this, his reputation is both formidable and everlasting. As Rushdie writes in The Victory City:

‘I have lived to see an empire rise and fall, How are they remembered now; These kings… those queens; They exist now only in Words, While they lived, they were Victors or Vanquished, or both; Now they are neither. Words are the only victors, What they did or thought, or felt, No longer exists; All that remains, is this city of Words’’

Just as Sinha had the challenge of selecting 144 of his oeuvre of 290 odd verses, I have the difficult task of selecting representative samples from the themes of Bhakti (devotion), Riti (Love) and Niti (Conduct). Thus in the Bhakti genre, I have chosen one each for Rama and Krishna.

Gahi sarnagati Rama ki, bhavsagar ki naav, Rahiman jagat udhar kar, aur na kachhu upaaya.

(Seek refuge at the feet of Rama – ship of the worldly sea. Rahim, beside this, from this world, nothing can set you free.)

Rahiman ko kou ka kare, jwaari chor labaar, Jo pati-raakhanhaar hai, maakhan-chaakhanhaar.

(What can they do to Rahiman, the gambler, thief, or knave? The guardian Lord, Lover of Butter, is there to save.)

In the Riti tradition, the two very popular verses are:

Rahiman teer ki chot te, chot pare bachi jaay, Nain baan ki chot te, chot pare mari jaaye.

(Rahim, if struck by arrows, you may yet survive, But you are finished, if you are pierced by striking eyes)

Rahiman, ek din ve rahe, beech na sohat haar, Vaayu ju aisi bah gayee, beechan pare pahaar.

(Rahim there was a time a necklace couldn’t come between us; And now there blows such a breeze that mountains come between us.)

Niti refers to forms of behaviour, norms of interaction, as well as the harsh realities of life. Thus describing the difficulty of being good, he presents the fundamental dilemma between the temporal and spiritual world in these powerful lines:

Ab Rahim mushkil padi, gaarhe dou kaam, Saanche se to jag nahin, jhoothe milen na Raam

(Now, Rahim, you are in trouble, both choices are hard, Truth does not yield this world, and lies don’t win you God)

Rahiman tab lagi thehriye, daan, maan, sammaan,’ Ghatat maan dekhiye, jabjin, turuti karie pyaan

(Says Rahim, remain a guest till warmth and welcome last; When you perceive respect decline, clear out of there fast.)

What was his personal spiritual disposition like? We can only conjecture, as Harish Trivedi has done that ‘he harboured in his heart two quite distinct possibilities – the one Perso Muslim, and the other Sanskrit – Hindu. And there was consummate compatibility between them, rather than conflict and contradiction, perhaps because they were held together by Rahim’s poetic imagination, and not by his personal faith’. But it becomes quite clear that metaphors from the Mahabharata, Ramayana and the Puranas were used quite liberally in popular discourse. For in the doha which derides both begging and deception, Rahim draws upon the foundational story of Kerala’s Onam festival: that of Lord Vishnu tricking the generous King Bali out of his kingdom.

Maange ghatat Rahim pad, kito karo barhi kaam, Teen paig Vasudha karo, tau baavne naam.

(Begging diminishes one, Rahim, however great the deal, Crossed the cosmos in three strides, yet known as a dwarf in need!)

The book may be purchased from this link…