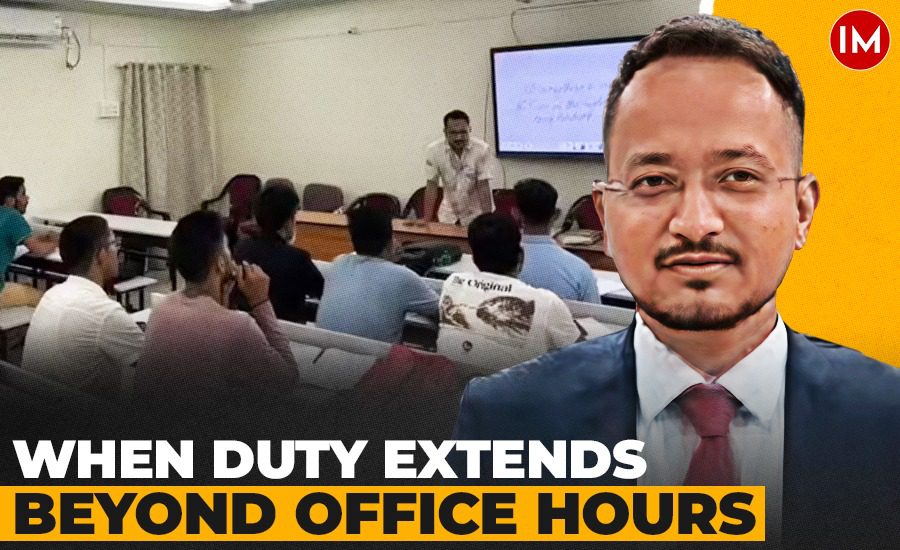

When most government offices close for the day, and files are set aside until morning, one officer in Assam begins his second shift — not behind a desk, but before a classroom. For Assistant Commissioner Asfaque Laskar, the end of an administrative day marks the start of a different kind of service: mentoring young aspirants who dream of cracking civil service exams.

Every evening in Bajali district’s Patshala, a town known for its educational heritage, Laskar gathers a group of students for free coaching classes. The lessons cover everything from General Studies and CSAT to strategies for tackling the UPSC and APSC exams. What began as a modest effort last year has quietly grown into a movement that is changing how rural students view competitive exams — not as an impossible dream but as a reachable goal.

THE SPARK BEHIND THE INITIATIVE

The idea took shape soon after Laskar himself cleared the Assam Civil Services (ACS) examination in 2024. While working as an officer, he noticed that despite Patshala’s academic reputation, there was a surprising gap in civil service guidance. Many students were unaware of the exam structure or lacked access to mentorship and study material. “Students here have potential but no direction,” he told the media, “I wanted to create that direction.”

That thought became the foundation for his initiative. With support from Nirmal Haloi College and a few fellow bureaucrats, Laskar began conducting structured classes in the evenings. He collaborated with a private organisation to ensure the programme could run sustainably. What started with a few curious students has now grown into a regular coaching setup that has been running successfully for several months.

FILING THE GAP RURAL ASPIRANTS FACE

Preparing for civil service exams is often seen as an expensive and urban-centric process. Coaching centres in Guwahati and other major cities charge high fees, making them inaccessible for students from rural or economically weaker backgrounds. Bajali, like many parts of interior Assam, has long faced this problem.

Laskar’s free coaching initiative provides an alternative — one rooted in accessibility and mentorship. “Most aspirants here can’t afford to travel or pay for private coaching,” he explains. “But with the right guidance, they can compete with anyone.”

The classes are held at Nirmal Haloi College, where students receive structured lessons, group discussions, and test sessions aligned with both state-level (APSC) and national-level (UPSC) examinations. Subjects range from history, polity, economy, and environment to current affairs, and Laskar often simplifies complex topics into practical, easy-to-understand lessons.

TEACHING WHILE PREPARING

What makes the initiative even more inspiring is that Laskar is simultaneously preparing for the UPSC exams himself. Between his administrative responsibilities and personal studies, he still finds time to teach. His dual role as both mentor and aspirant gives him a rare understanding of what students truly need — clarity, consistency, and motivation.

His teaching style reflects this empathy. Instead of delivering standard lectures, Laskar uses interactive methods — encouraging discussions, breaking down concepts, and guiding students on how to think critically rather than memorise. For many first-generation learners, this approach has opened a new way of understanding complex subjects.

A COLLECTIVE EFFORT

The initiative has not remained a one-person mission. Over time, several officers and educators from neighbouring districts have joined in, contributing their expertise to various subjects. Together, they have created a network of mentorship — a model that blends public service with community education.

Local authorities have taken note. District officials describe the project as “an example of how civil servants can strengthen society beyond official duties.” The administration has extended logistical support, and there are discussions about expanding the model to other educational institutions in the district.

EMPOWERING ASPIRATIONS LOCALLY

For students, the impact is immediate and tangible. Many of them, coming from modest households, had never imagined they could aim for administrative roles. Now, they find themselves discussing current affairs, writing practice essays, and debating public policy in the very classrooms that once seemed out of reach.

One student shared, “Earlier, we didn’t even know where to begin. Sir’s classes have shown us what to study, how to study, and most importantly, why to study.” Another remarked that Laskar’s example motivates them to “give back” someday, just as he does now.

The growing participation from both students and officers is turning the initiative into a small but meaningful community of learners. Each class ends not just with academic lessons but with conversations about integrity, public service, and the value of empathy in governance — ideas that are rarely taught in classrooms but deeply needed in administration.

BEYOND TITLES AND RANKS

Asfaque Laskar’s journey from a Guwahati-born aspirant to a serving Assistant Commissioner and mentor captures the evolving spirit of public service — one that sees governance not only as policy and paperwork but as people and progress.

His classroom in Bajali is not just producing future candidates; it is creating a mindset where young people believe they, too, can shape the system. By extending his service hours into mentorship, Laskar has shown that leadership does not depend on position alone but on the willingness to act when the day’s official work is done.

As his initiative continues to grow, and more officers and institutions join hands, the evenings in Bajali echo with a new kind of purpose — one driven by curiosity, learning, and the quiet belief that change often begins with a single person deciding to stay after hours.