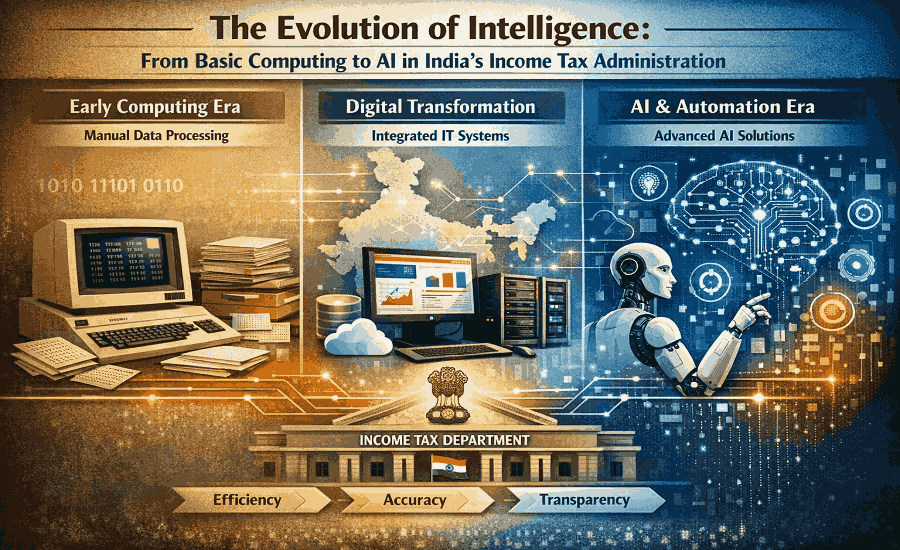

A deep dive into the workings of the Central Processing Center (CPC) and the Investigation Wing of the Income Tax Department reveals a nuanced ecosystem where basic computing automates the mundane, while advanced analytics and human prudence still govern the complex. The story of modernizing India’s tax infrastructure began long before the current AI boom. In the early 2000s, the department took its first tentative steps toward computerization, a vision largely credited to the late Rajiv Ranjan Singh, often regarded as the father of computerization in the Indian tax system.

At that time, the CPC operated out of the Bandra Kurla Complex and not in Bangalore. This foundational work was about ensuring that a machine could accurately replicate the rule-based decision-making required for processing tax returns.

A common misconception among the public is that the Central Processing Center (CPC) itself is an AI-driven entity. Its role is only to receive data from tax returns, process it against defined rules, and deliver an outcome – either accept the return or raise a demand. This is classic computing, not Artificial Intelligence.

However, the landscape shifts dramatically when one moves from routine processing to the investigation of tax evasion. This is where the department has begun to deploy tools that resemble AI, particularly under initiatives like Project Insight. Launched with the aim of creating a non-intrusive tax administration, Project Insight leverages big data analytics to create a 360-degree profile of taxpayers. Unlike the linear processing of the CPC, this system aggregates data from multiple disparate sources—banks, property registrars, credit card companies, and even social media—to identify patterns that appear anomalous.

The use of AI in this context is specific and targeted. For instance, when the department contemplates a search or survey operation, AI tools are used to scan through massive volumes of transaction data to find irregularities that would be invisible to the naked eye. The system is taught to look for specific red flags. It might search for a company that bypasses standard procurement processes, such as skipping the tender process to favor a specific vendor. It might flag a scenario where a business makes a large, unprecedented payment to a party with whom it has no history of regular interaction. By analyzing the frequency, volume, and timing of payments, the AI can map out relationships between entities, suggesting who might be colluding with whom.

These parameters are often set by human committees rather than the machine itself. Each year, a board of senior officers establishes the criteria for what constitutes a high-risk case, a process known as Computer Assisted Selection (CAS). The parameters are often dynamic and responsive to current economic trends. For example, in a specific year, the committee might decide to scrutinize all entities that purchased Electoral Bonds exceeding a certain threshold or those claiming refunds larger than five hundred crores.

Other logical checks might involve analyzing the stock-to-turnover ratio. If a company reports a massive turnover but maintains an unusually high stock level—say, exceeding fifty percent—it raises suspicion. A legitimate business with high turnover usually rotates its stock multiple times a year. A high stock level combined with high turnover might indicate inflated stock values to dress up a balance sheet for an IPO or to show artificial profits. These are the sophisticated parameters fed into the system to filter out cases for closer inspection.

This integration of technology has been further bolstered by the introduction of the Annual Information Statement (AIS) and the Taxpayer Information Summary (TIS). These tools represent the department’s effort to consolidate the massive influx of third-party data. Today, the department receives information on everything from foreign travel and high-value share transactions to mutual fund investments and cash deposits. The sheer volume of this data makes manual verification impossible, necessitating the use of advanced algorithms to match, merge, and clean the data before presenting it to the taxpayer.

Despite these advancements, there are significant limitations to what AI can achieve in the Indian context. Many tax deductions claimed by corporates are based on internal expenditures that do not leave a third-party trail. For example, a company might claim a deduction for installing a water treatment plant instead of a pollution control equipment. This claim is made via a form attached to the return, but there is no external database to verify whether the plant was actually built or if the costs are inflated. In such cases, the AI has no reference point to detect evasion. That can be done by human intelligence only.

This synergy between man and machine is further evident in the Faceless Assessment Scheme (FAS), a recent reform that attempts to eliminate human bias and corruption. While the allocation of cases in this scheme is handled by algorithms to ensure anonymity and randomness, the final assessment is still a human function. The officer behind the screen must interpret the data flagged by the system and the explanation offered by the taxpayer. The technology acts as a veil and a filter, but the adjudication remains a human endeavor.

Looking toward the future, the role of AI in the Income Tax Department is poised to grow, but likely as an assistant rather than a replacement. As data linkages improve—connecting GST networks, customs data, and international tax information exchanges—the predictive capabilities of the department’s systems will sharpen. We may see more pre-filled returns and real-time compliance nudges, where the system alerts a taxpayer to a potential discrepancy before they even file their return. This “nudge” approach is already being tested with campaigns sending SMS and email alerts about high-value transactions.

However, the notion that AI will eventually render human officers obsolete is unfounded. The complexity of financial engineering often outpaces the learning curve of an algorithm. Tax laws are subject to interpretation, and business realities are often messier than clean data sets. The future lies not in AI replacing the tax officer, but in the tax officer wielding AI as a powerful lens to see through the opacity of financial data, ensuring that the intent of the law—to tax the wealthy and support the nation’s development—is fulfilled effectively.