When the idea of reintroducing cheetahs to Indian soil was first floated, it was met with skepticism, resistance, and logistical challenges. The ambitious project, aimed at bringing back a species that had gone extinct in India over 70 years ago, seemed like an uphill task to many. But amidst the doubts and debates, a few officers stood firm in their belief and commitment to the cause.

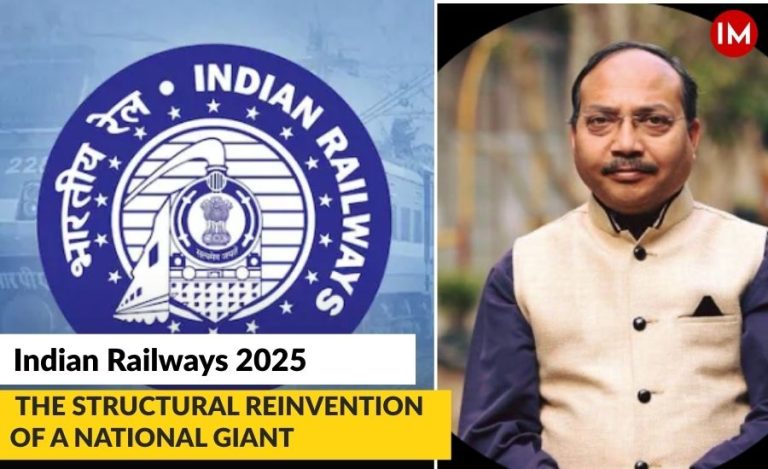

One such dedicated officer is Prakash Kumar Verma, a 2014-batch Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer, currently serving as the Deputy Director of Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve. His multi-faceted contributions to wildlife conservation – spanning cheetahs, tigers, elephants, and habitat management – have made a lasting impact across central India.

Indian Masterminds interacted with Mr Verma to gain deeper insights into his work, how he implemented key conservation initiatives, and the lasting impact they’ve had. “Conservation isn’t just about protecting animals – it’s about involving people at every step,” he shared.

The Cheetah Comeback: Turning Doubts into Reality

The reintroduction of cheetahs in India, particularly in Kuno National Park, was a landmark project. Mr. Verma played a vital role during this time, especially in habitat development and community engagement. Despite the uncertainty surrounding the feasibility of settling South African cheetahs in Indian conditions, he and the team forged ahead with scientific rigor and dedication.

“People said exotic cheetahs shouldn’t be brought to India, but the genetics were studied. They’re the same species. There’s no real difference,” Mr Verma explained.

In 2020, a turning point came when the Supreme Court of India approved the import and introduction of South African cheetahs. Mr Verma recalls, “The decision was sudden, but Kuno had already been studied back in 2012. It was identified as a suitable site with good grasslands and minimal human interference.”

With the foundation laid through prior surveys, the Forest Department acted quickly. 22 villages had already been relocated from the area, making Kuno a ready habitat. International collaboration followed – experts from South Africa visited, and detailed preparations began.

“From day one, everything was established. The entire project was built from scratch,” Mr Verma noted, adding that it was a massive inter-agency effort requiring coordination at every level.

Crisis to Reform: Elephants in Bandhavgarh

As Deputy Director of Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, Mr. Verma encountered a serious challenge – a tragic elephant mortality incident that shook the department. Instead of letting it stall progress, he turned the crisis into an opportunity for reform.

He strengthened elephant monitoring, launched awareness campaigns, and engaged deeply with local communities to prevent similar tragedies in the future.

“Awareness was the key. If people understand the behavior of elephants, they can avoid conflicts. Our team went village to village to talk, educate, and listen,” Mr Verma said.

This approach significantly reduced human-wildlife conflicts in the region, especially in elephant-prone areas, and showcased how community participation could serve as a powerful tool for conservation.

Scientific Conservation: Monitoring Tigers in Pench

During his posting at Pench Tiger Reserve, Mr Verma worked on scientific estimation exercises for tigers, co-predators, and prey species. These efforts enhanced the monitoring and management frameworks, which are critical for long-term conservation.

By implementing robust data collection systems and ensuring scientific integrity, he contributed to better decision-making models for reserve management and helped Pench become a model in evidence-based conservation.

Relocating with Dignity: A Model from Kanha

One of the most challenging yet impactful initiatives in Mr. Verma’s career was the relocation of villages from the Supkhar Range and Phen Wildlife Sanctuary in Kanha Tiger Reserve.

“Relocation always meets resistance. People are emotionally attached to their land. But we made it transparent, inclusive, and economically viable,” said Verma.

Instead of merely offering compensation, the team offered a sustainable and secure financial mechanism. They introduced CLTD (Corporate Liquid Term Deposit) accounts, where the relocation funds would not only be secure but also generate monthly interest income.

“A family depositing ₹15 lakh could earn ₹8,000 to ₹10,000 per month just as interest. This helped people feel safe and supported,” he shared.

By prioritizing transparency, land-based rehabilitation, and hand-holding support, the relocation turned into a success story. Many villagers who were initially hesitant began voluntarily requesting relocation after witnessing the benefits.

“It became an example. While other states were unable to use their relocation funds effectively, we not only used ours – we built trust with the people,” Mr Verma reflected.

A Legacy of Compassionate Conservation

Whether it’s helping settle cheetahs into new grasslands, resolving elephant conflicts, or relocating entire communities with dignity, Mr Verma’s approach has always been clear: science-backed decisions and people-centric execution.

His work across Kuno, Pench, Kanha, and Bandhavgarh shows how dedicated field officers can drive change not just in wildlife management, but in the hearts and minds of the people they serve.

“Conservation isn’t just about animals,” Verma said thoughtfully. “It’s about people too. Unless communities are involved, no project can sustain itself.”

The Man Behind the Mission

In an era where environmental challenges are growing more complex, officers like Prakash Kumar Verma stand as pillars of hope and action. His career is a powerful reminder that conservation is not a one-man job – but it does take one person to inspire a movement.