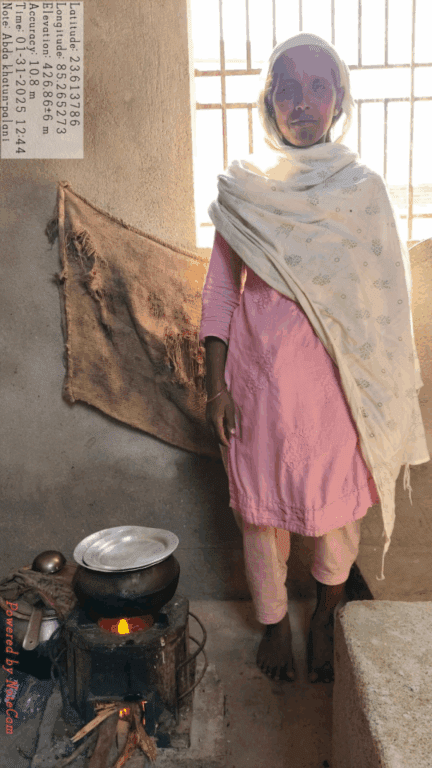

In the quiet villages of Jharkhand, an unassuming change is transforming lives, replacing the traditional smoky chullah with cleaner, thermal-efficient cookstoves. What began as a small initiative under a watershed project has now grown into a carbon credit revolution. Families who once inhaled thick kitchen smoke are now breathing easier and earning an extra ₹1,500 a year for it.

The secret? Carbon credits. Those invisible tokens of climate action that now hold real value for rural households. Through a unique collaboration between the Forest Department and NGO SIDHA (Social Initiative for Development and Humanitarian Action), these communities have stepped into the global carbon market. They are reaping both economic and environmental rewards.

Indian Masterminds exclusively spoke with IFS Nitish Kumar, DFO Ramgarh, and Mr. Hemant Kumar, the Director of SIDHA, to know more about the project.

WHEN FIRE MET INNOVATION

It all started when 4,600 improved cookstoves were distributed across Ramgarh, Koderma, and Jamtara districts. Each stove, with a thermal efficiency of 32%, replaced the traditional mud chullah that barely reached 2–5% efficiency.

The results were striking:

- 70–80% reduction in firewood use, easing pressure on nearby forests.

- Nearly complete combustion of wood, leading to almost no smoke.

- Cleaner kitchens and healthier women, who no longer spend hours surrounded by soot.

For women who once cooked with tears streaming down their faces due to smoke, this was more than technology; it was liberation.

“Traditional chullahs were not just inefficient; they were silent health hazards. Women were inhaling toxic fumes daily. With these stoves, we’ve seen a clear difference. The air inside homes is cleaner, and the forest outside is breathing better too,” says IFS officer Nitish Kumar.

THE CARBON CONNECTION

Behind this simple switch lies a complex process, one that connects remote villages to the international carbon market.

SIDHA worked closely with the Forest Division to register the initiative with VERRA, a global carbon registry. Each stove was tagged with a unique ID, and detailed data on wood savings and emission reduction was compiled into a Project Design Document.

After rounds of public review, verification, and audit, 6,300 carbon credits were officially issued, each representing a ton of carbon dioxide prevented from entering the atmosphere. These credits were then monetised, and part of the revenue was shared directly with the villagers.

“Every ton of carbon saved becomes a form of income. When you burn less wood, you emit less CO₂, and that difference has real market value. It’s like getting paid for protecting the planet,” Nitish Kumar shared with Indian Masterminds.

THE RISE OF GOBAR GAS AND CIRCULAR ECONOMY

While the improved stoves marked a milestone, SIDHA didn’t stop there. Realising the potential of rural circular economies, they expanded the idea to Gobar Gas plants: small biogas units turning cattle waste into clean energy for cooking.

So far, 150 Gobar Gas plants have been built, creating three smoke-free hamlets where every household now cooks using biogas. The leftover slurry goes back into fields as organic fertiliser, reducing dependency on chemical inputs and improving soil health.

“Reports from ISRO show that around 16% of Jharkhand’s land is facing desertification,” says Hemant Kumar, who leads SIDHA. “Through Gobar Gas and circular practices, we’re trying to reverse that trend. Our goal is to make this cluster of villages climate neutral by 2030.”

FROM FORESTS TO FUTURE

The initiative has also reduced human-wildlife conflicts by easing pressure on forests, as less woodcutting means fewer confrontations with wild animals. For communities living near forest fringes, this balance between livelihood and conservation is vital.

The next step is scaling up and replicating this carbon model across more districts. As Nitish Kumar points out, “Carbon projects are complex and require patience. Verification and registration can take years, but the outcome is worth it. Once established, these models sustain themselves, both economically and environmentally.”

THE BIGGER PICTURE

The Jharkhand model is more than a story of clean cooking; it’s about turning sustainability into shared prosperity. Integrating carbon markets into local development gives rural communities both a cleaner environment and a tangible economic stake in the fight against climate change.

For the women who no longer cough over smoky fires and for the forests slowly regaining their green cover, this change is deeply personal. It proves that meaningful climate action doesn’t always begin in conference rooms; sometimes, it starts in the humble warmth of a village kitchen.