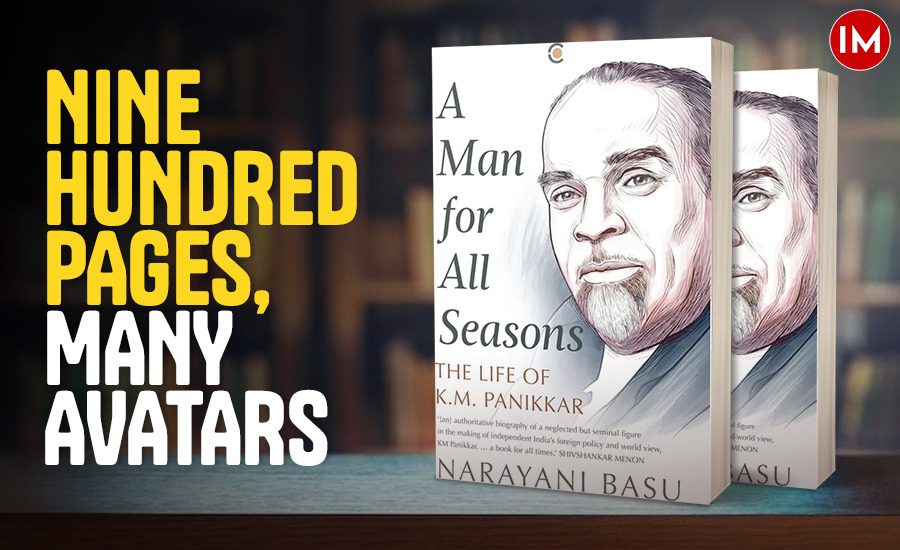

I seek the indulgence of my readers for an extended two-part review of about 2500 words for this well-researched hefty volume of close to nine hundred pages.

K M Panikkar could not asked for a better Ben Johson to document his life – for Narayani Basu has dug into such details which even KMP may have forgotten in the very rich, eventful and variegated life from 1894 to 1963: a period which saw him move from the backwaters to Travancore to a salient role in India’s foreign and domestic policy as our first ambassador to China and a key member of the SRC which marked the beginning of reshaping the internal boundaries of independent India.

Narayani Basu’s biography, “A Man for All Seasons: The Life of K.M. Panikkar” is indeed a comprehensive account of one of India’s most multifaceted, controversial, sometimes misunderstood man of many parts: polyglot scholar, diplomat, maritime historian Malayalam litterateur, journalist, Gandhi’s emissary, Dewan to princes and a man with a roving eye!

An alternate title to the book could well have been “A Man with all the Reasons”. Ms. Basu takes on a roller coaster ride through the diverse “avatars” of Panikkar’s life. We start with his childhood in Kavala detailing his family’s traditional background and the early intellectual environment that shaped his pluralistic worldview. His earliest and fondest memories are those of his grandmother Kunjipilla Gowri – a gentle, lovable woman who adored her grandchildren, and was open about her affections, instilled in him the love of Mulayam, and the stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharat. Early attempts at teaching him maths under the tutelage of his uncle Ayappa Pannikar failed miserably – he was often tied to a pillar for his youthful pranks including writing odes to a young village belle. He was then dispatched to Trivandrum, the capital city of the ultra-conservative Travancore state where rulers believed they were the descendants of gods and the guarantors of Hindu orthodoxy with caste-based restrictions at their peak. But change was in the offing – the matrilineal inheritance norms were being challenged through the Malabar marriage Act of 1896 and the Travancore Wills Act of 1899. Under the influence of Kerala Varma, primary schooling had been revolutionized, Nair supremacy was under attack, the Ezhavas were demanding equality, and the stranglehold of Sanskrit in education was being challenged by the Dravidian format. Even though ‘caning’ was a regular feature in Madhava’s growing up years, his love of poetry, philosophy and argument were strengthened by the intellectual environment at his elder brother’s home in Trivandrum which was a salon for the aspiring intellectual, legal and political elite of the town. But while he was excelling in language and literature, scions and maths overwhelmed him, and it was after great difficulty that he cleared the matriculation in his second attempt, which paved the way for his passage to Oxford in 1914 as a young, impressionable man of twenty.

While at Oxford, he made friends with Suhrawardy brothers, John Mathai, Dewan Chimanlal, BK Mallik, Hasanand Datija, VK Raman Menon and KPS Menon, among others. The Indian Majlis at Oxford Aso included students from Burma and Ceylon, and opened with the stirring lines of Vabre Mataram, and ended with a hymn of Allama Iqbal. The politics of Congress and the pan Islamist ferment among Muslims after the overthrow of the Ottoman Caliph were also high on the agenda. The three important issues that were uppermost in the midst of the young men there were Home Rule (in India), Universal Adult Franchise and the Impending War. Soon he started writing for Annie Besant’s Commonweal, Natesan’s Indian Review, and Bhasha Vilasam (in Malayalam), in which he argued the Dravidian meter was equally, if not more powerful than Sanskrit idiom to which the language pundits had succumbed. By 1916, he wrote ‘greater India’ for Ramananda Chatterjee’s The Modern Review which looked at the Hindu cultural influences extending from the Indian sub-continent to South east Asai. He won a handsome prize of Rs 100 for the best essay for the Indian Emigrant in which he expanded his concept of Greater India to include, not just the sacred geography of Jambudwip, but also the territories where the Indian diaspora had established its roots.

On his return to India in 1919, he was married to Gouri- the daughter of Ayappa Panikkar and took up his first teaching job at the Aligarh Muslim University where he wrote a seminal essay The Native states and Indian Nationalism. In addition to writing Indian nationalism: Its origin, History and Ideals. In this he was arguing that India had been a cultural entity since the time of the Vedas – and coming from a princely state himself argued that any plan for constitutional and political reform for India’s future had to take the princely states into consideration.

But he was not cut out for AMU, or vice versa, his friendship with Raja of Mahmudabad notwithstanding. So, he left a ‘secure’ job to join Swarajya, the paper established by Tantaguri Prakasam (Andhra Kesari) as an Assistant editor in 1923, which was also the year of the Viakom Satyagraha and the Congress session at Kakinada. It was at this session that the Congress passed the resolution that ‘temple entry was the birthright of all Hindus’. The following year, he went as Gandhi’s emissary to Amritsar to help with the Akali Shaykh Sabha and convince the Akali leadership that they had to focus on community issues, rather than the individual case of Nabha’s (forced) abdication. In the process he also convinced two of his main interlocutors- to set up a national newspaper in Delhi under the banner Hindustan, which later morphed into Hindustran Times. Apart from powerful editorials, the paper also ran stories about government profligacy and the scandals surrounding the Maharajas. Understandably, KMP had to quit in February 1925.

Unemployed at thirty-one, he decided to go back to England to become a barrister. His writings for newspapers, and his appointment as an examiner for the Indian history paper of the ICS kept him afloat, and even gave him some extra bucks for a trip to Europe where Panikkar met artists, art historians and freedom fighters from across the world, and had his torrid affairs with Germaine, Juliette and Veiller – Durray, but these do not find a mention in his rather bland memoir about his time in Paris. Full marks to Ms. Basu for showing KMP as he was – a brilliant man with a roving eye who also exercised an old-world discretion and charm about his extra marital affairs.

Meanwhile his book ‘An Introduction to the Study of the Relation of Indian states with the Government of India’ was published in London, and was noticed, among others by Colonel Kalish Nath Haksar, the Prime Minister of J&K who was in London as part of the Chamber of Princes delegation to discuss the future of paramountcy of the Emira and the relationship with Indian states before the committee headed by Sir Harcourt Butler. On his return passage to India I 1927 SS Ajmer where he had, among others Jawaharlal and Kamala Nehru and young Indira as co-passengers, he also wrote a 160 page monarch The Working of Dyarchy in India.In the interim, he accepted Haksar’s offer of joining the service of Maharaja Hari Singh the ruler of the twenty gun salute gun state of Riyasat-e-Jammu-wa-Kashmir-wa-Tibet- wa-Ladakh-ha (the official name of J&K) thereby beginning the next two decades of his life with the Indian princes.

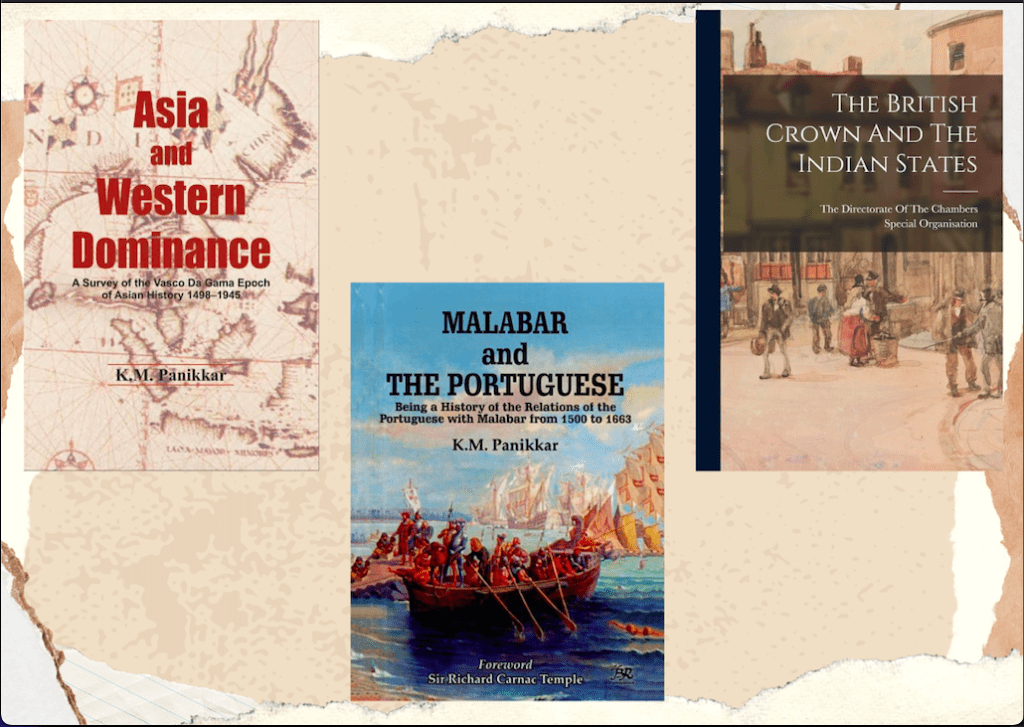

And thus that in 1929, the Panikkar family – which now included wife Gowri and three children- Parvathy, Madhusudan and Devaki arrived from the deep south to the geographically breathtaking, but politically volatile strategic frontier of Jammu & Kashmir. The vast majority of the Kashmiri Muslims resented the dominance of the Dogras, Kashmiri Brahmins and the Punjabi Hindus who were monopolizing the government jobs. Apart from Haksar, his colleagues included Sir Albion Banerji, P K Vattal and George Wakefield from the ICS. His specific task was to prepare a report on the Maharaja’s constitutional rights – for after 1857, the British desired to incorporate ‘the princely states into the imperial scheme of things, so as to consolidate colonial control’. They had to be ‘cultivated as allies, while being kept as subordinates’. But Panikkar argued that ‘princes retained all the powers that had not been specifically alienated in each of the individual treaties signed between the representatives of the Crown and the 570 odd states – many of which like J&K, Hyderabad, Mysore, Baroda and Hyderabad had territories, populations and incomes comparable to mid-sized European countries. All this was brought out in his monograph The British Crown and the Indian states. He was also busy with drafts of two more books – Malabar and the Portuguese in English, and a Malayalam fiction work based on the same theme.

However, even as the princes were obsessed with their status and gun salutes, India was changing very rapidly, and Congress was emerging as the major force in British India. A parallel organization, the All-India State Peoples Conference was making its presence felt in the princely states. Incidentally, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, a graduate from AMU became the President of this Congress affiliate in 1937/38. The attempts of the Round Table conferences to reconcile the conflicting interests and opinions in India came to a naught- especially as the views of the Congress, the princes, the Muslims League and the Depressed classes – represented by Dr Ambedkar – were at complete variance.

The second word War ended Pax Britannica, and its erstwhile colony across the Atlantic now rose to be the power to reckon with. The princely order did not realize that the ground had slipped from under their feet – and in their haste to finally quit India – which they found to be ungovernable – on account of the mass movement of the Congress, the intransigence of the ML, a revolt in the India Navy and the return of the INA soldiers, the British abandoned their ‘loyal allies’

The princely order ended – not with a bang, but with a whimper, but Nehru offered Pannikar the ambassadorship of China. When he joined in 1948, KMT ‘s ( nationalists) Chiang Kai-shek was still in power in Nanking (the then capital), but by then, almost all of northern China, with the exception of the Peking – Tientsin corridor and some areas in Manchuria had fallen under communist control.

Let us now come to the Tibet issue –on which Indian and Chinese perceptions were polar opposites. Whatever the internal differences between the KMT and CPC- both refused to accept the 1914 Simla Convention and the Mc Mahon Line, and had always questioned the ‘competence and legality’ of Tibetans to sign the border agreement. From 1945, the area adjacent to J&K was shown as ‘undefined border, and was represented with a coloured band that included the extensive (and yet uninhabited) Aksai Chin territory. When Panikkar received a note from the KMT regime that ‘the Chinese government wished to renegotiate the treaty of commerce and amity, including the borders between the countries’, Panikkar held his ground and said that the trade arrangements previously concluded by the British Indian government with Tibet could not be arbitrarily abrogated without consulting the Tibetans themselves’. By 1949, the Nationalists were on the run, and the Communists were encircling the cities. In a memo to Nehru, Panikkar had surmised ‘it can be assumed with practical certainty that the policy of a Communist China will be intensely nationalist. As the Soviet policy is the inheritor of the dreams of Peter the Great, the ambitions of Catherine and the conquest of the later Czars, the policy of Mao Tse Tung will combine the claims of all the previous dynasties from the Hans to the Manchus and will not voluntarily accept any diminution of territory, claims or interests which China inherited. He wrote of his experiences in the book In Two Chinas (1955) in which he compared the changes that took place from the KMT to the CPC.

Back home, India’s policy towards Tibet and China was caught in a quagmire: Patel voiced his differences with Nehru on the (likely) abandonment of Tibet and dependence on Communist China, and the foreign office under Bajpai and KMP also did not see eye to eye, and Nehru’s instructions were rather ambivalent. He was assuring Lhasa (Tibet) that he would take up their case with China, when he had no real intention of doing so. By 1950, TN Kaul, a professional diplomat was sent as his deputy to ‘keep an eye on the ambassador in Peking, who allegedly has a tendency to be excessively pro Chinese’.

Panikkar’s next diplomatic assignment was to Cairo where he presented his papers to Farouk 1, the king of Egypt and Sudan. This was the period when tensions over the Suez Canal were running high, but Gamal Abdul Nasser had not yet taken over as the helmsman of Egypt. Later Nasser became very close to Nehru, and was one of the main pillars of the nonaligned movement. While at Cairo, he wrote his important tract Asia and the Western Dominance – an ambitious book which threaded together his belief in an Asian sense of unity and common history. However, this marked a shift from his Greater India discourse. For Panikkar however, the best accolade came from Nehru, who told him to return to India to help him with the reorganization of states.

It must be mentioned that in the aftermath of Independence, Panikkar had been opposed to the linguistic reorganization of states. Writing under the pseudonym of Chanakya, he said ‘provinces organized on an ethnic and linguistic basis will inevitably develop regional patriotism and undermine the hard-won unity of India … it will give political expression to that feeling of local patriotism which will obscure the wider patriotism, which India wants to develop’.

However, after the SRC – which had Justice Fazl Ali as the Chair and parliamentarian HM Kunzru (as another member) toured the entire country, and received over 1.5 lakh memoranda, he realized the groundswell of support for linguistic states, and even though the committee was reticent about creation of smaller states in provinces which were bordering Pakistan (Punjab, Bombay and Assam) the major restructuring was accomplished. In fact, Panikkar also gave a dissenting note on the asymmetry between UP and all the other states of the country.

Later, as a member of the Rajya Sabha when India China relations had touched their lowest point, his Tibet – China policy was defended by Prime Minister Nehru himself, but the bitter criticism stung him, and he also realized that the Chinese had played their games, and that the border had impacted the geopolitics of the region, especially after the debacle of 1962. A year later, he breathed his last, and the next day, on the cold grey morning of 11th December, 1963, both houses of parliament rose to their feet in New Delhi, standing in silence for some time to pay their respects to a man who had been a giant of their time – and in whose shadow generations would walk for years to come.