Every winter and spring, Puducherry’s 48 kilometres of sandy coastline become the stage for an extraordinary natural cycle. Olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea), after travelling vast distances from the waters around Indonesia and Australia, arrive here to nest. These sea turtles are highly selective, choosing beaches with low human interference, minimal light pollution, and sand that offers the right thermal conditions for incubation.

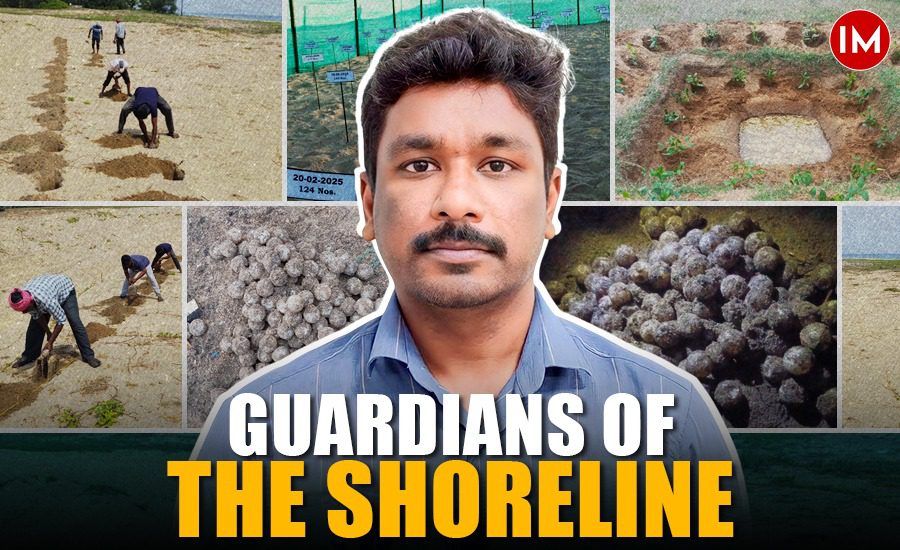

Overseeing their protection in Puducherry is Dr. P. Arulrajan, a 2009-batch Indian Forest Service officer who currently serves as Conservator of Forests and Chief Wildlife Warden. With a PhD in disaster management and a strong grounding in science, he has spearheaded a conservation programme that blends traditional fieldwork with cutting-edge technology and community partnerships. His leadership has transformed Puducherry into a model region for turtle conservation.

NESTING AND NATURAL INCUBATION

The turtles arrive on Puducherry’s shores between 2 a.m. and 7 a.m., guided by ocean currents. Each female lays around 100 to 150 eggs in a nest nearly two feet deep. The silicon-rich sand plays a critical role, retaining heat during the day and releasing it at night to maintain a temperature range of 25°C to 37°C. This temperature gradient determines the hatchlings’ sex—warmer zones producing females and cooler layers producing males.

“The olive ridleys have perfected their nesting behaviour over millennia. They don’t just dig holes randomly; they layer eggs in a way that balances the sex ratio naturally,” Dr. Arulrajan shared in a conversation with Indian Masterminds.

The incubation lasts 50 to 60 days before hatchlings emerge and instinctively crawl towards the sea. Their survival, however, depends heavily on whether nests remain undisturbed by predators, human activities, or environmental fluctuations.

IN SITU AND EX SITU CONSERVATION

Dr. Arulrajan’s team uses two approaches: in situ and ex situ conservation.

In situ conservation protects eggs at the site where they are laid. On undisturbed stretches such as Auroville’s beaches, success rates are exceptionally high—around 98–99% hatchability. “Nature knows best. When the nesting site is safe, our role is simply to ensure it remains undisturbed,” says Dr. Arulrajan.

Ex situ conservation becomes necessary in vulnerable areas close to fishing settlements or tourist spots, where predators such as dogs, foxes, jackals, and birds, along with human activity, threaten eggs. Forest officers patrol the beaches between 3 a.m. and 7 a.m., relocating freshly laid eggs to secure hatcheries. These hatcheries, designed with protective netting and sheds, recreate natural conditions.

The results are striking. Ex situ hatchability rates improved from 69% last year to 83% this year, thanks to better training, monitoring, and technology. In contrast, in situ sites continued to deliver near-perfect success.

“Relocation has to be done within minutes of the eggs being laid; otherwise, even minor delays can disturb the thermal balance crucial for development,” explains Dr. Arulrajan.

TECHNOLOGY FOR SMARTER CONSERVATION

Covering 48 kilometres of coastline with limited manpower is a daunting challenge. To address this, Dr. Arulrajan has introduced advanced technology into conservation planning.

By digitising nesting data collected since 2009, his team built predictive models using artificial neural networks and support vector machines (SVM). These models, coded in Python, can now predict high-probability nesting zones with an accuracy of 92–93%.

“With data-driven predictions, we no longer need to stretch patrols thin across the entire coastline. We focus resources where turtles are most likely to arrive,” says Dr. Arulrajan.

This system reduces the need for widespread staffing, allowing officers to concentrate on just 1–2% of the coast for vehicle-based monitoring. It also helps prioritise in situ conservation in safer areas and ex situ measures where risks are higher.

SCIENTIFIC COLLABORATIONS

Partnerships with Pondicherry University have further strengthened conservation efforts. Researchers and students not only verify hatchability rates but also study factors such as sand types, beach slopes, and diurnal temperature variations.

“Universities bring scientific depth and young energy to the field. Their studies are helping us refine prediction models and set benchmarks for other coastal regions,” says Dr. Arulrajan.

These collaborations are backed by government funding, ensuring that the insights generated in Puducherry can influence conservation strategies along India’s wider coastline.

COMMUNITY AS CUSTODIANS

While technology and science play a crucial role, local community participation underpins the programme’s success. Coastal residents, schools, and even hospitality businesses comply with restrictions on vehicle movement and adventure sports from December to June, the nesting season.

The involvement of senior administrators, including Chief Secretary Sharat Chauhan, in patrols and awareness events has created a culture of shared responsibility.

“Poaching has been eliminated completely. Today, even hotels and restaurants along the shore understand why we ask them to minimise disturbance. Conservation has become a collective responsibility,” Dr Arulrajan shared with Indian Masterminds.

Training local youth and staff, many of whom studied only up to the 10th or 11th grade, has been another significant achievement. With precise instruction, they now handle nest monitoring and data collection with accuracy. Weekly site visits by Dr. Arulrajan himself ensure that standards are maintained.

“When community members become guardians of nests, it is no longer just a government program. It becomes part of local identity,” he notes.

OUTCOMES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Last year, tens of thousands of eggs were safeguarded through a combination of in situ and ex situ efforts. Hatch rates are steadily improving, and the use of predictive technology has enhanced efficiency. Plans are also underway to publish findings in scientific journals, ensuring wider dissemination of Puducherry’s model.

“Every hatchling that reaches the sea carries forward a story of teamwork—of science, officers, and citizens coming together,” reflects Dr. Arulrajan.

Looking ahead, the focus will remain on refining data-driven prediction, expanding awareness, and maintaining the delicate balance between natural nesting and human intervention.

Puducherry’s olive ridley conservation effort demonstrates how science, technology, and community engagement can complement each other. By combining predictive modelling, careful fieldwork, and grassroots participation, the programme not only protects a vulnerable species but also builds a template for coastal conservation across India.

As Dr. Arulrajan puts it, “The turtles have chosen Puducherry for centuries. It is our duty to ensure they continue to return—and that when they do, the beaches are safe for their survival.”