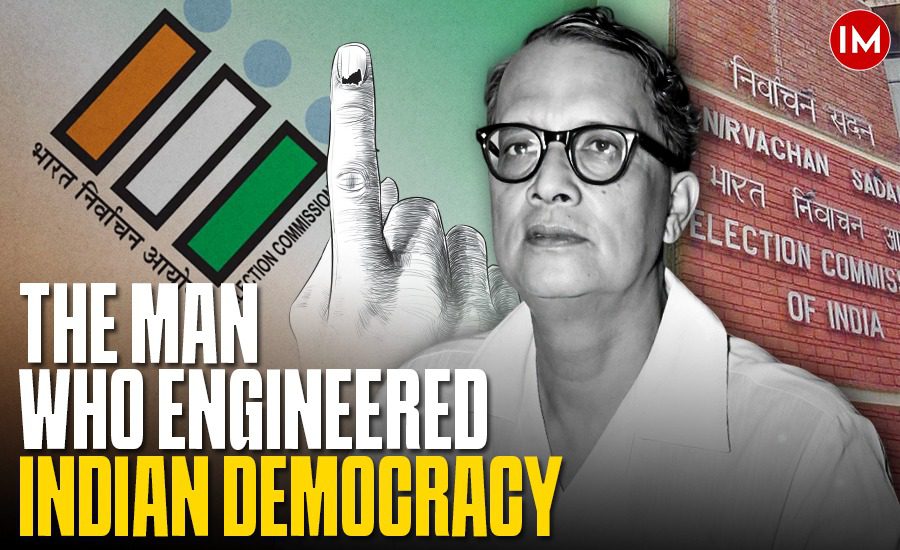

Sukumar Sen (2 January 1898 – 13 May 1963) occupies a unique place in India’s modern statecraft: a quiet, methodical civil servant whose technical skill and administrative rigour turned an audacious idea—universal adult suffrage in a newly independent, largely illiterate country—into a functioning reality. Appointed India’s first Chief Election Commissioner in March 1950, Sen mapped out and executed the logistical miracle that delivered the country’s first general elections in 1951–52 and again in 1957, laying the institutional foundations that continue to sustain Indian democracy.

Born in Bengal, Sen was an outstanding student and trained mathematician who joined the Indian Civil Service in 1921. His grounding in numbers and systems—he won a gold medal in mathematics at the University of London—proved well suited to the daunting task before him: designing voter rolls, delimiting constituencies, choosing vote-recording methods, and organising polling across diverse terrains and communities. Before his election appointment he had risen to be Chief Secretary of West Bengal, experience that acquainted him with grassroots administration and electoral preparations.

What made Sen exceptional was both his technical imagination and his institutional caution. He resisted political impatience—famously telling contemporaries, including Prime Minister Nehru, that the country was not yet ready until the necessary census, electoral rolls and legal framework were in place. Once the preparatory work was done, he executed the polls with surgical precision: the 1951–52 elections were held in numerous phases over several months, used coloured ballot boxes and paper ballots tailored to low-literacy conditions, and enfranchised nearly 100 million voters for the first time. The scale and success of that exercise won domestic applause and international attention, and established operational templates—roll compilation, polling procedure, secrecy of the ballot—that the Election Commission still follows.

Sen’s stewardship was not merely managerial; it was nation-building. He transformed the abstract constitutional promise of universal suffrage into practical, verifiable participation. That achievement earned him the Padma Bhushan and later institutional remembrance—the Election Commission of India instituted the annual Sukumar Sen Memorial Lecture in recognition of his role. His approach combined respect for legal safeguards, attention to procedural detail, and an insistence on administrative neutrality—qualities that define the ideal of a professional, impartial civil service.

Why call Sukumar Sen a “legend” of bureaucracy? Because legends in administration are not made by charisma but by creating durable systems that outlast individuals. Sen’s legacy is structural: he turned a fragile, novel experiment in representative government into a repeatable, scalable process that enabled the largest democratic exercise in history. For a country whose democratic institutions have since weathered enormous strain, the fact that India’s electoral machinery was designed to work for the many—not the few—is a testament to Sen’s foresight. His life reminds us that competent institutions, painstakingly built and scrupulously defended, are the quiet engines of democracy.