Far away from city streets and school bells, deep inside the thick forests of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a unique school now stands — not just as a structure, but as a symbol of hope, respect, and careful inclusion.

The school, built in a sensitive zone inhabited by the Jarawa tribe — one of the world’s oldest and most isolated hunter-gatherer communities — has been formally handed over to the community. For a tribe that has long shunned outside contact, this milestone marks a quiet but powerful step towards education without compromising identity.

A LONG WALK TO THE CLASSROOM

Earlier, attempts were made to build schools for the Jarawa tribe, but they didn’t stand the test of time. The structures, made with temporary materials, couldn’t withstand the harsh forest conditions—and with the tribe being nomadic, those schools soon became abandoned. “This time, we wanted to create something lasting and truly useful,” said Dr. Abdul Qayum, the Indian Forest Service officer who led the initiative to Indian Masterminds. Dr. Qayum is an IFS officer of 2013 batch and AGMUT cadre.

The location of the school was no ordinary construction site. Dense jungle, rocky hills, and the absence of roads made access nearly impossible. The materials had to be transported over water and land in ways that tested the patience and physical limits of the team.

“All the construction material was first loaded onto boats,” explains Dr. Abdul Qayum, the Indian Forest Service officer who led the initiative. “From there, it had to be carried on foot over hilly and forested terrain. Men walked for hours, balancing loads on their heads. We made over 90 boat trips to move everything.”

Cement wasn’t an option due to forest regulations, so durable wood and special sheets were used instead. The structure resembles traditional tribal huts, offering a familiar and welcoming feel. The goal was to create a learning space that didn’t look foreign or threatening to the community.

DESIGNED FOR THE JARWAS

The Jarawas, estimated to number between 250–400, move across regions in Middle and South Andaman. Though they remain largely secluded, they do stay in certain locations for several months at a stretch — making it possible to introduce steady services like schooling and healthcare.

“This isn’t about forcing change. It’s about offering education in a way that respects their world,” said Dr. Qayum. “We’re bringing learning to them — in their language, in their space.”

To ensure that, the administration plans to recruit teachers who understand the Jarawa dialect and cultural norms. Children will be taught in their mother tongue, and the school environment has been designed to be non-intrusive and welcoming.

The inauguration was a quiet and powerful moment. Two elderly members of the Jarawa tribe, selected by the tribal welfare department, performed the opening. No officials, no ribbon — just community presence and silent acceptance.

A HISTORY OF THOUGHTFUL STEPS

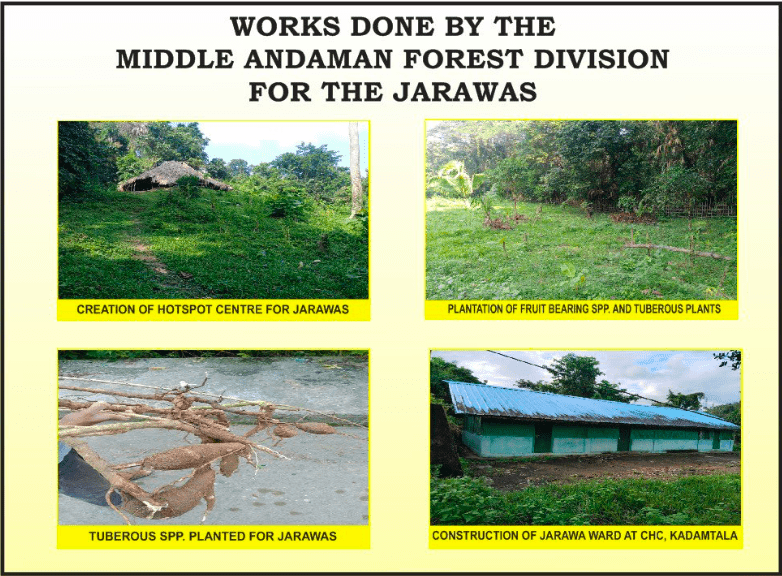

This school is the latest in a series of initiatives designed to uplift the Jarawa community without disrupting their lifestyle. Over the years, authorities have set up dedicated tribal-friendly healthcare wards, distributed voter ID cards to adult members, and built a hut at the Nature Interpretation Centre to preserve and display their cultural heritage.

To support their nutrition, the forest department even launched a captive breeding program for Andaman wild pigs — a vital food source for the Jarawas — and reintroduced them into the forest three years ago. Fruit-bearing and tuber plants are also regularly cultivated in their area.

Middle Andaman’s forest and tribal welfare teams have worked together to ensure that development efforts are inclusive, not intrusive.

MORE THAN A BUILDING

What makes this school different is not just its location, but its spirit. It’s a rare case of development that listens before acting — that respects the rhythms of a tribe rather than forcing it to change.

“This is just the beginning,” says Dr. Qayum. “We’ve built a school, yes — but more importantly, we’ve built trust. Now, we let the children take it forward.”

As sunlight filters through the forest canopy and settles on the wooden roof of the new school, a new chapter quietly begins — one written in the language of the forest, by its youngest storytellers.