A sensitive issue within the Forest Department should have been handled with care, but instead, it was portrayed as a failure on the part of the department. Despite the fact that the Forest Department was fulfilling its responsibilities, it was the department itself that released the controversial report. Over the past month, there has been a significant uproar over the news that 25 tigers were missing from Rajasthan’s Ranthambore National Park. The park is home to a total of 75 tigers, but a monitoring committee report released in October stated that there was no concrete evidence of the existence of 25 of them.

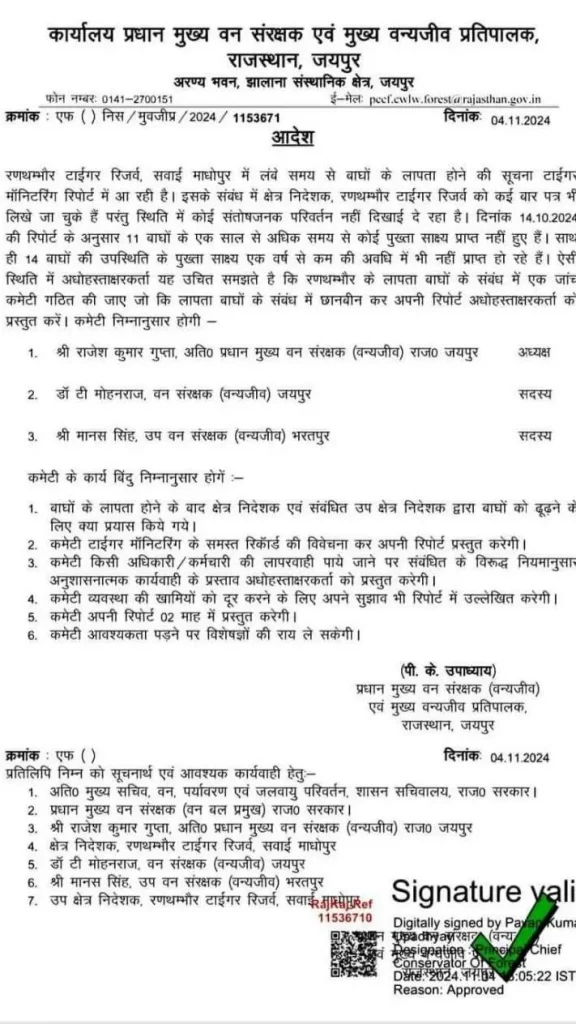

In response, the department swiftly formed a new committee to investigate the matter. The committee, led by Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (APCCF) and IFS officer Rajesh Kumar Gupta, has since confirmed the presence of 11 of the 25 missing tigers, with further updates expected soon. However, the way the issue was presented by the mainstream media focused more on casting blame than on providing accurate information about a highly sensitive situation.

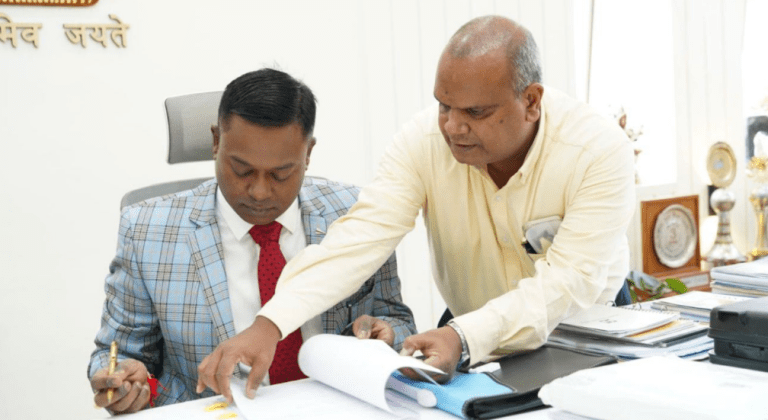

To gain a deeper understanding of the situation, Indian Masterminds spoke with Mr. Pavan Kumar Upadhyay, a 1992 batch Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer and the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (PCCF) & Chief Wildlife Warden (CWLW) of Rajasthan, to uncover the true nature of the issue.

THE REPORT

On October 14 of this year, the Rajasthan Forest Department received the Tiger Monitoring report, which revealed that 25 tigers were missing in the state. Of these, 11 tigers had not been confirmed through camera traps or other monitoring methods for the past year. Additionally, 14 tigers were not tracked for the last six months, with little information available about their whereabouts. In response to this report, the department immediately formed a committee to investigate further.

When the updated Tiger Monitoring report was released on November 5, it confirmed that concrete evidence of the presence of 10 out of the 14 tigers had been found. This evidence included tiger marks captured by camera traps, complete with date, time, and location. However, the department does not typically share such detailed information publicly, nor do they disclose the individual tiger numbers, as this could put the animals at risk.

In fact, the department had already been preparing a weekly monitoring report since October. According to the department, evidence for the remaining four tigers out of the 14 is expected to be found soon. Mr Upadhyay explained, “During the monsoon, tigers often leave their territories and move to other areas. They may cross corridors and migrate to other tiger reserves or even other states.”

NOT THE FIRST TIME

This is not the first time the department has faced a situation where tigers were unaccounted for. Similar incidents have occurred several times in the past in Rajasthan. According to PCCF Mr Upadhyay, this has happened five times before, each time triggering an inquiry. In these cases, either a committee was formed or a senior officer was appointed to investigate the matter.

When asked about allegations of negligence within the department, Mr. Upadhyay responded, “There is always room for improvement. We must continue to refine our work. We’ve released this report, and we are actively addressing the issue. Yet, we are being blamed for negligence. Our intentions are positive; we are not here to harm anyone. Our goal is to improve the system. This directive was issued with the aim of enhancing our operations, not to demoralize anyone.”

THE COMMITTEE

The committee has been given a two-month timeframe to complete its work. However, the department is referring to it as a “corrective committee” rather than an investigative one. The goal, they say, is for the committee to offer recommendations on how the monitoring system can be improved, making it a fact-finding mission.

The committee will assess whether concrete evidence of these missing tigers can be found within the next two months. Additionally, the department is conducting age profiling on these tigers to better understand their conditions. As PCCF Upadhyay said, “For instance, if we have a tiger that is 18 years old, it raises the question—could such an elderly tiger survive long in the wild? While it may be able to live in captivity, it may not be able to thrive in the wild.” Therefore, the true status of these 11 tigers will only become clear once the committee’s report is released.

He further emphasized that, “Not only that, but we also want a clear protocol to be established for handling cases where concrete evidence of a tiger’s whereabouts is missing for an extended period, as outlined in the NTCA’s Standard Operating Procedures (SOP).”