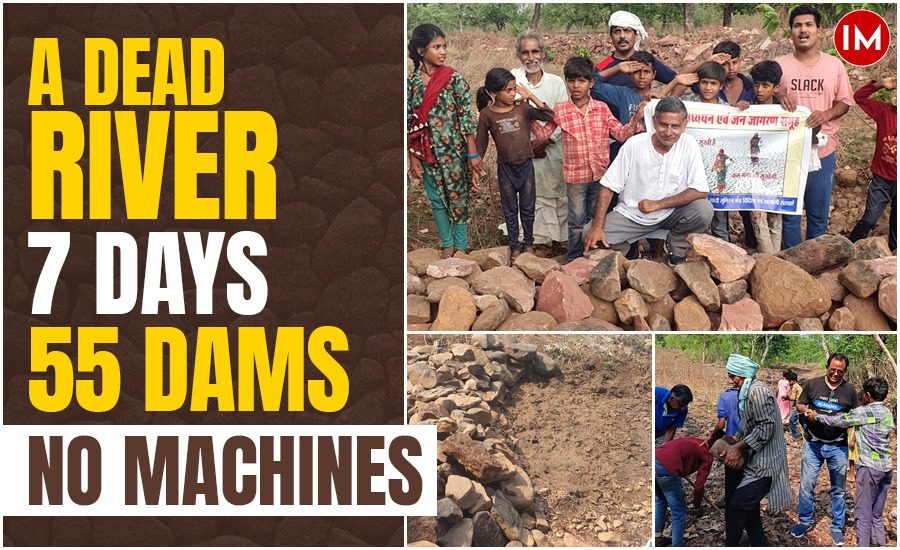

On a blazing May afternoon, while most people hid behind air conditioners, a 64-year-old man stood knee-deep in a dusty trench in Jhiri village, Raisen district, packing stones into a handmade check dam with his bare hands.

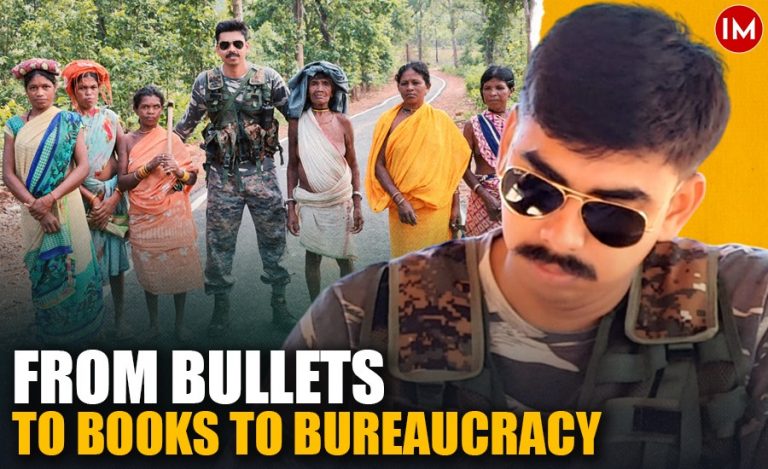

He wasn’t a farmer. He wasn’t a contractor. He was Dr. R.K. Paliwal, a 1986-batch IRS officer who recently retired as the Principal Chief Commissioner of Income Tax for Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

But here, in this forgotten corner of central India, he wasn’t anyone’s ‘sir’. He was just a man trying to save a dying river and, in the process, creating something the government hadn’t managed in years, about which he spoke exclusively to Indian Masterminds.

“NEWS REPORTS DON’T REVIVE RIVERS, PEOPLE DO”

A few months ago, the origin of the Betwa River — the lifeline of Bundelkhand — went dry. Newspapers wrote about it. TV anchors mentioned it. Everyone moved on. Except Dr. Paliwal and his associates, Dr. Suresh Garg, Prof. Arvind Diwedi, Retired IFS Officer Koshlendra Singh, and Mr. Parikshit Singh.

“Everywhere you look, rivers are dying. Everyone talks. No one acts,” he says. “We just decided — enough. Let’s do something.”

And so began one of India’s most audacious citizen-led environmental movements.

THE PLAN: 7 DAYS. 55 CHECK DAMS. 0 EXCUSES.

The idea was wild. Build dozens of check dams at the river’s origin in the last week of May, during Nautapa, the hottest stretch of the year. Not with machines. With volunteers.

“This kind of work usually happens before summer,” Paliwal shares. “But real efforts aren’t made in comfort. We chose the hardest week to show it can be done.”

The plan was hatched by the Betwa River Study and Public Awareness Group, founded by Paliwal after retirement. Over the past three years, they’d been warning the state about the Betwa’s decline. They even walked 200 kilometers along its banks in 2023, speaking to villagers and school kids in every kasba.

“We weren’t collecting data. We were sowing seeds of awareness,” he shared with Indian Masterminds.

When the government delayed action, the group chose action.

MAY 25, DAY 1: FROM 12 PEOPLE TO A RIVER ARMY

It began modestly. On May 25, just 12 people showed up. Two core members, Arvind Dwivedi and Vinod Pateriya, camped overnight in Jhiri. The first to respond weren’t activists — they were children, curious and eager.

Two check dams were built that day. The next day? Three more. And then, the spark caught fire. Newspapers picked up the story. Messages poured in. Groups arrived from Indore, Harda, Betul, and Ganj Basoda.

Some came for a day. Others stayed the whole week. People took leave from work, families joined, and students showed up with backpacks and spades.

“We thought we’d make 20. We made 55,” Paliwal says, eyes wide with disbelief. “In seven days. In 47°C heat.”

A MOVEMENT, NOT A PROTEST

This wasn’t a dharna. It wasn’t a campaign with hashtags. It was a movement of feet on the ground, hands in the dirt, and hearts aligned with purpose.

While the state government built three check dams in three months, this volunteer group built 55 in one week — all by hand.

“We didn’t blame anyone. We just led by doing,” Paliwal says. “And people followed.”

IT’S NOT JUST ABOUT THE DAMS

The check dams were just the beginning. The group has laid out a three-step action plan to revive the Betwa for good:

- No Tree Cutting Around the Source

Forests preserve water. Deforestation near the origin will kill the river faster than any summer ever could. - Water Harvesting Through Hillside Dams

More check dams will be built in the surrounding hillocks to capture rainwater and recharge groundwater. - Shift from Water-Guzzling Crops to Fruit Orchards

Farmers will be encouraged to grow mango, guava, jackfruit, and lemon, instead of wheat and moong, to reduce groundwater strain and increase green cover.

NEXT PHASE: PLANTING SAPLINGS, PLANTING HOPE

In June–July 2025, the group will distribute 10 fruit saplings per family to those living around the Betwa’s source. Cost: ₹1,100 per family. Many volunteers are sponsoring entire families.

“We want everyone to own a tree. When you plant something, you protect it,” says Paliwal. “And what better gift than fruit-bearing trees for future generations?”

Change has become contagious. As of June, schools, citizen groups, and village panchayats from across MP have reached out, asking: Can we do this in our area too?

FROM BHOPAL TO BETWA: A STORY THAT FLOWS

This isn’t just the story of one river. It’s the story of a retired officer who refused to retire from his responsibility. It’s about a group of people who didn’t wait for permission to care. It’s about children who picked up shovels because they were curious and became part of history.

And if the Betwa flows again this monsoon, it will carry more than water. It will carry the proof that when people come together, they can move mountains, build dams, and even wake a river from the dead.