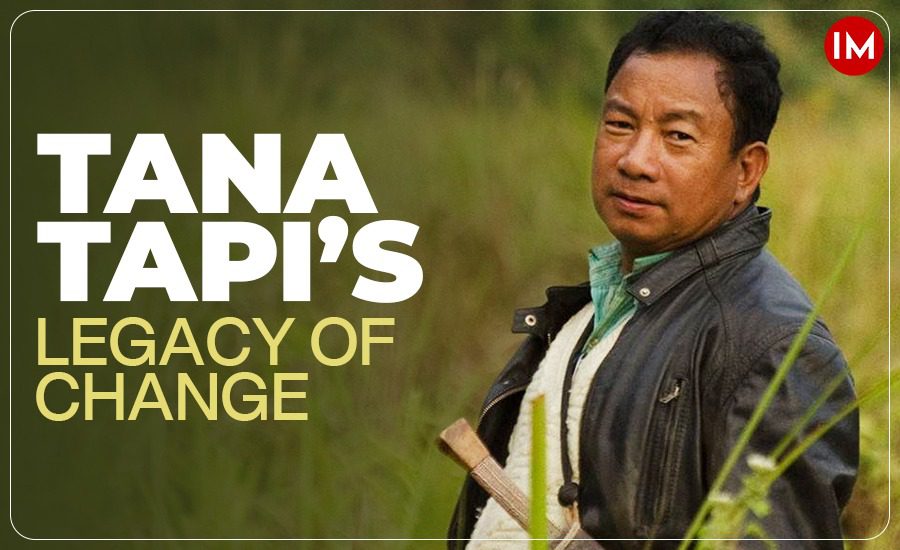

In the remote wilderness of Arunachal Pradesh, where survival often comes at the cost of nature, a man named Tana Tapi (Retired State Forest Officer) emerged as an unlikely hero. Faced with a forest teetering on the edge of destruction and communities deeply dependent on hunting and logging, he did what many thought was impossible. Over years of unwavering effort, Mr. Tapi not only restored the Pakke Tiger Reserve to its former glory but also transformed the lives of those who once saw the forest as their only means of survival.

This is the story of how one forest officer’s determination turned hunters into protectors, desperation into hope, and a threatened wilderness into a thriving sanctuary.

STEPPING INTO A CRISIS

When Tana Tapi took charge as the Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) of Pakke in 2004, the situation seemed dire. The Pakke Tiger Reserve, covering 862 square kilometres in the East Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh, was struggling with rampant poaching and illegal logging. The reserve, once home to a rich diversity of wildlife, was being depleted at an alarming rate. Elephants, tigers, pangolins, and hornbills were just a few of the species at risk of disappearing entirely. Hunting, once a traditional way of life for the local Nyishi community, had become the primary source of income, further aggravating the situation.

The forest infrastructure was in ruins: there was only one watch-tower and a handful of forest guards, and the area was nearly impossible to patrol effectively. Local villages had long been battling poverty, and the flood that washed away thousands of hectares of farmland only added to the desperation. The people of Pakke had few options left, and the forest, in their eyes, was a resource to be exploited for survival.

BUILDING INFRASTRUCTURE AND MANPOWER

Mr. Tapi understood that protecting the forest wasn’t just about stopping illegal activities—it was about offering the community something more sustainable and meaningful. His first step was to strengthen the physical infrastructure of the reserve. Under his leadership, the number of watchtowers increased from a single tower to 50. These watchtowers were crucial in monitoring the forest, preventing poaching, and providing forest guards with the necessary surveillance tools to protect wildlife. Mr. Tapi also expanded the network of patrolling roads, extending it from just 7 kilometres to 200 kilometres, allowing for better coverage and response to threats.

Tana Tapi also invested in human resources, recruiting local youth as forest guards. By involving those who once hunted the forest’s animals, he created a shift in perspective—transforming poachers into protectors. These new forest guards were trained to patrol the reserve, keep watch over the endangered species, and educate their communities about the importance of conservation.

TURNING HUNTERS INTO PROTECTORS

However, the real challenge for Tapi was changing the mindset of the local community. The Nyishi people, with their centuries-old hunting traditions, viewed the forest as an integral part of their livelihood. Mr. Tapi knew that if conservation was to succeed, it needed to align with the needs of the people. He began by meeting with the gaon buras—village elders who held significant influence within the community. The officer engaged them in conversations about the forest’s declining health and the potential benefits of preserving it.

The elders, once resistant to change, slowly warmed to the idea. With their support, Tana Tapi formed Ghora Aabhe (village fathers), a group of former hunters who were now employed as park protection officers. These men, who had once hunted the animals of Pakke for sustenance, became the guardians of the very creatures they had once threatened. He paid them from his own pocket initially, until they were formally employed by the reserve. This created a tangible incentive for the community to change.

Pakum Nabum, a key member of Ghora Aabhe, recalled how the group started imposing fines on those who killed animals within the reserve. “The fines, ranging from ₹2,000 to ₹5,000, were enough to make people think twice before killing animals. Over time, the pressure worked. Poaching became less frequent,” he said.

EMPOWERING WOMEN AS CONSERVATION PARTNERS

Mr. Tapi didn’t stop with the men. He recognised the importance of involving women in the conservation process, knowing they could be powerful agents of change within their families. To do this, he established 37 women’s self-help groups (SHGs) within the villages. These SHGs not only provided financial support to the families but also played an instrumental role in spreading conservation awareness.

The women became vocal advocates of preserving the forest, convincing their husbands and children to abandon hunting. The SHGs also offered small loans at low interest rates, empowering the women economically while contributing to the overall well-being of the community. The officer’s efforts helped create a sustainable model where both the forest and the people could thrive together.

A LEGACY OF EMPATHY AND LEADERSHIP

Mr. Tapi’s approach was not merely administrative; it was deeply empathetic. He understood the struggles of the people and treated them with respect and kindness. This was evident when forest guard Karo Tayem was killed by a wild elephant. Instead of merely offering condolences, he personally helped the family rebuild their home, destroyed by the same tusker. His compassion for his team extended beyond his professional role, earning him the affection and loyalty of those who worked under him.

His leadership, however, was not without challenges. In 2007, Mr. Tapi was transferred to the Mehao Wildlife Sanctuary in Lower Dibang Valley due to political pressures. The people of Pakke were devastated by his departure and protested vehemently. Their voices were heard, and in 2008, he was reinstated as the DFO of Pakke Tiger Reserve. He continued his work there for another seven years, overseeing the reserve’s transformation into a symbol of successful conservation.

Despite Mr. Tapi’s efforts, the people of the region continued facing challenges. With nearly 70% of the population living below the poverty line, many still rely on daily wage labour and government schemes like MGNREGA for survival. While Tapi’s contributions have ensured the protection of Pakke’s wildlife, the future of the reserve depends on continuing the work he began, especially in motivating younger generations to stay involved in conservation.

A LEGACY OF CHANGE

Tana Tapi’s retirement from the State Forest Service marks the end of an era for Pakke Tiger Reserve, but his legacy endures. Under his stewardship, the once-threatened reserve is now a thriving haven for wildlife. The local community, which once saw the forest as a resource to be exploited, has become its protector, with livelihoods centred around conservation rather than destruction. Tana Tapi’s journey proves that saving the environment and uplifting communities are not mutually exclusive—they can go hand in hand.

As the forest continues to hum with the sounds of life, the hornbills calling from the trees, and the elephants roaming free, Tana Tapi’s work lives on. For the people of Pakke, he was not just a forest officer. He was a man who changed their world—one they now see as a treasure worth preserving.