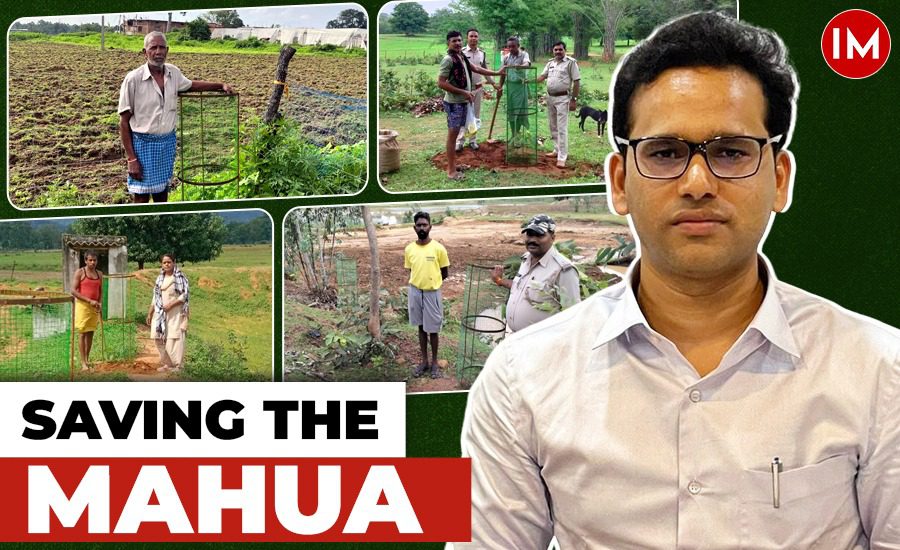

In a pioneering effort, IFS officer Manish Kashyap, the 2015 batch Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) of Manendragarh Forest Division, has spearheaded the first large-scale mahua tree preservation project in Chhattisgarh. The initiative addresses the declining mahua tree population, a vital resource for the tribal communities of Bastar and Surguja regions. These trees, known for their economic, religious, and social significance, have seen a sharp decline due to unsustainable harvesting practices and a lack of new saplings.

Speaking with Indian Masterminds, Mr. Kashyap shared about the initiative in detail.

The mahua tree, scientifically known as Madhuca longifolia, plays a crucial role in the livelihoods of the tribal communities, contributing significantly to their income. A single mature mahua tree can provide around ₹10,000 worth of produce annually, and with ten trees, a family can earn up to ₹1 lakh. However, the declining production of mahua flowers and seeds, coupled with the absence of younger trees, has raised concerns among the locals. “If we do not focus on regeneration, these trees, which have a lifespan of about 60 years, will soon vanish,” says DFO Manish Kashyap.

ADDRESSING THE CORE ISSUE

In many villages across Bastar and Surguja, one can easily spot large, old mahua trees standing alone in fields or barren lands, but smaller or medium-aged trees are rarely seen. The primary reason behind this is the traditional practice of clearing the ground by burning leaves before the mahua flower collection in the summer season. Unfortunately, this practice also destroys any young mahua saplings, resulting in almost zero natural regeneration outside the forest areas. Additionally, the complete collection of mahua seeds by locals prevents natural propagation, leading to a steady decline in tree numbers.

“The challenge is not the lack of mahua trees in the forest, but the absence of new saplings in the village outskirts and agricultural lands where most of the collection happens,” explains Mr. Kashyap. “Tribal communities prefer collecting mahua from trees outside the forest for ease of access, but without younger trees, their primary source of income is at risk.”

A COMMUNITY-CENTRIC APPROACH

Under Mr. Kashyap’s leadership, the initiative has planted 30,000 mahua saplings across forest areas, barren lands, and village outskirts, involving active community participation. “Planting these saplings with tree guards ensures their survival, as cattle tend to eat the young shoots otherwise,” the officer informed.

The project also included educational outreach, where forest staff visited villages to explain the importance of conserving mahua and encourage participation in the initiative. “We organized a large-scale Van Mahotsav in the village of Kachhor to kickstart the project, with around 2,000 to 3,000 villagers attending,” Mr. Kashyap recalls. This not only helped in spreading awareness but also motivated the locals to take an active role in preserving these trees.

SCALING UP

Despite the enthusiasm, the initiative faced several challenges, particularly in setting up the protective tree guards and securing adequate funding. “Initially, we had to arrange everything on our own, including the rapid construction of tree guards, as government schemes or departmental resources were limited,” says Mr. Kashyap. However, the community’s interest and willingness to provide land for planting helped overcome these initial hurdles.

“The residents were very receptive. Many even offered their land for planting saplings, understanding the long-term benefits for their families and future generations,” the officer further added. The project aims not only to regenerate Mahua populations but also to secure the economic stability of the communities that rely on them. By increasing the mahua tree population, future generations will continue to benefit from the trees’ products, including mahua flowers and seeds, which are sold to traders for various uses, including the production of traditional drinks and medicinal products.

INNOVATIONS IN MAHUA HARVESTING

One of the notable innovations introduced in this initiative is the promotion of a food-grade mahua collection, which involves using nets to catch flowers before they touch the ground, thus maintaining their purity and increasing their market value. “We implemented this new technique in a few forest divisions, including Manendragarh, collecting around 500 quintals of food-grade mahua this season,” says Mr. Kashyap. This method not only fetches a higher price—up to four to five times more than the traditional collection methods—but also ensures a cleaner product that meets the standards for use in the medicinal and food industries.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

With the initial success of planting 30,000 saplings, Mr. Kashyap and his team plan to scale up the initiative in the coming years. “Our goal is to plant up to 1 lakh or even 2 lakh saplings in the next phase,” he shares. The hope is that these efforts will significantly boost the mahua tree population, providing long-term economic benefits to the tribal communities and ensuring the sustainability of this essential resource.

IFS Manish Kashyap’s mahua conservation initiative is a step towards preserving not just trees but a way of life deeply intertwined with the cultural and economic fabric of Chhattisgarh’s tribal regions. “It’s not just about planting trees,” says Mr. Kashyap, “it’s about securing the future of these communities by ensuring that the mahua tree remains a lifeline for generations to come.”