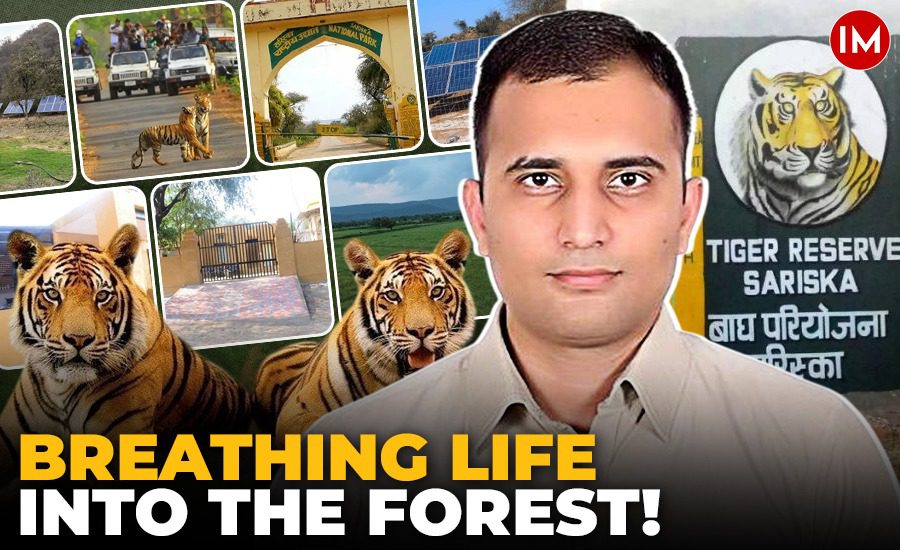

Sariska Tiger Reserve, nestled in the Aravalli hills of Rajasthan, once witnessed a grim chapter in wildlife conservation. In 2005, its tiger population had plummeted to zero, shocking the nation and prompting massive conservation efforts.

Today, the story is remarkably different – and much of the credit goes to the dedication and dynamic leadership of Abhimanyu Saharan, a 2017 batch Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer currently serving as the Deputy Conservator of Forests (DCF) and Deputy Field Director at the reserve.

Under his watchful eye and committed direction, Sariska has witnessed not just the resurgence of tiger numbers to 48, but also significant ecological and technological advancements that make it a model for other reserves across India.

Indian Masterminds interacted with Mr Saharan to learn more about his initiatives for the well-being of Sariska Forest and its wildlife, and how he helped the forest thrive and the tiger population grow.

Bringing Tigers Home: A Mission of Precision

Tiger conservation is not just about numbers – it’s about protecting territories, ensuring habitat safety, and responding swiftly to threats. In recent years, multiple tigers had strayed outside the protected zone. But thanks to efficient monitoring and tracking mechanisms implemented by Saharan, the animals were safely brought back.

“Tigers like ST-2303 reached as far as Jhabua in Haryana, ST-2402 moved to Mahukhurd in Dausa district, and ST-2305 also strayed out. All were retrieved with minimal stress to the animals, thanks to our team’s quick and careful response,” Mr Saharan explains.

These recoveries weren’t mere chance – they were the result of sustained surveillance networks, rapid response units, and a deep understanding of tiger behaviour.

Strengthening the Core: Infrastructure and Staff Empowerment

Sariska isn’t just home to wildlife – it is also home to numerous villages, which creates unique conservation challenges. Forest degradation, human-wildlife conflict, and staff shortages had long plagued the reserve. But Saharan approached the issue head-on.

“Earlier, we had limited staff and no proper establishments for them inside the reserve. Now, with new recruitments, we’ve created a network of anti-poaching camps that have had a visible impact,” he shares.

From constructing residential facilities powered by solar energy to ensuring clean water supply through borewells, the officer focused on providing basic but critical amenities to the frontline staff.

“Without light, water, and basic comfort, it’s tough to expect our young recruits to stay deep inside the forest. But now, they’re staying – and just by being there, they’re covering 5–10 sq. km each. That’s how our protection net has strengthened,” he adds.

Healing the Habitat: Grasslands, Weeds, and Water

The officer also undertook the restoration of degraded grasslands, a vital move to improve the habitat for herbivores – which in turn supports the growing tiger population.

Saharan and his team eradicated invasive weeds like prosopis juliflora, lantana, and parthenium that had overwhelmed native species due to overgrazing and human disturbance. With a focus on endemic grass species, nurseries were developed to aid in grassland regeneration.

“As the grasslands recover, herbivores don’t need to migrate far for food. That stabilizes their populations – and supports tiger expansion,” he notes.

Water, always a precious commodity in Rajasthan, was another core focus. Solar-powered borewells were installed every 5–10 km, ensuring that both predators and prey didn’t need to migrate extensively during the dry season.

“By shrinking their territories slightly through reliable water points, we’ve made room for more tigers. That’s why we’ve gone beyond our expected carrying capacity of 20, and now have 48 tigers thriving,” IFS Saharan explains.

Tackling Tourism and Human Disturbance

The Pandupol temple, located deep inside the reserve, attracts thousands of visitors. While religious tourism boosts footfall, it also brings disturbance and unwanted feeding of wildlife. The officer has taken firm steps to control this.

“People mean well, but feeding wild animals disturbs their natural instincts. We’ve already limited such practices, and now we’re planning to phase out private vehicles. Only government-run buses will be allowed to minimize stoppages and littering,” he states.

Moreover, the main tourist zone, once neglected, is undergoing a transformation. A new interactive interpretation centre is being developed to enhance the experience even if tiger sightings remain elusive.

“Sariska is a valley; it’s not flat like Ranthambore. So, even if tigers aren’t spotted, tourists should still leave enriched,” says Saharan, highlighting his balanced approach to eco-tourism.

Modern Monitoring: From Foot Patrols to AI

Understanding that technology is the future of conservation, Saharan has spearheaded initiatives to build a 100–150 km network of patrol routes, improving night patrolling and accessibility to remote areas. But more impressively, Sariska is on the verge of a tech leap.

In collaboration with IIT Delhi and Google, his team has developed a prototype for AI-based tiger identification using camera traps.

“This will revolutionize wildlife monitoring. With this system, we can identify individual tigers, understand territory usage, and even recognize other species. The goal is to move towards a technology-driven conservation model,” IFS Saharan shares.

The Road Ahead: Expansion and Vision

The journey doesn’t end with Sariska. The officer is now pushing for the expansion of the CSRSCA (Critical Tiger Habitat) by integrating 600 sq. km of adjoining territorial forest into the reserve’s buffer area.

“If this area is added, Sariska could potentially support up to 100 tigers. That’s the future we’re planning for,” he says with conviction.

This vision goes beyond numbers. It reflects a holistic, sustainable, and science-backed model of conservation – something other reserves can replicate.

A Forest Restored, A Future Secured

From zero tigers in 2005 to a thriving, protected population of 48 today, Sariska Tiger Reserve is a shining example of what strong leadership, community involvement, habitat restoration, and smart technology can achieve.

And at the heart of this transformation stands IFS Officer Abhimanyu Saharan – a dedicated, thoughtful, and forward-looking forest officer who is quietly but powerfully changing the landscape of Indian wildlife conservation.

“The resilience of the system, the involvement of the people, and the commitment of our team – it’s all coming together now. The forests are coming alive again,” he says, looking toward the future.