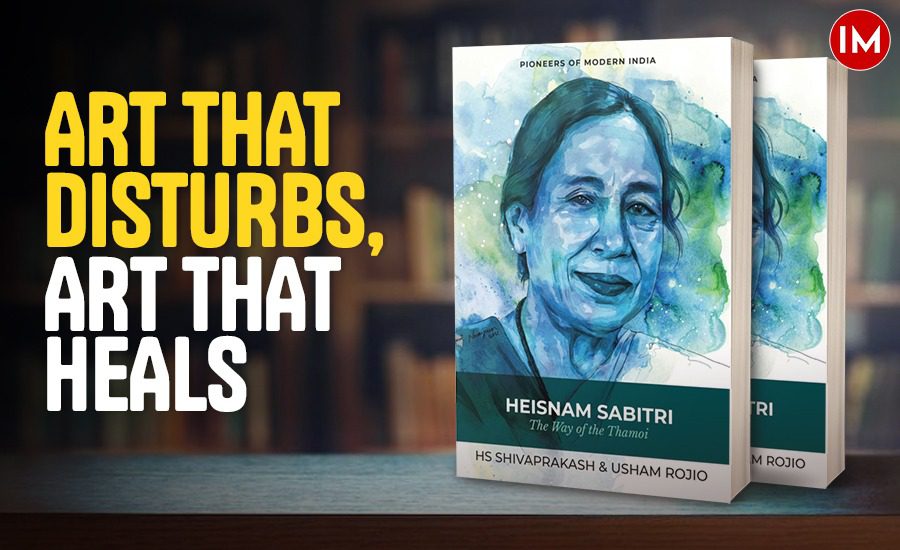

Art should comfort the disturbed, and disturb the comfortable — the artist and the audience together shape the lived legacy of the art. In the theatre traditions of contemporary India, this complex weight finds balance through the remarkable work of Padma Shri Heisnam Sabitri. “Had Sabitri-Kanhailal’s theatre become a model for Indian theatre at large, the annals of modern Indian theatre would have been very different,” write the authors of this biography, which – especially now when theatre seems to have become such a rare light – could perhaps be extended as a thought experiment to the general spirit of art and audience in India.

Born in Mayang Imphal in 1946, Sabitri grew up performing her Meitei family’s Vaishnava bhakti mandap theatre and bashok singing. Her aunt Gouramani Devi was an established theatre artiste through whom she was introduced to stage acting, which at the time was influenced by the drama of popular Hindi films and the critical consciousness of Bengali theatre. In the 1960s, she met Heisnam Kanhailal, the man with whom she would build a marriage and an entirely new methodology of theatre.

Sabitri-Kanhailal’s process drew from the physical culture and performance folklore of Manipur as much as from an observation of the natural world. The “Theatre of the Earth” which they produced was deeply sensitive to and in conscious harmony with their environments. A consistent focus was on sorgi kanglon (breathing dynamics) and hakchanggi kanglon (body dynamics) as lived and performed meditation. The richness of this process was in its continuous observation of the self; resulting psychophysical insights were channeled into creative expression. The aim for Sabitri as an actor-performer was to merge intellectual awareness and physical awareness, to dissolve the line of communication between the inside and the outside. Their emphasis on breathwork and non-verbal dramaturgy held potential for universal understanding as well. Words were used sparingly. Meaning was conveyed through body language instead.

The soundscape of Sabitri-Kanhailal’s first experimental production Tamnalai (1972) was a haunting song spontaneously composed by her upon his request: at the dawn of the Kabui tribe’s Gang-ngai festival, in response to the vibrative echoes of ritual lamlenlu and the crying of a dog, while she was breastfeeding their child. As Sabitri said in an interview with the authors included in the last section of this book, “See, we started delivering dialogues, musically, like in a wave, like singing… There is rhythm in tune with breathing in speech. That is also music.”

In this play, and many others which they would produce, Sabitri was the Mother. “The role of a mother figure was a leitmotif that ran across many productions, not simply of Kanhailal, but of others as well, staged during the decade of the 1970s. The performances were replete with different body movements, compositions made of one single body or multiple bodies organized to form an idea or a concrete thing like a prop.” Very little was spent on any instruments other than the voice and the body. In their practice of community theatre, people around them became integral actors within the plays. Nupi Lan in 1978, based on the 1939 Women’s War in Manipur, was an open-air production involving around a hundred women from Imphal’s women’s market. Sanjanneha in 1979 was acted out by the villagers of Umathel. Several of Sabitri-Kanhailal’s genre-bending productions were ideated, on instinct, and performed together with an audience which was not solely witness but also active collaborator. Theirs was a participative catharsis in which the spectator does not merely watch, but is to be healed and thus transformed.

This work in meaningful theatre was not geared towards or marked out for commercial support. A grant from the Ford Foundation in the 1980s and occasional help from national networks brought some financial relief to Sabitri-Kanhailal, enabling their study of theatre methodology drawn from greats like Badal Sircar and Eugenio Barba alongside immersion into traditional folk forms like the operatic Moirang Parva. Inspiration from every source was innovated into their own contexts and capacities. In the 1990s, they adapted the film script of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon into a play which they eventually took to Karnataka to perform in Kannada with the Rangayana theatre group.

The Mahabharat had already been a theme – with Karna in 1997 – before it shaped their most recognizable work in an adaptation of Mahashweta Devi’s Draupadi in 2000: “Sabitri felt Dopdi Mejhen’s story was her story, and that of numerous Manipuri women, who continued to be witness to and victims of relentless brutality and sexual violence.” The play had to be shut down after four shows due to vociferous criticism around the final scene in which Sabitri – as Dopdi – bares herself against an Indian army officer’s sexual violence. Four years later, this scene from the play was replicated in real life, when 12 Manipuri mothers staged a nude protest against the rape and extrajudicial murder of Thangjam Manorama by the Indian Army under AFSPA.

Sabitri-Kanhailal addressed critics with two other self-evident plays in the same year: Ezzat (Honour) and Nupi (Woman). Through the millennial decade, they continued to conduct workshops, expand their performance practices to the general North East, and foster the theatre festival ‘Under the Sal Tree’ in Rampur (whose venue is now locally known as the Macbeth Jungle in homage to the Shakespearean tragedy with which Heisnam Kanhailal had wanted to inaugurate the space.)

Professor HS Shiva Prakash and theatre scholar Usham Rojio combine academic insight and personal knowledge into this fine portrait of modern Indian theatre. An admiration of Heisnam Sabritri’s artistry suffuses the book’s contextual explanation of precisely why her improvised poetic theatre is so exceptional. Professor Shiva Prakash’s familiarity with Kanhailal is a particularly rich undercurrent. “Though Kanhailal did not speak much about Natya Shastra theatre, unlike his better-known contemporary Kavalam, Sabitri-Kanhailal theatre was very successful in arousing rasa in the hearts of spectator-participants.”

‘Thamoi’ means ‘heart’. ‘Thawai’ is ‘soul / life’. ‘Amaibi’ is the trance state of possession which reveals itself to priestesses. In her interview with the authors, Sabitri says: “Actually, I don’t have any amaibi-like quality. I am not an amaibi. But I observe them closely. For example, when they do yakeiba (invocation of God), they begin building up tempo with the help of a bell. It is not only the invocation of God, but they invoke their body as well, in order to attain a state… Then they get the ehool (impulse). They have some extraordinary shakti. Whether their prophecy is right or wrong is a different thing. But I study their processes and observe how they connect with us. I don’t know whether I am making sense or not… I don’t know my qualities. I only open up my heart (thamoi) and play.”