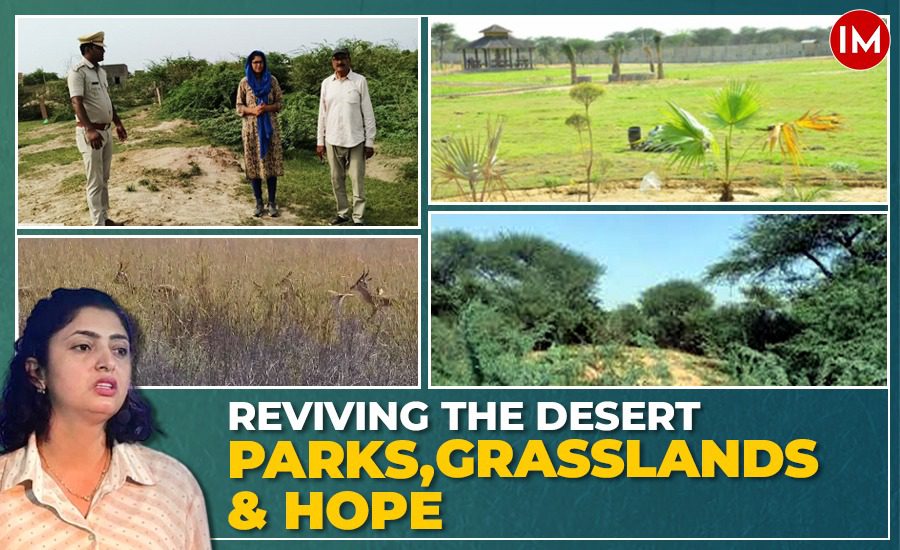

In the harsh and dry expanse of Rajasthan’s Churu and Barmer districts – areas largely devoid of natural water bodies or green spaces – 2013 batch Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer of Rajasthan cadre, Ms Savita Dahiya undertook a task most deemed impossible: turning degraded, encroached, garbage-laden lands into lush parks, eco-tourism zones, and revived grasslands that now support thousands of people and wildlife alike.

Her journey was not just a story of ecological restoration, but also one of personal resilience, bureaucratic negotiation, and public collaboration – often carried out under immense pressure, while she was pregnant, battling health issues, and politically targeted.

Indian Masterminds interacted with IFS Dahiya, now DCF Barmer, to learn more about the green transformation of the desert district. “With a supportive team, everything became possible,” she shared. “It’s our team’s dedication and hard work that made this transformation happen. We stood by each other through resistance, court cases, and logistical hurdles – and the results speak for themselves.”

Phase 1: Transforming Garbage Dumps into Nagar Vans and Herbal Parks

When Ms Dahiya was posted in Churu, she found most forest patches around the city had become illegal parking lots, waste dumping grounds, and encroached market spaces.

“There were no green spaces… just concrete jungles, stray dogs, garbage heaps, and trucks. It was heartbreaking to see people living without access to even a small park,” she said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms Dahiya saw an opportunity: with reduced public movement and administrative focus elsewhere, she mobilized her limited staff, removed encroachments, and got cases filed where needed – even as she was pregnant with her second child.

With just a few months remaining before her delivery, she, along with her team, used the pandemic-induced silence to clean up the mess. Illegal structures were removed, proposals were swiftly sent to the Government of India, and approvals were secured in record time.

This resulted in the creation of:

- 3 Nagar Vans (Urban Forests)

- 2 Luv Kush Vatikas

- 1 Medicinal Park

- 2 Green Lungs

These were funded via NREGA, MLALAD, central funds, and state budget announcements, and now offer walking tracks, yoga gardens, open-air clubs, children’s play areas, and even water bodies in areas previously considered lost to urban decay.

Read Also: Nature’s Guide & Birds Watchers Training in Tal Chhapar Sanctury of Churu

Taranagar Herbal Park: A Community-Powered Miracle

One standout success is the Taranagar Herbal Park, built using 93% NREGA funds, with additional support from a socially motivated retiring forester and the local MLA.

“There was no budget, but we made it work. Fencing was done under NREGA. The MLA gave funds for tiles and entrance gates. Locals installed benches in memory of loved ones. Everyone came together,” Ms Dahiya added.

The park now hosts 27 varieties of medicinal plants, walking tracks, and a small herbal nursery. It draws around 5,200 weekly visitors and was nominated by the District Magistrate of Churu for the CM Excellence Award.

Phase 2: Reviving Rajasthan’s Traditional Grasslands

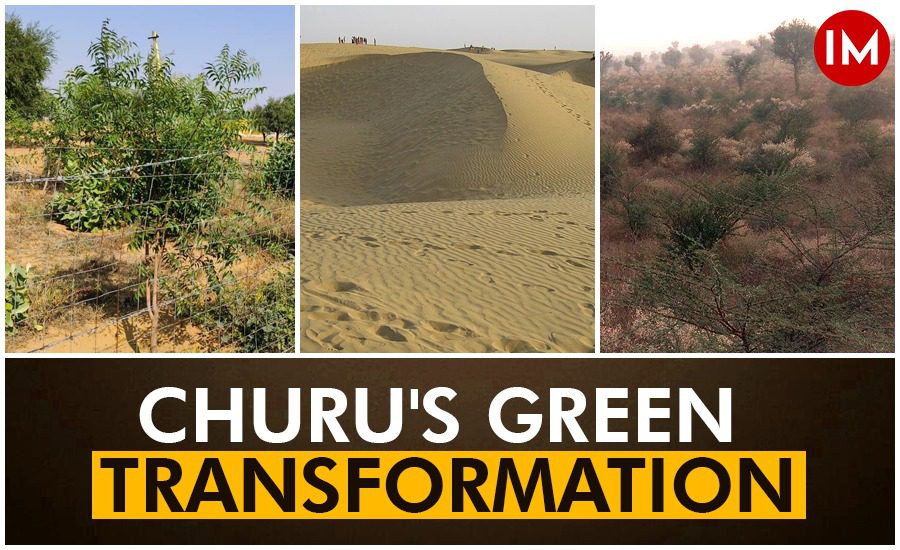

After her transfer to Barmer, Dahiya turned her attention to desert grassland restoration – reclaiming over 1,100 hectares of degraded wastelands overrun with Prosopis juliflora, a highly invasive species.

Satellite Sanctuary for Tal Chhapar’s Overflowing Blackbucks

The most ambitious project was the Jaswantgarh Grassland, created as a satellite sanctuary to relocate Blackbucks and Chinkaras from the overburdened Tal Chhapar Sanctuary.

“The blackbucks were in danger due to overcrowding. A PIL was also filed in the Jodhpur High Court regarding this. Eventually, the court ordered their relocation, and revenue land was handed over to the Forest Department,” she explained.

In just two years, the swampy, saline, weed-infested area was converted into a self-sustaining grassland featuring:

- Native grasses like Mothiya, Dhaman, and Daab

- Water bunds to stop contamination

- Fencing and seeding via seed balls and machines

This work is now being documented in a research paper and is seen as a model for desert grassland rejuvenation in India.

Read More: A Desert District’s Story Of Survival

Fighting Opposition, Misogyny, and Personal Struggles

While the green projects bloomed, Dahiya faced relentless challenges: political opposition, departmental resistance, and personal threats.

Sources in the department said that while she was working on this project, people threw stones at her home and even cut off the electricity in an attempt to intimidate her. Despite repeated efforts to derail the mission, she and her team remained undeterred.

Despite being hospitalised for pre-term delivery due to COVID, Ms Dahiya continued supervising work remotely from Jaipur.

“Even while on maternity leave, I continued to monitor the progress. When people send me photos of children playing, women doing yoga, and elders sitting under trees – my team and I know we did the right thing,” she said, emotionally.

Recognition and Long-Term Impact

Today, the eco-tourism sites in Churu and the revived grasslands in Barmer are being replicated across Rajasthan. Collectors and MLAs frequently request similar projects for their constituencies.

Even opposition leaders acknowledged the value of her work. The sites have hosted political rallies, community picnics, and environment awareness drives. NREGA teams now cite these parks as success stories in fund utilization.

“This wasn’t just afforestation – it was about giving people dignity, space to breathe, and nature they could access daily,” Ms Dahiya noted.

More Than Just a Forest Officer

From clearing garbage dumps during a pandemic, to winning legal battles for wildlife, to creating green lungs in the Thar Desert – IFS Dahiya has not just protected the environment, but actively redefined what urban-forest integration can look like in India.

Her story is a powerful reminder that real transformation begins with courage, collaboration, and a refusal to give up, even when the odds – and the system – are against you.

“In the desert, I created green patches. But in the system, I created space – for honest work to be respected. That’s what I’ll always cherish.”