The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) had taken some urgent steps to bring the errant Indigo Airlines operations v in track. It ordered the airline to scale down its winter schedule, align operations strictly with available crew strength, and submit daily reports on cancellations, crew availability and passenger refunds.

The Civil Aviation Ministry went a step further by setting up a special oversight team to monitor IndiGo’s operations, an extraordinary move for an airline that commands nearly 65 percent of India’s domestic market.

The Delhi High Court, hearing a public interest petition, questioned how the situation had been allowed to deteriorate despite clear warnings on pilot fatigue rules. It asked pointedly whether safety had been compromised in pursuit of expansion and whether regulatory leniency had encouraged operational excesses.

This was not merely about cancellations. It was about systemic stress in India’s aviation model coming into the open — with IndiGo as its most visible example. Can IndiGo follow the route taken previously by other reputed airlines like Jet Air and Kingfisher? If not, then how is its case different from others?

WHY INDIGO MATTERS MORE?

IndiGo is not a marginal airline. It is the backbone of India’s domestic air travel network, carrying more passengers than all its competitors combined. Any disruption in its operations immediately affects fares, connectivity and consumer confidence across the country.

But this operational crisis is only the surface. Beneath it lies a deeper story about why airline businesses in India remain high-risk ventures, regardless of market share or brand strength.

HISTORY OF FAILURES

Over the past one to one-and-a-half decades, India has seen several airlines shut down, highlighting the structural vulnerabilities of the country’s aviation sector. Each collapse tells a story of financial stress, operational challenges and policy constraints that make airline operations in India particularly risky.

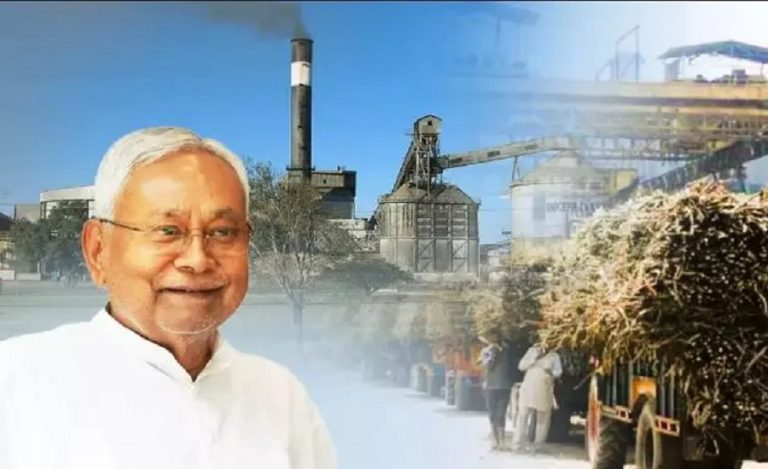

Jet Airways, which ceased operations in 2019, was once India’s largest private airline and a symbol of premium air travel. Its downfall was driven by mounting debt, rising fuel costs and intense competition from both domestic and international carriers. Disputes among promoters weakened leadership at a critical time, while the lack of timely financial support from banks pushed the airline into a severe cash crunch. Poorly planned expansion and high fixed costs eventually made revival impossible.

Kingfisher Airlines shut down in 2012 after years of financial turmoil. The airline pursued aggressive and poorly thought-out expansion without a sustainable revenue model. Heavy borrowing, unpaid dues to oil companies and airports, and prolonged delays in paying employee salaries eroded confidence among lenders and regulators. Kingfisher positioned itself as a luxury airline, but the “high cost, low profitability” model proved unsustainable in India’s price-sensitive market.

Air India’s regional operations, earlier known partly under Alliance Air, were gradually shut down or merged during restructuring after 2022. These regional units consistently incurred operational losses due to ageing aircraft, high maintenance costs and low passenger demand on several routes. While the Air India brand continues, many loss-making regional operations were discontinued to streamline the airline.

OTHER EXAMPLES

Paramount Airways, which stopped flying in 2010, had carved out a niche in southern India with a focused business travel model. However, legal disputes related to aircraft leasing led to the grounding of its fleet. Limited route presence and insufficient capital meant the airline could not survive prolonged operational disruption.

Air Costa, which ceased operations in 2017, struggled primarily due to financial stress. The airline operated Embraer aircraft, whose maintenance and operational costs were relatively high for a small regional carrier. As funding dried up and investors pulled back, Air Costa was unable to sustain its operations.

Air Pegasus shut down in 2016 after facing severe cash flow problems. The airline was unable to pay pilots and engineers on time, while rising operational costs and low passenger volumes on regional routes made the business unviable. The lack of scale and consistent demand ultimately forced it to stop flying.

SPICEJET & GOAIR

SpiceJet has not shut down completely, but it has repeatedly come close to collapse, particularly in 2014 and again around 2023. The airline has faced persistent liquidity shortages, mounting dues to fuel suppliers, and the return of leased aircraft due to non-payment. Keeping fares artificially low to stay competitive further strained its finances. While SpiceJet continues to operate, it remains in a fragile financial position.

Go First, earlier known as GoAir, ceased operations in 2023 after a combination of technical and financial crises. A large portion of its fleet was grounded due to engine supply issues, severely impacting capacity and revenue. At the same time, rising debt, intense competition in the low-cost carrier segment and a sharp cash crunch made continued operations impossible. The airline’s collapse highlighted how technical disruptions can quickly spiral into full-blown financial failure.

The common thread in all these cases was not the lack of passengers. It was structural fragility — thin margins, volatile costs and heavy dependence on external factors beyond an airline’s control.

THE ECONOMICS

Airlines in India operate on razor-thin profit margins, typically in the range of 3 to 5 percent in good years. Even a small shock can turn profits into losses.

Fuel is the biggest vulnerability. Aviation turbine fuel (ATF) accounts for up to 40 percent of operating costs and is heavily taxed. In 2022, ATF prices were already elevated, but today they are significantly higher in rupee terms due to a combination of global oil trends and a weaker rupee.

WEAK DOLLAR HURTS

With rupee depreciates fast against the dollar – being at its lowest ebb historically, having crossed the 90 rupee mark, airlines pay more not only for fuel but also for aircraft leases, engine maintenance and spare parts — most of which are dollar-denominated.

This currency risk hit IndiGo hard in recent quarters. Despite healthy passenger demand and strong revenues, foreign exchange losses pushed the airline into a quarterly loss. This is a classic Indian aviation paradox: planes are full, but balance sheets bleed.

INDIGO BALANCE SHEET

IndiGo remains financially stronger than most of its peers. It has sizeable cash reserves, a largely young fleet and disciplined cost controls. Its revenue has continued to grow, and it has historically generated operating profits even in difficult periods.

However, recent numbers show pressure building. Rising fuel costs, higher maintenance expenses as aircraft age, increasing airport charges and crew costs have all contributed to margin compression. The pilot shortage crisis has added a new dimension: regulatory compliance is now directly constraining revenue growth.

Unlike Kingfisher, IndiGo is not drowning in debt. Unlike Jet Airways, it has not lost strategic direction. But the lesson from history is clear — scale alone does not guarantee survival.

INDIGO IS NOT KINGFISHER

There are critical differences. IndiGo’s business model is fundamentally conservative. It avoids luxury frills, sticks to a largely single-type fleet and maintains operational discipline. It has not expanded recklessly into loss-making long-haul routes without preparation, nor has it relied excessively on borrowed money.

Most importantly, IndiGo still enjoys the confidence of lessors, lenders and passengers — an asset Kingfisher and Jet lost long before they collapsed.

Yet confidence is fragile. Repeated cancellations, fare spikes during disruptions and regulatory censure can erode trust faster than financial losses.

CAN INDIGO SURVIVE?

The immediate priority is manpower correction. IndiGo must recruit and train pilots at a pace that matches fleet expansion, not trails it. Temporary measures such as expatriate pilots may buy time, but long-term stability requires sustained investment in training infrastructure and realistic scheduling.

Second, the airline must recalibrate growth. Chasing market share through aggressive scheduling while operating at the edge of regulatory limits is no longer viable. Sustainable growth will require fewer flights per aircraft, higher buffers and acceptance of slightly lower short-term profits.

Third, regulatory consistency matters. The DGCA must enforce rules uniformly across airlines, without exemptions that encourage risk-taking. At the same time, the government can ease systemic pressure by rationalising taxes on ATF and improving airport cost structures.

Finally, IndiGo must restore passenger confidence through transparency, timely refunds and predictable operations. In aviation, reputation is as valuable as aircraft.

CAUTION AHEAD

IndiGo’s turbulence is not an isolated corporate crisis. It is a reminder that Indian aviation remains a high-wire act, where growth, regulation and economics must remain in delicate balance. The collapse of past airlines shows what happens when that balance is lost.

IndiGo still has time, resources and credibility on its side. Whether it can emerge stronger from this episode will depend on how seriously it treats the warning — not just from regulators and courts, but from the industry’s own troubled history.

Referring to the surge in the Indian aviation sector, the Civil Aviation Minister Mr Ram Mivan Naidu recently said that there was enough space for five new airlines. But, when therebis existential crisis for the established airlines, how do new airlines be able to set base and work?