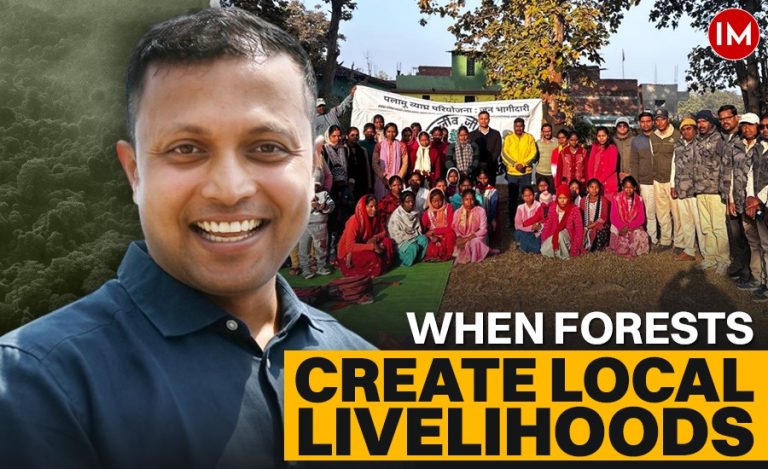

In this second part of the interview with Indian Masterminds, IRAS officer Ananth Rupanagudi offers a candid perspective on the Indian bureaucracy, tackling the pervasive stereotypes of corruption and inefficiency while highlighting the complexities of public service. With decades of experience in the Indian Railways, Rupanangudi addresses the public’s perception of bureaucrats as privileged and inactive, revealing a reality far more nuanced than social media narratives suggest.

WATCH THE INTERVIEW HERE-

Mr Rupanangudi acknowledges that corruption exists within the bureaucracy, a sentiment echoed by ordinary citizens who have encountered it firsthand. However, he emphasises that the issue is often exaggerated. “There’s a substantial amount of misperception,” he notes, reflecting on his own initial biases before joining the civil services.

He distinguishes between two critical dimensions of integrity: moral integrity, which involves resisting financial temptations, and professional integrity, which demands diligent work and decision-making to deliver on governmental promises. While moral integrity is non-negotiable, Mr Rupanangudi argues that professional integrity—working hard and adding value to public service—is equally vital but often overlooked.

Drawing from personal anecdotes, Mr Rupanangudi shares a story of his great-grandfather, a sub-magistrate, who requested a transfer to avoid a potential conflict of interest when his son began a legal practice in the same town. This legacy of moral fibre underscores the values Mr Rupanangudi strives to uphold, resisting temptations that he admits are prevalent in public service. He stresses that technology, such as online ticketing systems and faceless assessments in the IRAS, is a powerful tool to curb corruption by minimising human interaction.

Addressing public complaints about dirty railway coaches and infrastructure, Ananth Rupanangudi calls for shared responsibility. While acknowledging that the railways must improve trash disposal and maintenance, he urges passengers to adopt responsible civic habits, like using trash bags, to support cleaner trains. “It’s both ways,” he says, emphasising collaboration between citizens and the administration.

Mr Rupanangudi’s insights challenge the oversimplified narrative of a corrupt and lethargic bureaucracy. He advocates for systemic reforms, technological integration, and a cultural shift toward value-driven education to foster integrity. His reflections reveal a bureaucracy striving for efficiency amid societal pressures, offering a hopeful vision for a more accountable public service.