The first warning came on a Friday evening last week.

As dusk settled over Gangpur village in Bokaro’s Gomia block, a herd of elephants emerged from the darkness around 8.15 pm. Within minutes, panic ripped through the settlement. Somar Sao (50) and his five-year-old grandson Aman Kumar were trampled to death as they tried to escape. Three others, Rashi Kumari (11), Rahul Kumar (7), and Shanti Devi (60), were crushed and left fighting for their lives.

The village had barely begun to process the loss when the nightmare returned.

On Thursday night this week, the same herd struck again—this time in Gondwar village of Hazaribagh. While families slept, elephants pushed through walls and narrow lanes, turning homes into death traps. Six people were killed inside their houses. The dead included young parents, elderly residents, and the most defenceless of all: Anurag Ram, just one year old, and three-month-old Sanjana Kumari.

In the span of a few terrifying days, entire families were wiped out. The death toll climbed rapidly, and forest officials later confirmed what villagers already feared: this was not an isolated incident. The same herd had killed two people earlier in January as well.

What unfolded across Bokaro and Hazaribagh was not just a series of attacks; it was a chilling reminder of how suddenly fear can cross from the forest into the heart of a sleeping village.

“THIS IS NOT NORMAL ELEPHANT BEHAVIOUR”

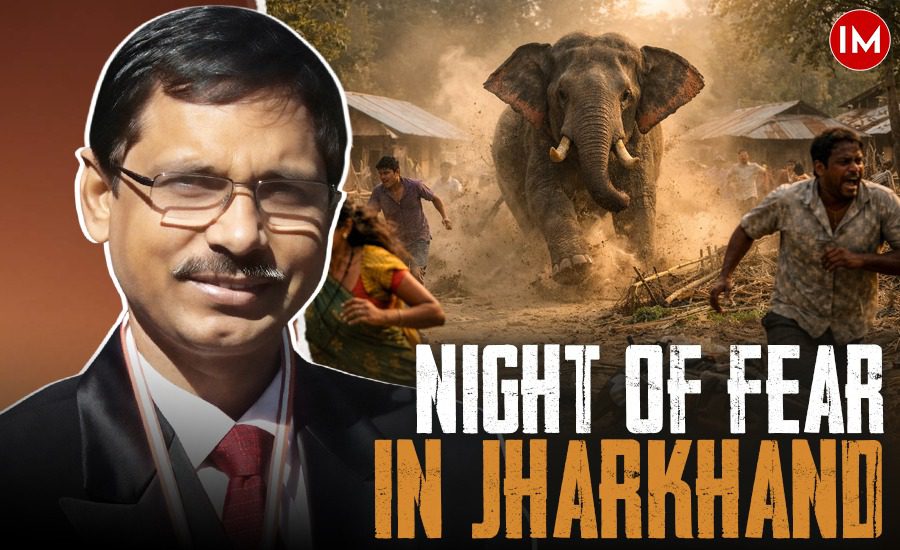

At the centre of the response stands IFS officer Sanjeev Kumar, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests of Jharkhand. Calm but candid, he is clear that what the state is witnessing is not routine.

“This is not regular elephant behaviour. It is very exceptional. Something has changed in the behaviour of a few elephants, especially those that have broken away from the herd,” he shared in an exclusive conversation with Indian Masterminds.

According to Kumar, much of the recent violence can be traced to a single herd of five elephants, one adult female and others moving closely around her. Forest teams believe the female may have been attacked or traumatised earlier, making the group unusually aggressive.

“When a female elephant feels threatened, the herd becomes extremely sensitive. Anyone outside their homes at night becomes vulnerable,” he explains.

FRAGMENTED FORESTS, CROWDED PATHS

Jharkhand lies along key elephant migration routes. These animals are not static; they need to move, sometimes 10 to 15 hours a day, across large forested landscapes.

But those landscapes no longer exist as they once did.

“Elephants are migratory animals. They need uninterrupted forests,” Kumar says. “Today, in two-and-a-half hours of movement, they hit a village, then another village. This fragmentation is a major trigger.”

Shrinking forests, blocked corridors, mining belts, and expanding settlements have forced elephants into repeated contact with people. Each encounter raises stress levels, on both sides.

DARKNESS, NOISE AND HUMAN PROVOCATION

Power cuts and pitch-dark villages add another layer of risk. In one earlier incident, villagers tried to drive an elephant away using flashlight beams. Instead of retreating, the animal charged.

Crowds chasing elephants, shouting, filming on mobile phones, all of it matters.

“When a herd wants to move peacefully and people surround them, shout, or take photographs, it irritates the elephants,” Kumar says. “That irritation can turn fatal.”

WHY TECHNOLOGY ALONE ISN’T ENOUGH

Jharkhand has quick response teams, drones, radio-collaring, and alert systems. Yet deaths continue.

Kumar explains why the pattern can be misleading.

“It’s not that elephants are killing every day. When deaths happen, they often occur in a very short span, minutes or hours, when people rush out after an initial attack.”

One person steps out, is attacked. Others follow in panic. The same herd strikes again.

EMERGENCY ACTION ON THE GROUND

Right now, forest teams are doing everything possible to contain the damage. Over 70–80 trained personnel are tracking the herd, guiding it away from villages and attempting controlled movement.

Immediate steps include radio-collaring, monitoring, and translocation to safer zones where possible.

At the same time, relief reaches families quickly. In case of death, ₹4 lakh compensation is provided: ₹1 lakh immediately, with the remaining ₹3 lakh released after formalities within a week to ten days.

A LONG-TERM PLAN TAKING SHAPE

Beyond crisis management, Kumar is pushing structural change.

For the past two years, the forest department has mapped elephant migration routes across the state, overlaying data on crop damage, human deaths, and conflict zones. That mapping now guides action.

Key plans include:

- Habitat enrichment with assured food and water

- Creation of corridors to restore natural movement

- Three dedicated elephant rescue and response centres, in the Ranchi–Hazaribagh–Ramgarh belt, Dumka region, and another strategic zone

- Fully equipped facilities with tranquilisation gear and trained veterinary teams, including women vets

- Community training on what to do, and what not to do, when elephants enter villages or approach homes

“Training people is critical. Not just to stay alert, but to know how to react if an elephant comes close to a house or field,” Kumar told Indian Masterminds.

BETWEEN FEAR AND FORESTS

Jharkhand’s elephant crisis is not a simple story of wildlife aggression. It is a story of broken habitats, stressed animals, frightened villages, and a state struggling to restore balance.

At its centre, Sanjeev Kumar is trying to slow the spiral, one corridor, one rescue centre, one village at a time, before more nights end in grief.