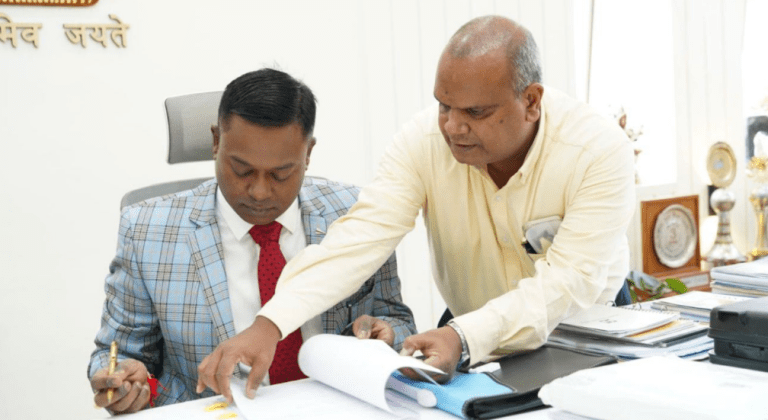

After years of walking alongside the Asiatic Lion in Gir, 2005 batch IFS officer Sandeep Kumar has now been entrusted with another frontier: Kachchh, one of India’s most enigmatic landscapes. As the Chief Conservator of Forests here, his canvas is vast and varied: from arid deserts that hold the secretive caracal to sprawling salt flats where flamingos paint the horizon pink to ambitious plans of welcoming back the cheetah.

“It’s a different kind of wilderness here. Kachchh doesn’t reveal itself easily. Its beauty is stark, silent, and layered. Protecting this fragile ecosystem is as much about patience as it is about action,” he shared while exclusively speaking with Indian Masterminds.

CONSERVING THE DESERT’S GHOSTS

Among the most elusive inhabitants of Kachchh is the caracal, a medium-sized wild cat known for its black-tufted ears and lightning reflexes. Rarely seen and often misunderstood, the caracal has been on the edge of oblivion in India. For Kumar, its survival is a litmus test of how deeply conservation can penetrate landscapes often written off as barren.

“To conserve the caracal is to conserve the entire desert food chain,” he says. “If this predator thrives, it means the prey base, the vegetation, and the habitat are all intact.”

Under his watch, research and mapping efforts are underway to create dedicated caracal conservation zones within Kachchh, putting this desert cat on India’s conservation radar.

WHERE THE SKY TURNS PINK

Every winter, the Rann of Kachchh transforms into a theatre of wings when tens of thousands of flamingos arrive to nest and feed. This spectacle, one of the largest in Asia, is both breathtaking and delicate, threatened by climate change, unregulated tourism, and habitat degradation.

For Kumar, the flamingos represent not just avian beauty, but the pulse of an ecosystem that thrives on seasonal cycles of salt, water, and migration. “When the flamingos come, they bring life to the Rann. They are nature’s reminder that even the harshest landscapes are alive and interconnected.”

Efforts are being made to strengthen monitoring of nesting colonies, regulate eco-tourism, and involve local communities in protecting these winged visitors.

THE RETURN OF THE CHEETAHS

But perhaps the most ambitious idea tied to Kachchh’s future is the possibility of reintroducing the Cheetah, the fastest land animal, into its open scrublands. While cheetahs have already made a return in Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park, experts have long believed that the vast Banni Grasslands of Kachchh could also serve as a suitable habitat.

Kumar sees this not as a faraway dream but as part of India’s broader rewilding vision. “The idea of Cheetahs in Kachchh is bold,” he reflects. “But if landscapes are restored and communities are partners, nothing is impossible. The grasslands deserve their predator back.”

CONSERVATION WITH PEOPLE AT THE HEART

What makes his work stand apart is his belief that conservation cannot be fenced off from people. Kachchh’s communities, including pastoralists, salt workers, and farmers, have all lived in harmony with the desert’s rhythms for centuries. Kumar’s initiatives seek to align conservation goals with their livelihoods, creating community-based monitoring groups and exploring eco-tourism models that benefit locals directly.

“In landscapes like Kachchh, people are the biggest allies. If they see value in conserving wildlife, it automatically becomes sustainable,” he shared with Indian Masterminds.

A FRONTIER OF CHALLENGES AND POSSIBILITIES

The task ahead is far from simple. Kachchh faces the dual pressures of industrial expansion and climate change, threatening its fragile balance. Yet, in every challenge, Kumar sees an opportunity to rethink conservation. His vision is not limited to protecting individual species but to nurturing an entire landscape of coexistence.

As he puts it, “Whether it’s a lion in Gir or a caracal in Kachchh, the goal remains the same: to ensure that India’s wild heritage doesn’t just survive but thrives.”