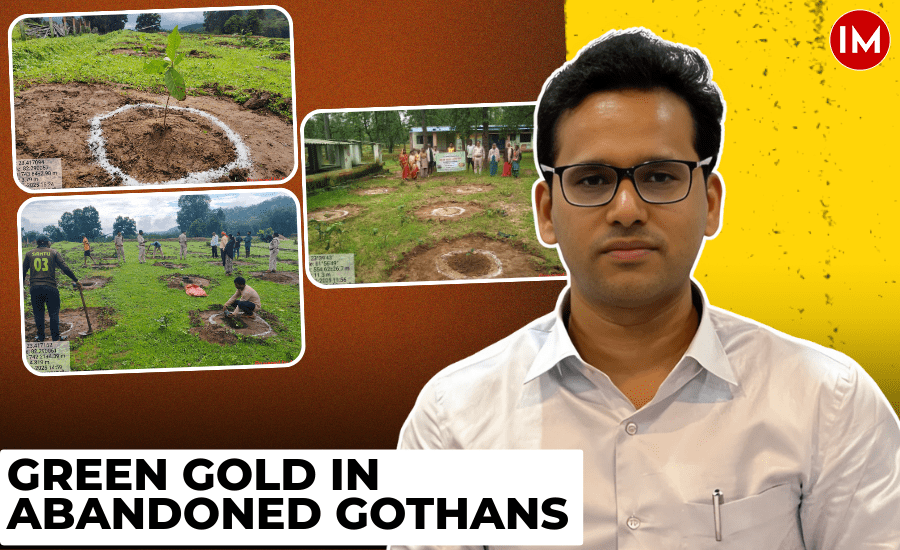

Across rural Chhattisgarh, thousands of gothans built during the previous government’s tenure remained abandoned. Many lay empty, encroached upon, and vulnerable to misuse, failing to serve the communities for which they were intended. To address this challenge, the Manendragarh Forest Division launched the “Mahua Bachao Abhiyan” (Mahua Conservation Campaign), planting mahua trees in these vacant spaces to create green, productive areas that benefit villagers while restoring ecological balance.

“Most of these gothans were built at a huge cost but remained unused. We saw an opportunity to make them productive again while contributing to the environment,” IFS officer Manish Kashyap, Divisional Forest Officer of Manendragarh (2015 batch, Chhattisgarh), shared in a conversation with Indian Masterminds.

REPAIRING AND PROTECTING GOTHANS

One of the initial challenges was the state of the gothans themselves. Fencing meant to protect these areas had been stolen or damaged over time. “We started by repairing the fences, ensuring these spaces are safeguarded. Without proper protection, any plantation would have been vulnerable,” Mr Kashyap explains. Once secured, the forest department began planting mahua saplings, ensuring that these lands would no longer be wasted or encroached upon.

Mahua trees hold immense cultural, economic, and environmental importance for tribal communities, particularly in Bastar and Sarguja. A single mature tree produces around two quintals of flowers and 50 kilograms of seeds, which translates to an annual income of about ₹10,000 for a household. Beyond financial benefits, these trees prevent soil erosion, help retain moisture, and maintain soil fertility, directly supporting agricultural productivity.

“Every part of the mahua tree has value. Conserving it is not just about planting trees but about sustaining the way of life for tribal communities,” Mr Kashyap emphasises.

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

The campaign has actively involved villagers from the very beginning. No Objection Certificates (NOCs) were obtained from Gram Panchayats, and local elected representatives participated in plantation drives. This participatory approach has not only protected the gothans from encroachment but also instilled a sense of ownership among villagers.

Declining mahua populations outside forests have been a growing concern. Young and middle-aged trees are rare because traditional land-clearing practices often destroy saplings, and complete seed collection prevents natural regeneration. Mahua trees, which can live up to 60 years, need systematic planting to sustain local livelihoods. “We engaged the villagers from day one. Their support ensures the saplings are cared for and protected,” Mr Kashyap explains.

EXPANDING THE CAMPAIGN

The Mahua Bachao Abhiyan is not limited to gothans. Last year, 30,000 tree guards were distributed for home planting, and saplings were planted in kitchen gardens and other community spaces. This year, over 112,000 saplings have already been planted, showing growing enthusiasm among villagers. The initiative aligns with the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s guidance to prioritise mahua in afforestation programmes.

Mahua trees are culturally significant for tribal communities. During the flowering season, villages come alive as families collect flowers and seeds for consumption and sale. Known as a “Kalpavriksha” or wish-fulfilling tree by some communities, mahua trees provide food, medicine, and income. They remain one of the few tree species preserved outside forests, highlighting their unique status in local traditions.

“In the next decade, these vacant spaces will transform into productive groves. Villagers will benefit, forests will expand, and mahua trees will continue to support livelihoods for generations,” Mr Kashyap predicts.

A MODEL FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

“Seeing villagers plant and care for these trees is the real reward,” he says. The Mahua Bachao Abhiyan demonstrates how abandoned spaces can be transformed into productive green zones, combining ecological restoration with socio-economic benefits. It serves as a model that other districts and states can replicate to achieve similar outcomes.