Long before modern medicine and formal justice systems reached India’s remote forests, fear shaped belief. In many tribal societies, illness, death, crop failure or financial loss were explained not through science, but through superstition. Over time, this fear hardened into a brutal practice: ‘witch-hunting’.

In Dang, Gujarat’s only fully tribal district, the belief still survives. Women, often widowed, elderly, poor, or socially isolated, are branded as Dagari, witches accused of inviting disease, death, and misfortune. Once labelled, they are beaten, humiliated, boycotted, and sometimes pushed to suicide.

Despite laws criminalising the practice, witch-hunting continues quietly, hidden behind rituals, silence, and community pressure. What brings it to light today is Operation Devi, a sustained police initiative that has pulled dozens of women back from the edge of social death.

WHEN A CHILD FELL ILL, THREE WOMEN WERE CONDEMNED

In February 2025, Jamanyamal village slipped back into that ancient fear.

Raman Vaghmare, a young boy, had been unwell for weeks. His father, Dhanaji, exhausted medical options and turned to a local Bhagat (shaman). What followed was chillingly familiar. After chanting mantras and burning incense, the shamans declared the child was under the “shadow of a witch.”

That night, the entire village gathered. Women were forced to sit inside a tantric square. With eyes shut and voices raised, the shamans suddenly pointed at three women: Kalagha, Panki and Devali.

“They are witches. All suffering is because of them.”

The women were tortured through the night, beaten and forced to confess to crimes they did not understand. At dawn, bloodied and barely conscious, they were taken towards a river for a witch ritual. A passerby finally alerted the police.

The Dang Police intervened and rescued them. But the damage was already done. Devali could not survive the trauma. She died by suicide. Kalagha and Panki returned to their village alive, but socially erased, living alone, working silently in fields, avoided by everyone.

ABUSE BEGINS AT HOME: MANGALA’S STORY

For Mangala, the violence did not come from strangers, but from her own family. In October 2023, in Galkund village, the 48-year-old woman was accused of witchcraft after repeated illnesses and misfortunes in the household.

“People beat me saying, ‘Beat her so much that she dies,’” Mangala recalls. “I thought of ending my life by consuming poison.”

She and her husband were attacked in public, locked inside their home, and abused relentlessly. Children fell sick, animals died, and every incident was blamed on her.

Police intervention eventually stopped the violence. Mangala now lives peacefully with her family, but the scars of isolation remain.

A PATTERN THAT REPEATS ACROSS VILLAGES

Across the villages of Dang, the experiences of survivors reveal a chillingly similar sequence of events. Whenever illness strikes a household, an accident occurs, or a family faces financial loss, suspicion quietly turns toward women who already live on the margins. Widows, elderly women, or those without strong family backing are often singled out and blamed for misfortune they have no connection with. Fear and superstition replace reason, and accusation becomes easier than understanding.

Once a woman is labelled a witch, violence follows swiftly. Many are beaten, tortured, and dragged into public spaces where they are humiliated in front of the community. These acts are often carried out openly, with neighbours watching in silence, reinforcing the belief that the punishment is justified.

The abuse does not end with physical harm. Social boycott becomes a daily reality. Villagers stop speaking to the accused women, refuse to visit their homes, and even deny them water. This isolation strips them of human connection, making survival itself a struggle.

Over time, the constant fear, shame, and loneliness take a severe psychological toll. For many victims, the pressure becomes unbearable. Some attempt to end their lives, while others tragically succeed, seeing no escape from the harassment that surrounds them.

OPERATION DEVI: POLICING WITH PROTECTION AT ITS CORE

Recognising the scale of the crisis, Dang Police launched Operation Devi in 2023 under then SP Yashpal Jaganiya. Today, it is being taken forward by SP Pooja Yadav, who has expanded its scope beyond rescue.

“Witch-hunting is an old evil in Dang. Widows and women living alone were historically targeted. Through Operation Devi, we decided to treat these women as victims, not as offenders,” Ms. Yadav shared in an exclusive conversation with Indian Masterminds.

Under the initiative:

- Women accused of witchcraft are formally identified and protected

- Police provide legal support and ensure action against perpetrators

- Survivors are reintegrated into villages with dignity

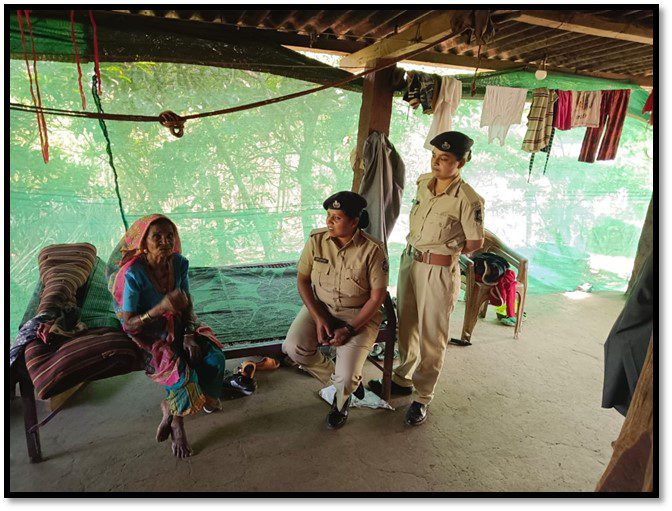

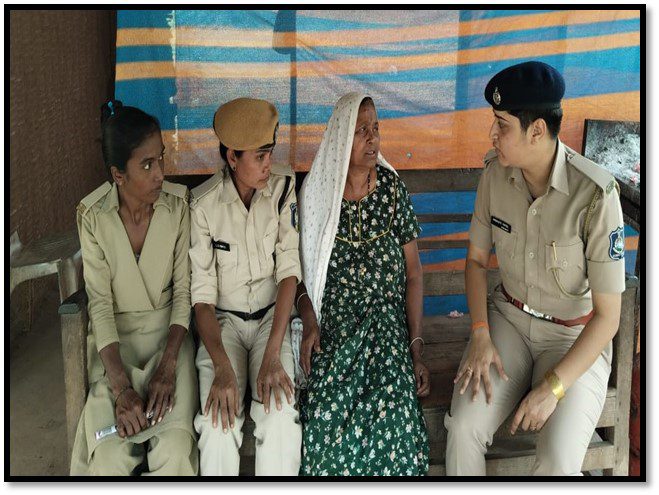

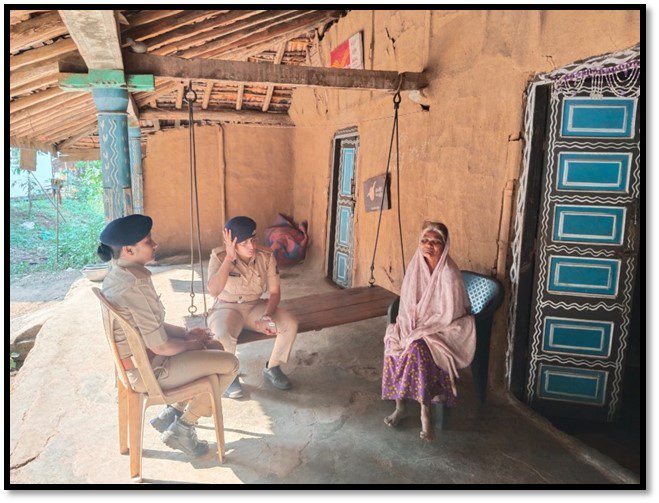

- A dedicated SHE team visits survivors every 15 days

Over the last two years, 64 women have been reintegrated into society.

FEAR HAS REDUCED, ACCEPTANCE IS THE NEXT BATTLE

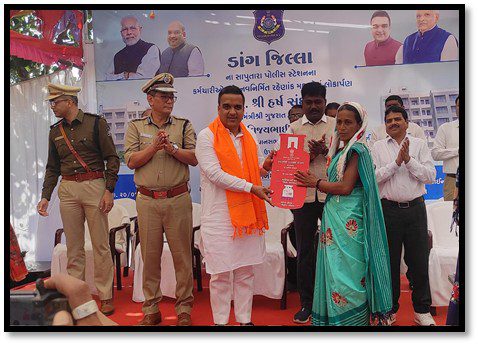

When SP Pooja Yadav took charge, Navratri was just days away. The previous year, 65 survivors had been honoured with certificates recognising them as victims.

“My immediate priority was to repeat it,” she says. “We identified new cases and found that within one year, the numbers had dropped sharply to only four to five women.”

Police presence has stopped overt violence. But silence remains.

“People are not disturbing them now,” she explains. “But they still don’t talk to them, don’t visit their homes, don’t even accept water from them.”

WATER AS A TOOL FOR SOCIAL HEALING

Dang is a water-scarce district. Ms. Yadav believes basic resources can help rebuild broken social ties.

“Our next step is social integration,” she says. “With support from NGOs, we plan to install water harvesting systems and borewells at survivors’ homes. When a household becomes a source of water, people will come. Conversations will begin.”

Alongside this, the police help survivors access government schemes, Aadhaar cards, and documents through the Samvedna Project, which works alongside Operation Devi.

“They had nothing – no documents, no identity,” Ms. Yadav told Indian Masterminds. “Our SHE team helps them with everything, from paperwork to emotional support.”

CHALLENGING SUPERSTITION WITH SCIENCE

Police and NGOs now conduct awareness programs explaining disease, accidents, and financial loss through scientific reasoning.

“If someone dies of malaria or dengue, it is not because of a woman,” Ms. Yadav says. “You cannot blame someone for your decisions or misfortune.”

Education, she believes, is a long-term solution. Residential schools and hostels are already changing the future for children, even if today’s victims cannot return to classrooms.

A SLOW BUT VISIBLE SHIFT

Today, Dang’s villages are quieter. The violence has reduced. Survivors live without fear of nightly attacks. The police are no longer outsiders, but protectors many women call family.

Witch-hunting in Gujarat is not folklore; it is a living reality. But with sustained policing, community awareness, and social support, Operation Devi is proving that even deeply rooted fear can be challenged.

The struggle is far from over. Yet for 64 women, survival has finally turned into a chance at life with dignity.