In Kozhikode, disability inclusion is no longer treated as an act of welfare. It is treated as a constitutional obligation.

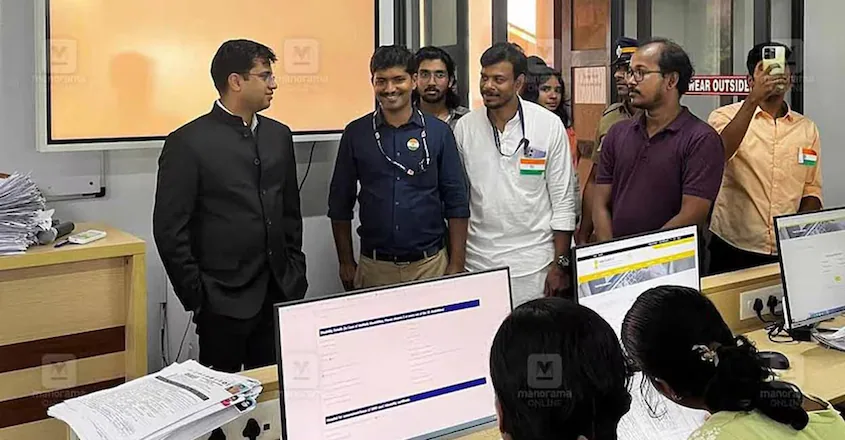

Under the leadership of IAS Snehil Kumar Singh, District Collector of Kozhikode, the district administration has built ‘Sahamithra’, a comprehensive, rights-based framework that places Persons with Disabilities (PwDs) at the centre of governance, not at its margins.

The idea was simple yet structural: if access to identity, healthcare, infrastructure, and dignity are guaranteed by law, then the administration must be designed to deliver them without delay, discretion, or dependence.

“We consciously moved away from fragmented welfare. Disability inclusion has to be systemic: anchored in data, delivered through communities, and owned by institutions,” Singh shared with Indian Masterminds.

The urgency was clear. The 2015 Kerala Disability Survey identified 78,548 PwDs in Kozhikode, nearly 2.41% of the population, making it the third-highest district in the state. Yet outdated records, pending certifications, and inaccessible systems meant thousands remained invisible to the state.

Sahamithra was conceived to change that… completely.

STARTING WITH THE DATA

Planning inclusive governance without reliable data is guesswork. Kozhikode addressed this gap by integrating Thanmudra, the state-level disability survey under the Kerala Social Security Mission, as the backbone of Sahamithra.

Rather than relying solely on digital mechanisms, the district adopted a community-driven data collection model. Over 2,800 Anganwadi teachers, supported by ICDS Supervisors, conducted physical household surveys, ensuring inclusion of families with limited digital access.

Within three months, the district covered over 58,000 individuals, creating one of the most reliable disability datasets at the district level.

“Accuracy comes from trust. When data is collected by familiar community workers, people participate openly,” Singh notes.

The result was more than a database. It became an administrative tool that allowed welfare schemes to be delivered as enforceable rights, not discretionary benefits.

ACHIEVING 100% UDID COVERAGE

For PwDs, the Unique Disability Identity (UDID) card is the gateway to entitlements. In Kozhikode, thousands were still without it.

Sahamithra addressed this through 33 Data Entry Camps across urban and rural areas, offering a single-window solution for:

- UDID registration

- Thanmudra data entry

- Application corrections and follow-ups

The effort mobilised 1,310 student volunteers from 18 colleges, NSS units, Campuses of Kozhikode, and DCIP interns.

The outcome was unprecedented. Over 57,777 individuals were enrolled, giving Kozhikode the distinction of becoming the first district in Kerala to achieve 100% UDID registration.

“Identity is not paperwork. It is access. Without it, rights remain theoretical,” Singh says.

FIXING THE BOTTLENECK

Medical Board certification had long been a choke point, marked by delays, travel burdens, and repeated hospital visits.

Using Thanmudra and UDID data, the administration identified 10,072 pending certification cases and organised 13 Special Medical Board Camps, strategically located to reduce travel hardships.

The results spoke clearly:

- 1,284 Medical Board Certificates issued

- Thamarassery: 134 approvals

- Perambra: 99 approvals

- Mukkam: 57 approvals

- Nadappuram: 134 approvals, 29 referrals

- Feroke: 116 approvals

By decentralising assessments, Sahamithra converted certification from a prolonged struggle into a time-bound administrative process.

TAKING CERTIFICATION TO THE DOORSTEP

For PwDs with severe mobility, financial, or access challenges, even decentralised camps were not enough. Sahamithra’s next innovation was the Mobile Medical Board Camp (Mobile MBC) model.

Through integrated datasets from UDID records, Kerala Social Security Mission, Unnathi, and hospital referrals, the district prepared a verified beneficiary list, shared with Local Self-Government Institutions (LSGIs).

The implementation plan is layered:

- Confirmation through calls and digital communication

- Preliminary screenings with ASHA workers, ward members, and PHUs

- Transport coordination by LSGIs where needed

- Doorstep assessments for persons with extreme mobility limitations

Over 720 beneficiaries across Corporations, Municipalities, and Panchayats are expected to be covered.

“No one should lose certification because they cannot reach us. In such cases, governance must reach them,” Singh told Indian Masterminds.

BUILDING ACCESSIBLE INSTITUTIONS

Rights matter only when physical spaces allow people to exercise them.

To embed accessibility into grassroots governance, Kozhikode launched the Differently Abled Friendly LSGI initiative. The first step was a district-wide Barrier-Free Audit using the ‘Yes to Access’ AI-enabled mobile application, aligned with the RPwD Act, 2016.

The audit examined:

- Parking and approach pathways

- Entrances and internal routes

- Toilet facilities

- Ramps, tactile paving, signage, railings, door widths, and surface safety

The scale was significant:

- 78 LSGIs

- Around 3,000 public buildings

- Participation from 80+ colleges, NSS units, and Campuses of Kozhikode

The findings now serve as a planning base for Panchayats to integrate accessibility into routine infrastructure development.

THE SAHAMITHRA MOBILE APP

Sahamithra also looks beyond certification, towards sustained care.

The Sahamithra Mobile Application, approved under the DARPG State Collaborative Initiatives (SCI) Scheme, is designed to support children with disabilities and their families, especially outside institutional therapy settings.

Currently in the final approval and work-order stage, the app will offer:

- Expert-designed home-based therapy guidance

- Personalised schedules and reminders

- Progress tracking and visual reports

- Direct communication with therapists, doctors, and special educators

- Integration with CDMCs and tertiary healthcare institutions

“Inclusion should not stop at hospital doors. Families need continuity of care at home,” Singh explains.

CHANGING LANGUAGE, CHANGING ATTITUDES

Sahamithra’s reach extends into public consciousness through sustained Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) campaigns across digital platforms, print, electronic media, videos, and posters.

One campaign directly addressed language, encouraging the shift from “Vikalaamgan” to “Bhinnasheshi”, reinforcing dignity-first communication.

CERTIFICATION MEETS REHABILITATION

To ensure convergence between documentation and support, ADIP facilitation counters were set up alongside Medical Board Camps.

Through ADIP Camps, over 350 PwDs received assistive devices, linking certification directly with rehabilitation.

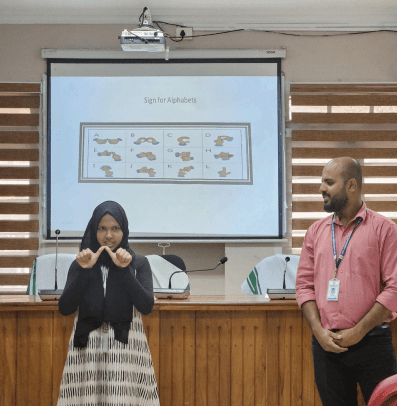

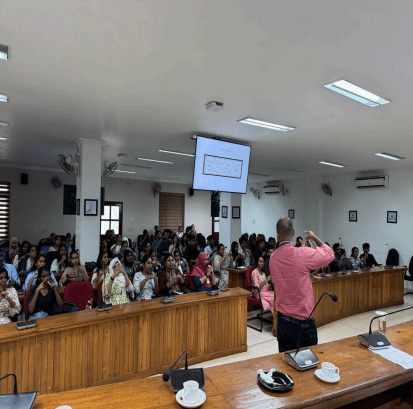

SIGN LANGUAGE AND ELECTIONS

Institutional capacity-building formed another layer of Sahamithra.

A Sign Language Workshop at the Collectorate trained 110 participants, including officials, interns, students, and faculty, with experts from CRC Kozhikode introducing Indian Sign Language (ISL).

In collaboration with the Election Department, CRC, and Social Justice Department, Kozhikode also ran an Inclusive Election Campaign:

- A Sign Language Awareness Video explaining the SIR process

- A dedicated camp enabling EVM voting for persons with visual impairment

Democratic participation, here, was designed to be accessible by default.

FROM POLICY TO EVERYDAY DIGNITY

Sahamithra is not a single programme. It is a governance architecture, where data informs action, communities drive execution, technology supports continuity, and institutions are held accountable to rights.

Under IAS Snehil Kumar Singh’s leadership, Kozhikode demonstrates that disability inclusion works best when it is treated not as a special initiative, but as a standard of administration.

“Our responsibility is to ensure that no person is excluded because systems failed to adapt,” Singh says.

In Kozhikode, those systems are now changing: methodically, measurably, and with people at the centre.