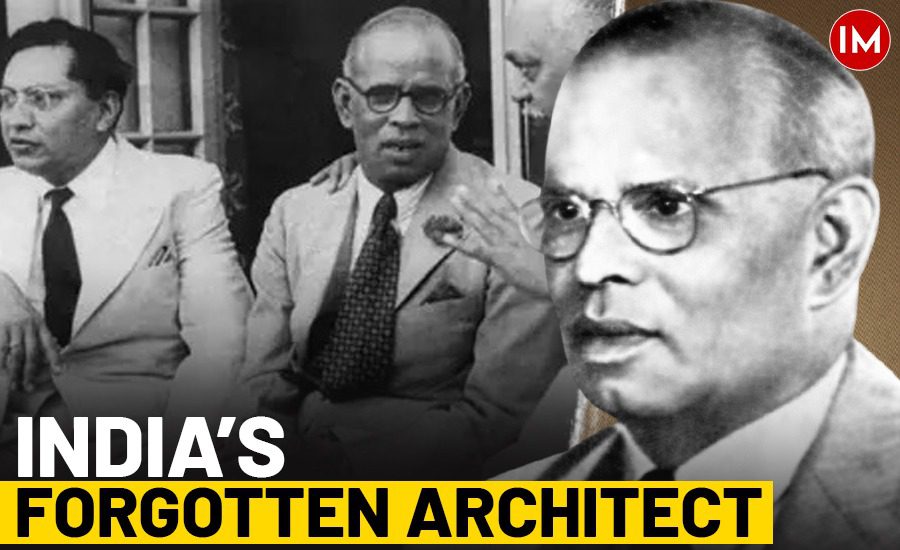

From a coolie in the Kolar mines to the architect of India’s political unification, Vappala Pangunni Menon turned constitutional theory into the foundations of the modern Indian state. His steady, unseen craftsmanship remains one of the great administrative achievements of independent India.

Who Was VP Menon

Vappala Pangunni Menon (1893–1965) occupies a rare place in India’s administrative history. Few civil servants have shaped a nation so profoundly, and fewer still have done so with such anonymity. As the subcontinent passed through upheaval in the 1940s, Menon – disciplined, meticulous, and fiercely intelligent – became the indispensable mind behind India’s transition to independence and its unification as a single political entity. For Legends of Bureaucracy, he stands out as a figure who shaped history not with speeches or charisma but with a mastery of draftsmanship, negotiation, and administrative design.

Career & Profile of VP Menon

Menon’s journey to the top was anything but conventional. Born in Ottapalam in present-day Kerala, he left school early and embarked on a life of hard labour and uncertainty. He worked at odd jobs across the country and even endured a stint as a coolie in the Kolar gold mines, an experience he later regarded as a formative lesson in resilience. It was chance—and a British official’s encouragement—that brought him to Delhi, where he secured a junior clerical position in the Imperial Secretariat. With no degree, no elite pedigree, and none of the privileges associated with the Indian Civil Service, Menon’s rise resembles what we might now call an early instance of lateral entry – a talent spotted almost by accident, refined through persistence, and elevated through sheer merit.

Role in India’s Unification

Inside the Secretariat, Menon proved his worth quickly. His superiors recognised an unusual clarity in his drafting, an instinctive understanding of constitutional matters, and an ability to remain steady under extreme pressure. Long hours spent taking notes during high-level negotiations gave him a ringside view of British policy-making, sharpening his understanding of the political and administrative machinery. He credited Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, for pushing him to think beyond the routine tasks of a clerk and engage deeply with the larger currents of governance.

By the mid-1940s, Vappala Pangunni Menon was serving as Constitutional Adviser and Political Reforms Commissioner to successive Viceroys. He drafted key proposals that shaped the transfer of power, including the plan that became the foundation for creating the two dominions of India and Pakistan. Working under punishing deadlines, he produced in mere hours documents that altered the destiny of the subcontinent. As India prepared for independence, years of unrelenting work left him physically drained, and he looked forward to retreating from public life once 15 August 1947 celebrations concluded.

But history had other plans. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, tasked with managing the politically explosive question of princely states, needed a mind capable of matching the scale of the challenge. The newly formed Ministry of States required both constitutional dexterity and psychological insight. Patel knew exactly whom to call. Menon, respected for his precision and incorruptible work ethic, became his Secretary. Their partnership—one of political will fused with administrative craftsmanship—would eventually redraw the map of India.

The challenge before them was immense. Over 500 princely states, varying wildly in size, governance, and ambition, had to decide their future. Some had their own armies, currencies, or postal systems; others were tiny clusters of villages. Many rulers were anxious or obstinate, and the subcontinent was already riven with communal violence and political distrust. Fragmentation loomed.

Together, Patel and Menon designed a solution that was elegant in its simplicity: the Instrument of Accession, through which rulers ceded control over defence, foreign affairs, and communications to the Indian Union while retaining internal autonomy. It was a masterstroke—legally sound, politically palatable, and adaptable to the needs of diverse states.

For more than two years, Menon travelled across the country, often making multiple trips a day, persuading rulers, calming fears, and offering a calibrated blend of cajoling and firmness. Where persuasion failed, the state acted decisively. Junagadh’s errant accession to Pakistan was reversed after Indian troops entered and a plebiscite confirmed the people’s desire to join India. The crisis in Hyderabad, where the Nizam sought independence, culminated in a police action. In Kashmir, Menon’s urgent intervention with Maharaja Hari Singh—awakening him to warn of tribal fighters advancing from Pakistan—led to J&K’s accession to India at a decisive moment.

By 1949, more than 500 princely states had been reorganised into a manageable set of political units—a feat unparalleled in scope and execution. As historian Narayani Basu notes in her biography V. P. Menon: The Unsung Architect of Modern India, “Patel’s open contempt for the rulers was tempered by Menon’s mix of subtlety, charm, and ruthlessness.” Together, they achieved what once seemed unthinkable: a unified India.

Beyond his administrative achievements, Menon’s writings remain essential for understanding the era. The Transfer of Power in India and The Story of the Integration of the Indian States offer a rare insider’s view of decision-making during the most turbulent years of India’s political evolution. Historians such as Rajmohan Gandhi, H. V. Hodson, Penderel Moon, and more recently Basu have drawn upon his notes, drafts, and recollections to illuminate how much of India’s unity owes to his steady, unseen labour.

Yet Menon’s legacy dimmed quickly after Patel’s death. Marginalised in the Nehruvian years, he receded from public attention. When he died in 1965, the funeral was small, quiet—much like the man himself. But the institutions he built endure. The structure of Indian federalism, the states carved from princely territories, and the very notion of unified sovereignty bear Menon’s imprint.

V. P. Menon remains one of India’s most consequential civil servants – not for occupying high office, but for reshaping the nation through administrative mastery.

Why VP Menon Matters Today

V. P. Menon’s story is more than an episode from India’s past – it is a reminder of what committed, capable bureaucracy can achieve. At a time when public administration is often associated with rigidity or caution, Menon’s career shows a different possibility: that a civil servant with clarity, courage, and craftsmanship can shape the destiny of a country.

His rise – from a mine worker to the chief architect of India’s integration – demonstrates that talent can emerge from outside formal systems. His work with Sardar Patel illustrates how strong political leadership and skilled administration together can produce nationdefining outcomes. And his writing, still studied today, reveals an official who understood both the mechanics and the meaning of state-building.

Menon matters because he exemplifies the best of public service: integrity without noise, competence without ego, and a legacy built not on headlines but on enduring institutions.