While passing through the far-flung villages in Baksa, close to the India-Bhutan border, 2016-batch IAS officer Aayush Garg, as the Deputy Commissioner of the district then, used to often stop to talk to the villagers. This gave him a chance to know first-hand about the problems they were facing. Whenever he asked them if he could do anything for them, invariably the request for an Anganwadi centre (AWC) would come up.

Not that this district in Assam didn’t have any, but those existing centres were scattered far and between, leaving many remote villages without one. This prompted Mr. Garg to make a plan to fulfil the villagers’ demand, and he decided on converging NREGS schemes to built the maximum number of Anganwadis within the shortest possible time.

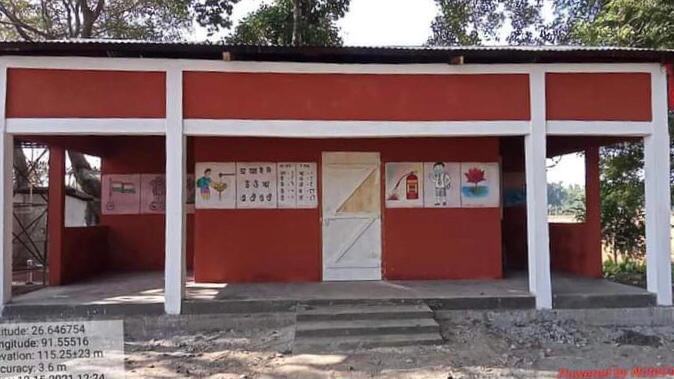

And, he did! He ensured that close to 200 centres were built within four months, using NREGS funds, prompting the Chief Minister of Assam to praise the model and ask other districts to replicate it.

Indian Masterminds spoke to Mr. Aayush Garg, who has since been posted in neighbouring Barpeta as Deputy Commissioner, to get more details.

GETTING TWO THINGS DONE WITH ONE SCHEME

Baksa district falls close to the India-Bhutan border, with many of its villages nestled near the foothills of Bhutan. The villagers are primarily from the Bodo tribe, with agriculture as their mainstay. The womenfolk, too, go to work in the fields and the young kids are often left to fend for themselves and take care of each other, with the older siblings taking on the role of the parents.

Hence, the need for Anganwadi centres was real and the villagers, especially the mothers, had conveyed it to Mr. Garg time and often, when he stopped at their villages while passing by, as was his habit. After giving it some thought, Mr. Garg decided on an ambitious programme to build 200 AWCs within four months through convergence of NREGS schemes.

Convergence is one thing which has been in discussion in governance for a long time. It is, basically, combining two or more schemes of the government under one programme and executing all the schemes under that one programme only.

“You do 2 plus 2, and get 5, not 4. Basically, you are getting two things done with one scheme. This way, you get more out of a scheme, than you’d have otherwise got. Convergence seems like an abstract idea when you read it on paper. But when you use NREGS funds to construct Anganwadis and see the assets shaping up physically on the ground, that is when you are able to say that convergence really works,” Mr. Garg said.

CREATED DURABLE ASSET

Primarily, construction of AWCs happen via NREGS funds only. However, no one usually undertakes it, since it is difficult to execute. Also, normally, the kind of schemes taken up under NREGS do not really produce quality assets.

“They don’t produce assets that you can showcase to someone five years or even a year down the line. So, this was our chance to create a durable asset; make good use of NREGS funds; and, most importantly, solve the issue of Anganwadis in the district. And, to broaden your perspective as an officer – if you can do it in this particular case, there are other avenues that you can explore on similar lines, where convergence is possible,” said Mr. Garg.

MAX NO OF CENTRES BUILT IN RECORD TIME

The construction of 200 Anganwadis was a Greenfield investment. And, the kind of funds necessary to construct that many centres, even in a year, is difficult to get from any state government. The districts have to make do with the allocation for constructing structures provided in the state budget, which, in this case, was not enough. However, instead of requesting the government for new funds, Mr. Garg made use of the NREGS funds. Looking back now, he says it involved a lot of manoeuvring and convincing the stakeholders, but they managed.

“That is how we were able to converge, and it served two purposes. One, we utilised the NREGS budget. And, two, we created an asset. One common problem with NREGS budget is, because of existing liabilities, it is difficult to execute. The Government of India often asks us that since we have spent so much money, can we actually show them something on ground which we have built? So, convergence solved that issue for us, as well,” Mr. Garg said.

WHAT MADE HIM DO IT?

Explaining what made him decide on this course of action, Mr. Garg said, “Our entire health as well as social welfare sectors are based on Anganwadis. A common pan-India problem is, there are no proper structures to keep the kids. Most of the time, they make do with makeshift arrangements. So, half of the parents are unwilling to send their kids to such centres. On top of that, the Anganwadi staff cite this as an excuse for not providing the basic services. So, we had to eliminate the common excuse to not perform. Also, when I visited the remote villages in Baksa, one of the persistent issues that came across was the lack of an Anganwadi centre.”

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION GAVE FURTHER PUSH

For constructing 200 AWCs at one go, there was the need for land. Although much of the land acquired for the purpose was government land, the surprise came in the form of voluntary donation of land by the villagers.

“This is why I am saying this was a genuine public demand. If you ask for land for any other purpose, they will not give it. When you get that kind of response, you become confident that you are going in the right direction. As government officers, the biggest matrix of evaluating public response is how enthusiastically they ask you questions and participate. When I enquired about land, 10 suggestions would come up from the villagers themselves,” Mr. Garg said.

The areas for constructing centres were selected on the basis of need. The Social Welfare department maintains a diary, and, on that basis, the villages that had the highest number of pregnant women and children below 6, and still did not have an Anganwadi, were chosen. The construction was done as per the drawing provided by the Social Service department, while, for the aesthetics, designs and drawings, the officer did crowd sourcing, roping in college students and NGOs.