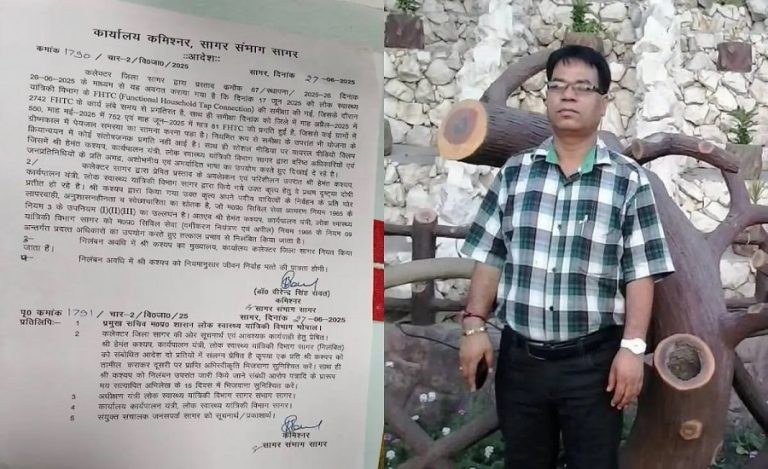

When IPS officer Ehtesham Waquarib took charge as Superintendent of Police, Jamtara, in August 2024, he wasn’t walking into the unknown. The district was already infamous across India, not for its landscape or culture, but for a darker distinction: it had become the country’s nerve center for cyber fraud. For years, scam calls and digital cons traced their roots back to this small district in Jharkhand. But Waquarib stepped in not just to maintain law and order; he came with a plan to pull Jamtara out of its murky reputation.

“I already knew what Jamtara stood for. So, I didn’t waste time. I went in with one purpose – to bring the numbers down, to dismantle what had become a system of digital deception,” he shared in an exclusive conversation with Indian Masterminds.

MAPPING THE FRAUD

His first move wasn’t action. It was understanding. Waquarib began by studying the structure of the cybercrime machinery – how it operated, who it targeted, and where it thrived. He tapped into the Pratibimb portal, a digital tool that gave the police real-time access to hotspot mapping and data analytics. The results were sharp and specific: two police station areas, Karmatand and Narayanpur, were where most of the fraud originated.

What followed was a clear-cut strategy. A special task force of 25 officers was formed. Their mission was to carry out raids not once in a while, but every other day, sometimes multiple times a week. Over the next six months, more than 200 individuals involved in cybercrimes were arrested.

These were not just arrests. They were signals. The message sent out across villages and towns was loud: the game had changed.

“Many of them fled. Others shut down operations. The calls dropped. The data told us what the street already knew, the network was breaking,” Waquarib says.

FLIPPING THE EQUATION

While raids were underway, another program was quietly building momentum: Operation Cyber Enjoy. It wasn’t just about catching criminals. It was about cutting off the roots that kept cyber fraud alive.

The operation was structured around three moves: aggressively raid and arrest criminals, connect with and influence the local youth, and counsel those who wanted to walk away from the crime world.

“We weren’t just filling jails. We were trying to make sure they didn’t get filled again by the next batch of teenagers looking for easy money,” he explains.

Rehabilitation and local engagement became the unexpected but necessary components in a place where cybercrime had almost become a default occupation.

A DIGITAL THREAT ON A NATIONAL SCALE

Among the many breakthroughs his team made, one stood out: a complex case involving malicious APK files. It was a national web of fraud disguised as a local hustle.

A team of cyber criminals in Jamtara had created malicious Android application packages (APKs) and sold them across India under the pretext of running local service centers. These apps weren’t harmless. Once installed, they could silently gain access to government schemes like PM-Kisan, bank account data, and private user information.

The attackers didn’t just scam people. They infiltrated systems, harvested data, and sold access to new scammers.

“Imagine getting an APK on WhatsApp from an unknown number. You tap it, and in seconds, they’re inside your phone. They can see your photos, read your emails, control your apps, and even send messages to your contacts pretending to be you,” he told Indian Masterminds.

The investigation uncovered a nationwide fraud racket, with possible losses running into Rs. 100 crores. The victims ranged from farmers in Andhra Pradesh to urban users in Mumbai. Within a month, his team cracked the case, arrested six key individuals, and recovered laptops and other devices tied to the scheme. The investigation is still active, but the momentum has shifted.

STAYING AHEAD OF THE TECH CURVE

In a crime landscape where technology evolves faster than enforcement can respond, Waquarib understood that old methods wouldn’t be enough. He made it a priority to hold regular coordination meetings with banks and SIM card providers, two of the most common enablers in digital scams.

Fraudulent SIM cards and fake bank accounts were often the entry points. If those were sealed, many scams would never take off. “We emphasized stricter KYC checks and kept communication lines open with telecom and banking officials in and around Jamtara. Everyone needed to be in the loop,” he says.

The idea was to make the ecosystem harder to misuse, not just to chase criminals, but to limit the tools they had access to.

CHANGING MINDS, NOT JUST NUMBERS

Even as arrests went up and scams dropped, Waquarib knew numbers alone didn’t mean success. The people who once ran these scams weren’t going away. Many of them were young, tech-savvy, and unemployed. He needed a counter-narrative, a way to bring change that would last beyond the next police raid.

So, he started with awareness. Every Saturday, he visited villages and small towns to speak about cyber safety. He directed police stations to conduct similar awareness drives twice a week. But lectures weren’t enough. He turned to local influencers, young people active on Instagram and YouTube, to help push a different message. That mobile phones could be tools for growth, not just traps for quick cash.

And then came something symbolic: an abandoned police station in Karmatand, turned into a library.

With support from locals and minimal funds, the building was renovated. Officers began volunteering to teach. Aspirants began to gather. The room once associated with fear became a place of ambition.

Waquarib shared, “That’s my favorite part. I studied in a library for UPSC. Watching others find that space again, in a town where fraud was once the norm, it means something.”

NO FINISH LINE IN SIGHT

Jamtara has slipped from the top five cybercrime hotspots to the 14th. But for Waquarib, it’s not time to relax. The nature of cybercrime is changing. AI, automation, and new tools are already shifting the threat landscape.

“The future of crime is online. That’s the plain truth. We have to keep updating our strategies, training our teams, and preparing for what’s coming next,” he stated.

For now, Jamtara is quieter. The calls have reduced. The libraries are filling up. And IPS Ehtesham Waquarib is still watching, still working, not waiting for cybercrime to return, but staying just a step ahead.