Beyond the intricate methodologies of Karnataka’s 2025 elephant census lies a story of resilience, adaptation, and vision. Conducted amidst the monsoon’s challenges, this operation faced logistical and environmental hurdles that tested the dedication of hundreds of forest staff. The census not only builds on decades of evolving techniques but also serves as a cornerstone for conservation, addressing the delicate balance between human and elephant coexistence. By examining the challenges, historical shifts in census methods, and the broader impact on population trends and conflict mitigation, this second part reveals how Karnataka’s efforts contribute to a sustainable future for its elephants.

CHALLENGES OF COUNTING ELEPHANTS

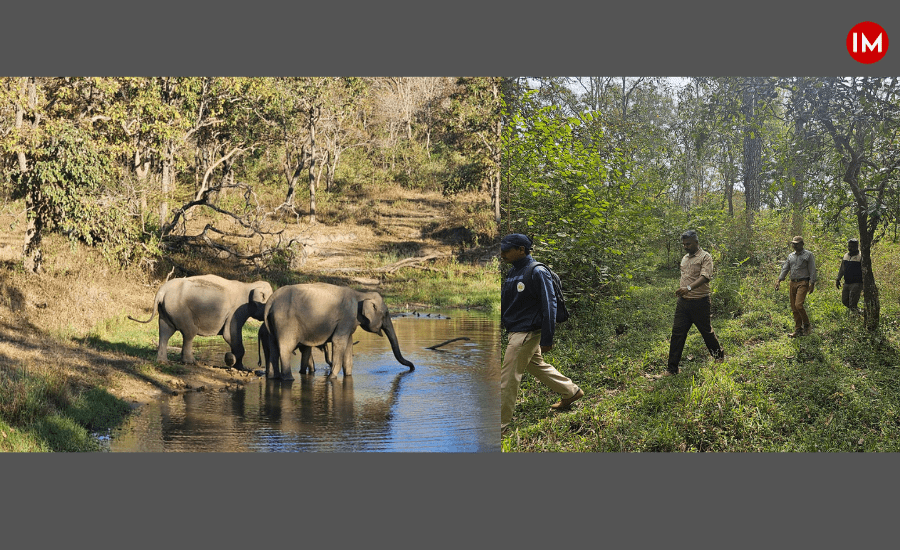

“Conducting an elephant census, especially during the monsoon season, presents significant logistical and environmental challenges. Arranging transportation for survey teams to remote beats, ensuring they reach the starting points of transects, and picking them up after completing 2-kilometre walks is a complex task,” Dr Ramesh Kumar P, a 2008-batch Indian Forest Service officer and Conservator of Forests (Project Tiger), Mysuru, told Indian Masterminds. Monsoon conditions make perambulating 5-square-kilometre blocks and walking transect lines particularly arduous, with muddy terrain and heavy rainfall hindering movement.

Additionally, elephants visit waterholes less frequently during the monsoon due to widespread water availability, reducing observation opportunities and complicating demographic assessments. These challenges require meticulous planning and coordination to ensure accurate data collection.

EVOLUTION OF ELEPHANT CENSUS IN INDIA

Historically, elephant censuses in India relied on the total/direct count method, where observers walked existing forest paths and counted elephants by sight. This approach lacked scientific rigour, especially for large landscapes with high elephant populations, as it was prone to errors and double counting.

The modern Sample Block Count Method, introduced to address these shortcomings, uses smaller, systematically surveyed blocks to increase detection probability and reduce errors. The addition of the Line Transect Dung Count Method provides an indirect estimate, corroborating direct counts, while the Waterhole Count Method offers demographic insights.

Nationally, elephant population estimation was conducted every four years until 2017, using the same trio of methods employed in Karnataka’s 2025 census. However, the Project Elephant Division of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) recognised the limitations of total counts and dung decay-based estimates.

“Since October 2021, the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) has been tasked with developing a more robust approach, adopting methods like dung-based DNA mark-recapture and camera trap-based distance sampling. This three-phase process includes beat-level surveys, habitat covariate collection, and intensive site monitoring with dung DNA and camera traps. As of 2025, Phases I and II are complete, with Phase III data collection and analysis ongoing,” the officer further informed Indian Masterminds.

In South India, synchronised censuses in 2022, 2023, and 2025 have continued using the established methods, providing consistent regional data. Karnataka’s 2025 exercise, focused on the Mysore Elephant Reserve, exemplifies this commitment to regular monitoring.

TRENDS IN KARNATAKA’S ELEPHANT POPULATION

Karnataka’s elephant population has shown notable fluctuations over the past decade, reflecting both conservation successes and challenges. According to the 2023 Synchronised Elephant Population Estimation by the Karnataka Forest Department (KFD), the state’s elephant population was estimated at 6,395 across 32 forest divisions and protected areas, with an additional 161 elephants counted in non-forest areas like coffee estates and private plantations. Key population estimates include:

- Bandipur TR: 1,116 elephants (density: 0.96/sq.km, area: 1,163 sq.km)

- Nagarahole TR: 831 elephants (density: 0.93/sq.km, area: 893 sq.km)

- BRT TR: 619 elephants (density: 0.69/sq.km, area: 897 sq.km)

In 2017, the All India Synchronised Elephant Population Estimation reported 6,049 elephants in Karnataka, with higher density estimates in some areas, such as Nagarahole (1.54/sq.km, 990 elephants) and Bandipur (1.13/sq.km, 1,170 elephants). The 2012 KFD estimation recorded 6,072 elephants, while the 2010 estimate stood at 5,740. These figures indicate a generally stable to slightly increasing population, with variations across reserves due to differences in habitat, food availability, and human pressures.

CONSERVATION AND CONFLICT MITIGATION

The 2025 census data is a vital tool for addressing human-elephant conflict and advancing conservation goals. By mapping elephant distribution in both forest and non-forest areas, the Karnataka Forest Department can identify critical habitats and movement patterns. This information is crucial for planning elephant corridors and buffer zones, ensuring safe passage between fragmented habitats and reducing encounters with human settlements. For instance, data on elephant presence in coffee estates and private plantations highlights the need for targeted mitigation strategies in these areas.

Demographic data from waterhole counts, including age and sex ratios, provide insights into population health. A balanced sex ratio suggests effective protection against poaching, particularly of male elephants for their tusks. The increase in elephant numbers over the past decade reflects successful conservation efforts, including habitat protection and anti-poaching measures. These synchronised counts also foster regional cooperation among southern states, ensuring a cohesive approach to elephant conservation.

By combining direct and indirect methods, the exercise provides a comprehensive picture of elephant populations, their distribution, and their demographic structure. As the Wildlife Institute of India continues to refine national estimation techniques, Karnataka’s data will contribute to a broader understanding of elephant populations across India. This knowledge is not only a foundation for conservation but also a critical step toward harmonising human and elephant coexistence in a rapidly changing landscape.