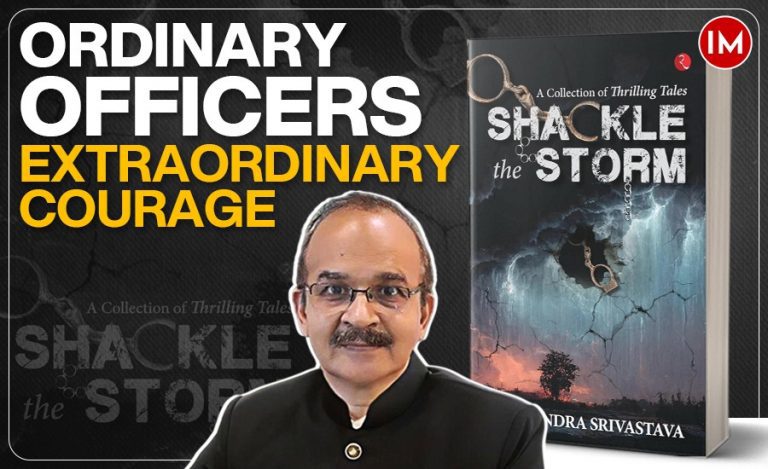

For bureaucrats pursuing their career on a linear path is like walking on a sword’s edge. While on the one hand, they have to ensure that rules are not violated and norms are met in their every decision. On the other hand, they have to keep their political masters in good stead.

It’s true that they have to face incessant political pressure, but the key to success is how a person deals with it. But they do not get publicized because few bureaucrats come out with such instances, even well after they have retired. One has to dig into autobiographies and reminiscences of retired bureaucrats to find such cases.

In his book ‘My Years with Indira Gandhi‘, Mr PC Alexander who worked as Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister from 1981 to 1984, has mentioned one such instance which goes on to show that one can stand up to even the Prime Minister of India. Herewith a few excerpts from his book office tenure as Commerce Secretary during Janata Party Government in 1977…

The Animal Farm

What came as a great shock to me was that within days of the advent of the Janata government, the same characters who used to try and exert pressure in Udyog Bhavan for undeserved favours started making their rounds, now using the names and influence of the new power centres and influence brokers in the Janata establishment.

Among various cases which I had to handle during my period as Commerce Secretary, I have to deal in some detail with a particular case which finally brought me into direct confrontation with Prime Minister Morarji Desai and his powerful Principal Secretary v Shankar and eventually resulted in my having to proceed on leave in 1978 and latter opting for retirement from service…

Import License in Permit Raj

…In 1963 the government had introduced an extra-promotional scheme according to which exports of certain non-traditional items could get import licence for certain high premium items like drugs, pharmaceuticals, etc., Up to 75% of the value of the export earnings. A particular group, which I shall call for purposes of this account X, claimed that they had exported over £ 500,000 worth of Zari goods to the UK and had become entitled to import licence up to 75% of the value.

But the flaw in their case was that only a small part of the export earnings has been accounted for in India and they had already received import entitlement for this. The bulk of the export earnings claimed by the firm as having accrued to them had not been repatriated to India and therefore they had no corresponding entitlement for imports. Non-repatriation of foreign exchange earned through exports was a grave offence and the firm was guilty of this offence on their own admission. Further, the export incentive scheme itself, had in the meantime, been withdrawn by the government. The Enforcement Directorate (ED) had started proceedings against the firm for violation of foreign exchange regulations and had advised the Ministry of Commerce against the issue of any import licence in their favour. The firm, however, had been persistently trying for several years to get the benefit of imports.

Pressure From The Minister

in February 1977 just a few days before the general election some people, claiming to be very close to the Commerce Minister, tried to bring pressure on me and my officers in the Import Control Wing to issue import licence to ‘X’ based on their old claim of export. On 25th February 1977, a message was conveyed to me purporting to be from DP Chattopadhyay, Commerce Minister, who was then on a long visit to Kolkata that he would like the file of X’s case to be sent immediately to his Calcutta camp with my recommendation that final orders could be passed by the Commerce Ministry without referring the case to the Finance ministry.

Obviously ‘X’ was trying to get an order from the Minister approving their claim for imports short-circuiting the procedure for getting the views of the Ministry of Finance. I sent the file to the Minister that very day but expressing my firm view that the case had to be referred to the ministry of Finance first. D.P. Chattopadhyay agreed with my advice, and the efforts of the interest parties to get licence issued in great haste were thus frustrated.

Pressure from PM’s office

But my troubles were to start again within days of the establishment of the Janata government. X soon found powerful support in the circles close to the Prime Minister and I came under strong pressure from V Shankar, his Principal Secretary, for issuance of the licence. I was surprised that the same group could apply their pressure tactics with the new government in such a short time and with such ease.

V Shankar sent for me and advised me to reconsider my stand on this case, dropping plain hints that he himself was under pressure to ‘do justice’ in this case. I explained to Shankar the facts of the case, thinking that he perhaps did not know its full background. But he knew all the facts and was determined to twist my arm and try to make me agree to do what was patently irregular.

He kept telephoning me, frequently advising me about the importance of giving clearance to the licence and expressing annoyance at my insistence on rejecting the firm’s claim as bogus. I wrote to Shankar on 8 May 1977 that since the Enforcement Directorate had advised that the party should repatriate the export proceeds first, they should take up their claim with that directorate.

Shankar was not the one who would give up nearly on grounds of legal niceties and norms. He started applying pressure on the Director of Enforcement in the Ministry of Finance to be ‘helpful’ and this had the expected result.

ED Buckled

Most surprisingly the enforcement directorate made a U-turn on its previous stand and sent a sort of clearance letter to the Commerce ministry, leaving us to decide the case as we assessed its merits.

I was indeed astonished that in a case involving a huge amount of foreign exchange the Directorate of Enforcement could be so flexible and so easily reverse its earlier stand.

But more surprise was in store for me. One day Shankar telephone me to say that the Enforcement Directorate had withdrawn its objection and I was the only one now standing in the way of X getting a licence. When I replied that Directorate had not given an unambiguous clearance he handed over the phone to the Director of Enforcement, who had already been summoned to his office and asked him to speak to me. The Director told me on Shankar’s phone that the issue of the licence was now entirely a matter for the Commerce Ministry to decide.

Minister Shows The Spine

I was not prepared to be a party to a decision which in my judgement was dishonest and I decided to bring the whole case to the notice of the new Commerce Minister, Mohan Dharia. In a note to him, I explained the hollowness of the party’s claim and personally briefed him about the pressures on me from the Prime Minister’s office.

Dharia fully supported my stand and assured me that he would stand by my decision. Shankar waited only for a few days to see whether I would relent.

After exhausting all efforts at pressurising me, Shankar one day asked me to see him in his office and told me that the Prime Minister himself would be writing to Mohan Dharia about this case and the Commerce ministry could, if they did not want to take a decision, refer the case to the Prime Minister’s office for its advice.

PM Gets Involved

I did not first believe that on a matter like this the Prime Minister could choose to intervene and I thought Shankar was mentioning the Prime Minister’s name only as part of the pressure tactics. But a letter promptly arrived from the Prime Minister on October 9, 1977 saying that the case has been pending for over 10 years and advising the Minister that it may be finally be disposed of in a fair and equitable manner.

The letter was intended to show the importance attached to this case at the highest level. However, it should be said to the credit of Mohan Dharia that he stuck to the stand that it would be inadvisable to issue any licence to X when they had not accounted for the foreign exchange claimed to have been earned through their exports and when they were under investigation for this very offence.

I knew that Mohan Dharia’s reply would only invite the wrath of the Prime Minister on me and I was now prepared for the worst. In fact, Mohan Dharia himself had told me that the Prime Minister had been making angry comments about me and asking why I was still continuing in the Central Government. The Cabinet Secretary Nirmal Mukherjee too had told me that the Prime Minister was very annoyed with me.

An Unequal Fight

Now that the prime minister himself had intervened in the case I knew that mine I was an unequal fight and I would have to to leave pretty soon. I decided that the facts should be recorded in a note to the cabinet Secretary before I was thrown out of my job. I requested the cabinet Secretary to put up my note to the Prime Minister so that I would have the satisfaction of making my stand on this case known to the highest levels in the government. Cabinet Secretary again want me that I should be prepared for the consequences. I knew that I would be thrown out of the ministry but it I would have the satisfaction of leaving at least a record of experiences I had to go through in trying to do what was correct and proper.

Nirmal Mukherjee later me informed about the Prime Minister’s reaction on reading my note. He felt outraged that an officer could write so boldly about his office and insisted that I should be removed from my post that very day.

Mukherjee told him that according to the decision already taken about pool IAS officers and that I could not be reverted to my home state at that stage as I had less than two years to retire. This made him very angry and he told the Cabinet Secretary that he was showing partiality to a fellow Christian.

Cabinet Secretary Resigns

Nirmal Mukherjee told Prime Minister that for the first time in his career he was being accused of communal bias and since the Prime Minister himself had done it, he considered it as an expression of lack of confidence in his objectivity, and it would, therefore, not be appropriate for him to continue as Cabinet Secretary. Nirmal Mukherjee offered his resignation orally then and there and followed it up with a letter.

Morarji Desai was not prepared for such a turn of events. He sent one of his trusted officers to Mukherjee, to assure him of his continued confidence in him and to ask that he should withdraw his letter, which he did.

The Fall Guy

I was at that time sharing a very important committee which was to recommend radical changes in import-export policies and procedures. The committee I had almost completed its work and was about to submit its report. Nirmal Mukherjee informed the Prime Minister that if I were to leave at that stage the committee’s work would suffer badly and it would be in Government’s own interest to allow me time to complete the report. Mohan Dharia also insisted that I should leave only after completing the work of the committee.

I felt severely let down and mortified at the treatment that was being meted out to me for trying to be honest. Here was a government which had come to power professing to uphold the highest standards of integrity, punishing and officer because he refused to be party to a dishonest deal.

Mohan Dharia fully sympathised with me in my predicament but told me plainly that he was helpless in this matter. The immediate thought that occurred to me was that I should quit without bothering as to what happened to the committee is work. I argued with myself that I had no need to sleep for a few weeks more to complete the work I had taken, after the way the government had treated me. But my own sense of duty finally prevailed and I completed the work of the committee by the end of January 1978. I presented the report to the minister on 31st January and the next day proceeded on leave.

I was very clear in my mind that he would not join service in my parent cadre in Kerala. I was the senior-most officer of the Kerala cadre of the IAS at that time. On another occasion when the Kerala Chief Minister Achyutha Menon had asked for my services for appointment as chief Secretary, Indira Gandhi had not agreed on the ground that he was holding an important assignment at the Centre.

Graceful Exit to UN

Now I was to go back to Kerala government as I was being unceremoniously thrown out of the central government. I thought it would be humiliating to go back to the state in such circumstances and decided to look for an opportunity for going for a short spell of UN service from where I could send in my letter of retirement from the highest with honour and dignity.

I had come away from the UN service twice before to work for my own Government and I was now being compelled to go back to the UN to preserve my self-respect.