In a quiet village office, far from Delhi’s power corridors, a silent revolution once began. There were no big slogans. No dramatic announcements. Just a simple decision — no cash, no cheque books, only digital records.

That decision would change how panchayats functioned.

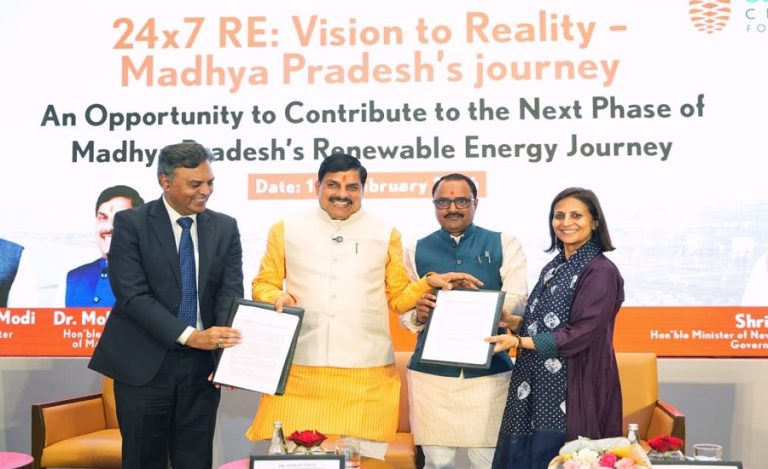

At the heart of this transformation was Dr. Aruna Sharma, a 1982-batch IAS officer of the Madhya Pradesh cadre. A practitioner development economist, she later served as Secretary, Ministry of Electronics and IT, and Secretary, Steel, Government of India. But one of her most impactful contributions came much earlier — when she helped digitise governance at the grassroots.

In a conversation with Indian Masterminds, Dr. Sharma spoke about how data, discipline and digital tools reshaped rural administration.

Read More : The Courage to Begin Again: Akash Verma’s Journey to UPSC AIR 20

BUILDING GOVERNANCE ON DATA

The reform began with a simple question: How do you ensure that benefits reach the right person?

Dr. Sharma believed the answer lay in creating a Common Household Database. The idea was to identify every family. Map their details. Link them to schemes. And avoid duplication.

“For all beneficiary schemes, you need to know the household,” she explains.

Using Census data and caste surveys, a clean database was built. Each household was given a logical identification number. Basic details were verified by officials. The first few columns were frozen to prevent manipulation.

This database became the backbone of welfare delivery. Scholarships, pensions, housing, employment — all were linked to this system.

When Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) expanded, payments went straight into bank accounts. Leakages reduced. Ghost beneficiaries disappeared.

The model later came to be known as “Samagra” in Madhya Pradesh. Several states adopted variations of it.

NO CASH, NO CHEQUES: PANCHAYATS GO DIGITAL

The real resistance came when panchayats were told to stop cash transactions.

“You will not have any cheque book. No cash transaction. Everything will be digital,” Dr. Sharma recalls.

Initially, there was opposition. Panchayat officials were unsure. Many feared audits. Some lacked technical skills.

But the reform had political backing. District Level Bankers Committees mapped villages. Bank accounts were opened within a five-kilometre radius. Post offices and cooperative banks were included.

Then came a smart administrative move.

Instead of forcing panchayats to maintain multiple audit registers, software was developed. Officials only had to fill two basic entries — cash register and work register. The system auto-generated the rest.

“By making just these two entries, the derivatives were automatic,” she says.

Suddenly, compliance became easier. Transparency improved. Even less educated sarpanches began supporting the reform.

“Now the full track of money is there. Nobody can accuse us of bungling,” she shares, recalling their reactions.

SAVINGS, SURPLUS AND STOPPING FRAUD

Digitisation uncovered hidden inefficiencies.

Closed schemes had unused funds lying idle. Incomplete projects were abandoned midway due to lack of funds. A detailed audit divided the state into zones. Chartered accountant firms examined panchayat records.

The result was surprising.

Surplus money from dead schemes was redirected. District Planning Committees were empowered to use it to complete stalled projects. School buildings were finished. Roads were cemented. Drainage improved. Housing quality increased. Digitisation also stopped scholarship fraud. Earlier, students enrolled in multiple colleges and claimed multiple scholarships.

“The moment it was digitised, this racket was completely stopped,” Dr. Sharma notes. Savings were significant. Funds could now be redirected towards genuine beneficiaries.

GEOTAGGING AND CONVERGENCE

Another reform was geotagging of works. Every road. Every building. Every toilet. Tagged and recorded.

Panchayats could now converge funds from multiple schemes. Money from MGNREGA, State Finance Commission and Central Finance Commission could be combined for better infrastructure.

“Everything accounting became very easy,” she says.

Villages began seeing visible change. Cemented lanes. Better sanitation. Quality toilets. Stronger housing. Digital systems made planning smoother. Audit stress reduced. Confidence increased.

Eventually, the Centre adopted a similar accounting model nationwide. Today, digital panchayat accounting is part of India’s rural governance framework.

SDGS: BEYOND RHETORIC

Dr. Sharma believes the same system-based thinking is needed for achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“By 2030, we will not be able to achieve them if we continue with a silo approach,” she warns.

She argues that 11 of the 17 SDGs are household-linked — poverty, nutrition, education, health, gender equality, sanitation. Without a Common Household Database, targeting remains weak.

“SDG is achievable. It is not about postponing by another 20 years,” she says firmly.

She points to global trends. Some European nations are moving towards structured databases. Many African countries still struggle with basic data systems. Her belief is simple: better data leads to better targeting. Better targeting leads to inclusive growth.

“No one is left behind means you must identify who is left behind,” she says.

GOVERNMENT VS CORPORATE: A DIFFERENT CANVAS

Having worked in both government and corporate sectors, Dr. Sharma sees a clear difference.

“When you work in government, your canvas is 1.43 billion people,” she explains.

The goal is public welfare. Stakeholder benefit. Long-term sustainability. In corporate roles, the focus is profit and shareholder value. Both require discipline. But governance carries a wider social responsibility.

INDIA’S BIGGEST STRENGTH

Looking back at four decades of service, she sees progress. India moved from famine conditions to food surplus. Institutions strengthened. Rights-based frameworks expanded.

“We have very good institutions. We must ensure we don’t dilute them,” she cautions. But challenges remain. Per capita income is still low. Growth must be inclusive.

“Population should become an asset, not a liability,” she says.

Her message is clear. Systems matter. Data matters. Institutions matter.

From digitising panchayats to reimagining SDGs, Dr. Aruna Sharma’s journey shows that real reform is rarely loud. It is methodical. Structured. Patient. And when done right, it changes lives — one household at a time.

Read More : The Poet in Uniform: How IPS Officer Kantesh Mishra Found Strength in Words