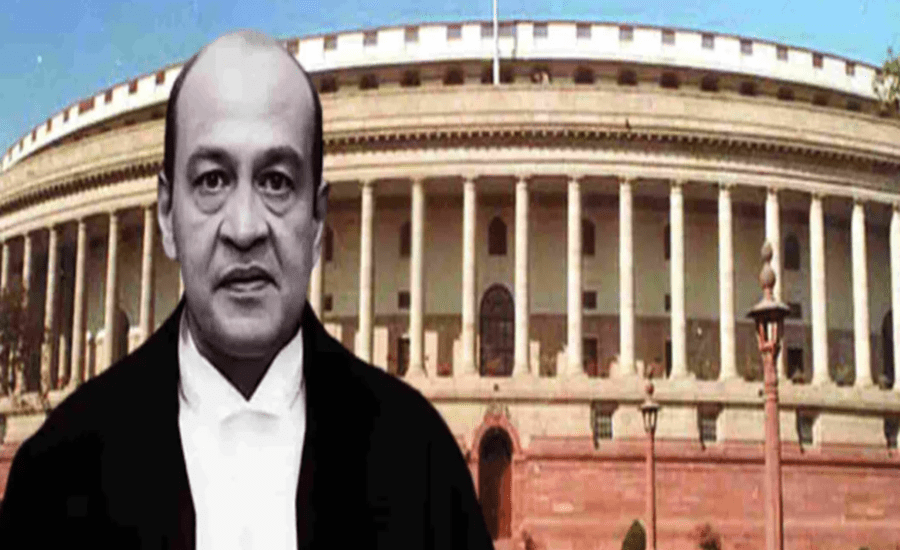

In a major development that has rocked India’s higher judiciary, a three-judge inquiry panel has recommended impeachment proceedings against Justice Yashwant Varma of the Allahabad High Court. The panel’s report cited strong evidence linking the judge to a suspicious fire incident at his official residence in Delhi, which led to the discovery of large amounts of burnt currency notes.

The inquiry committee — comprising Chief Justice Sheel Nagu (Punjab and Haryana High Court), Chief Justice G.S. Sandhawalia (Himachal Pradesh High Court), and Justice Anu Sivaraman (Karnataka High Court) — was formed on March 22, 2025, by then Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna. The panel concluded that burnt cash was found in the store room of 30 Tughlak Crescent, New Delhi — a government residence allocated to Justice Varma — and that the area was under the “covert or active control” of him and his family.

The fire occurred late on March 14, 2025. Firefighters and police officers responding to the emergency said they were shocked to find large heaps of burnt currency, primarily in Rs. 2,500 denominations, in a locked store room. One firefighter recalled seeing the cash on both the right-hand side and in front of him, calling the volume “alarming.”

Multiple witnesses, including emergency responders, captured stills and videos — some geotagged — that verified the presence of the currency. A viral video, confirmed to feature Station Officer Manoj Mehlawat, recorded him exclaiming, “Mahatma Gandhi me aag lag rahi hai,” referring to the image on Indian currency notes.

Findings by the Committee

The panel addressed three central questions:

- Was burnt currency found? Yes, supported by physical and digital evidence.

- Was the store room under Justice Varma’s control? Yes, it was part of his official residence.

- Did he provide a valid explanation? No, the panel found no plausible justification.

The report observed that even if Justice Varma was unaware of the precise activities, the presence of the cash at his residence represented a grave “breach of public trust.” It further noted that the burnt cash was allegedly removed the next morning by Justice Varma’s household staff and Private Secretary Rajinder Singh Karki, who also attempted to suppress evidence.

Justice Verma’s Defence

Justice Varma, who was in Bhopal during the incident, submitted a 101-page rebuttal in which he called the inquiry “unjust” and accused the panel of presuming guilt. He argued that he was made to defend against a presumption instead of facing direct evidence. He also questioned why CCTV footage was not obtained and raised concerns about a possible conspiracy to defame him.

However, the panel dismissed these claims as “unconvincing” and noted that there was no substantive material to support his conspiracy theory.

The committee, citing the Restatement of Values of Judicial Life (1997), emphasized that “probity” and “unimpeachable character” are essential for judicial officeholders. It concluded that Justice Varma had fallen short of these standards, undermining public trust in the judiciary.

Way Ahead

Justice Varma, who has since been transferred back to the Allahabad High Court, has not been assigned any judicial responsibilities. Despite the panel’s damning report, he has refused to resign or opt for voluntary retirement. The matter now awaits further action from the Supreme Court and constitutional authorities, which may initiate formal impeachment proceedings — a rare and significant step in India’s judicial history.

History of Judicial Impeachments in India

The impeachment of judges in India is governed by Articles 124(4) and 124(5) of the Constitution for Supreme Court judges, and Article 217 for High Court judges. These provisions empower the President to remove a judge from office on the grounds of proven misbehaviour or incapacity, but only after a rigorous process involving both Houses of Parliament. The procedure mandates that an address for removal be passed by each House with a special majority, which means it must be supported by a majority of the total membership of that House and at least two-thirds of the members present and voting. This stringent requirement is intended to protect judicial independence while ensuring accountability.

Over the years, only 5 impeachment proceedings have been initiated, though none have resulted in the actual removal of a judge by Parliament. Justice V. Ramaswami was the first judge against whom impeachment proceedings were initiated in 1993. Despite the inquiry committee finding him guilty of financial misconduct, the motion failed in the Lok Sabha as it did not receive the necessary two-thirds support. In 2011, Justice Soumitra Sen of the Calcutta High Court became the first judge to be impeached by the Rajya Sabha for misappropriation of funds during his time as a court-appointed receiver. However, he resigned before the matter reached the Lok Sabha.

In 2015, impeachment motions were initiated against Justice J.B. Pardiwala of the Gujarat High Court for his remarks on reservations, and against Justice S.K. Gangele following allegations of sexual harassment by a former district judge. While Pardiwala expunged the controversial remarks, leading to a withdrawal of the motion, the inquiry committee in Gangele’s case found insufficient evidence to proceed further. That same year, a motion was signed against Justice C.V. Nagarjuna Reddy of the Andhra Pradesh and Telangana High Court for alleged misconduct, but it did not progress beyond the preliminary stage.

In 2018, several opposition parties proposed a motion for the impeachment of then Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra, citing alleged corruption and abuse of authority. However, the Rajya Sabha Chairman rejected the motion on grounds of lack of merit, and the matter was not pursued further.

These episodes reflect the complexity and political sensitivity surrounding judicial impeachments in India. Although the constitutional framework provides a mechanism for removal of judges, the high thresholds and procedural safeguards ensure that this extraordinary power is exercised with extreme caution. So far, no judge has been formally removed by Parliament, though some have resigned under pressure before the process could be completed.