Republic Day in India is not only a celebration of the Constitution but also a public display of the nation’s military strength and organizational discipline. To understand the significance of the parade, one must look back through history. From ancient Mesopotamia to Rome, rulers have traditionally used military parades to showcase power and prestige.

Kings and generals marched through city gates, while captured soldiers, murals, and public ceremonies reinforced authority. Centuries later, modern military parades emerged in Europe, with Prussia pioneering formations and ceremonial marches, including the goose-step, which later became associated with Nazi Germany. Other nations, including China, Russia, and France, adopted similar traditions.

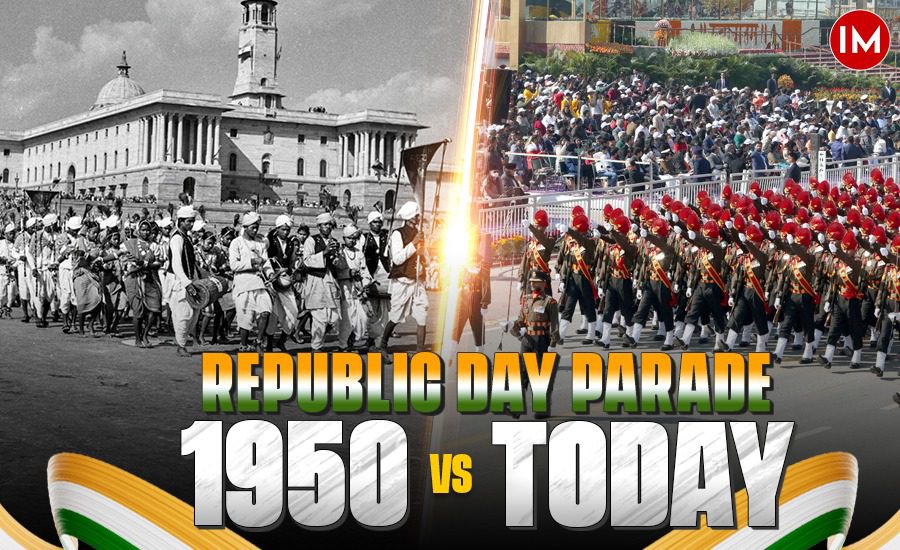

In India, the British Raj maintained regular royal parades and processions to display imperial dominance. After independence in 1947, India retained some of these ceremonial elements but gave them new meaning. When India became a republic in 1950, leaders decided that a parade on 26 January would serve as a symbol of sovereignty, marking the end of colonial rule and showcasing the young nation’s ability to protect its freedom.

Historian Dr. Srinath Raghavan noted in 2016 that “the republican tradition was an armed citizenry,” highlighting the parade as a reflection of India’s historical struggle for independence, achieved largely through non-violence, but balanced by the necessity of a disciplined defense.

FROM IRWIN AMPHITHEATRE TO RAJPATH

The first Republic Day parade in 1950 was held at the Irwin Amphitheatre, modest in scale. By 1955, the venue shifted permanently to Rajpath, forming the iconic backdrop for India’s military display. The ceremonial dais faces the parade, with troops presenting the national salute to the President. Early parades were simpler, featuring infantry, artillery, and cavalry. Over the years, new regiments, paramilitary forces, and civilian contingents gradually joined, creating a more elaborate procession.

THE MARCH PAST

The march past has been the centerpiece of the parade. In 1950, it consisted of infantry units and artillery formations, along with a fly-past by the Air Force. In later years, mounted sowars on horses, camel contingents, and mules carrying supplies from Gwalior’s mounted division were added, reflecting both India’s military diversity and regional traditions.

Women gradually began to take on visible roles. In 1960, Flight Lieutenant Gita Chand, India’s first woman parachutist, led a small group of airmen during the parade. Nearly six decades later, in 2019, Lt Bhavana Kasturi commanded an all-male contingent, cementing women’s place in one of India’s most visible military traditions. By 2024, the parade featured the first all-women Tri-Service contingent, the all-women Central Armed Police Force contingent, and women pilots, reflecting a wider inclusivity in the armed forces.

THE MECHANISED COLUMN: SHOWCASING INDIA’S DEFENCE CAPABILITIES

Over the years, the mechanised column became a highlight, displaying India’s military hardware. Tanks, artillery, and vehicles from the Indian Army’s corps of engineers and logistics regiments gradually replaced earlier mule and camel contingents. In 1960, the column included AMX light tanks, Centurion heavy tanks, and artillery guns, while the 1970 parade showcased Indian-made Vijayanta tanks and T-55 medium tanks, along with PT-76 amphibious vehicles.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the inclusion of missile systems, radar, and other technologically advanced equipment. The Prithvi missile, Arjun main battle tank, Snow Mobiles, Mine Protected Vehicles, and elite paratroopers became standard features. The 2020 parade highlighted India’s anti-satellite missile system, Mission Shakti, showcasing modern strategic capabilities.

FLY PASTS: DOMINATING THE SKIES

Fly-pasts have been integral since the first parade, although early post-independence regulations briefly banned them. In 1950, Wing Commander H.S.R. Gohel led a nine-aircraft Liberator formation. Subsequent years saw the evolution from subsonic aircraft to supersonic jets, including Toofanis, Canberra bombers, Hunters, MiGs, and Su-30 MKIs.

The fly-past is a visual culmination of the parade, ending with smoke trails in the national tricolor. Fuel shortages, wars, and austerity measures occasionally interrupted this tradition, but it has remained a symbolic and crowd-pulling element.

POLITICAL AND SYMBOLIC CHANGES

The parade has also mirrored India’s political and social evolution. In 1971, the Prime Minister began paying homage to the unknown soldier at the Amar Jawan Jyoti, commemorating those fallen in the Bangladesh Liberation War. Doordarshan broadcast the parade live in colour in 1983, expanding its reach to millions.

Recent changes include the renaming of Rajpath to Kartavya Path in 2022 and the merger of the Amar Jawan Jyoti flame with the National War Memorial flame in 2022, consolidating India’s tributes to its martyrs. Statues of colonial figures, including King George V, were replaced with Indian icons, such as Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, reinforcing the shift from colonial legacy to national pride.

THE COST OF THE PARADE

The Republic Day parade has grown not only in scale but also in financial commitment. In the first decade of annual parades, expenditure by the Centre rose from a modest ₹18,362 in 1951 to ₹5,75,000 in 1956, reflecting the inclusion of more regiments, civilian participants, and government departments.

This upward trend continued steadily: by 1971, the cost had reached ₹17,12,000, increasing further to ₹23,38,000 in 1973, and by 1988, it had ballooned to nearly ₹69,69,159. During this period, ticket sales helped offset some of the costs, with revenues reported at ₹7,47,095 in 1986.

Since the 1990s, the Centre has been more guarded about reporting the total expenditure. In Lok Sabha replies, the government consistently noted that “as arrangements in connection with the Republic Day Parade in Delhi are made by the concerned Central Ministries and Departments, State Governments, Union Territory Administrations, Central Public Sector Undertakings, local bodies, and other agencies, it is not collated and exhibited under one head. Hence, it is not possible to assess the total expenditure.”

Despite this, ticket sale earnings provide a glimpse of revenue, rising from ₹10,45,720 in 1999 to ₹17,63,021 in 2008, which was still a fraction of the actual spending. An RTI revealed that in 2008, total expenditure had reached ₹145 crore, and by 2015, the cost of preparing for the parade had escalated further to ₹320 crore.

In more recent years, the Ceremonials division of the Department of Defence was allocated ₹1,32,53,000 for 2021–22, though the total cost remained undisclosed. Ticket sales during 2018–2020 averaged around ₹34 lakh annually, with numbers limited by COVID-19 restrictions.

By 2023, as crowds returned in full force, earnings from ticket sales were reported at ₹28.36 lakh, again highlighting that the scale and grandeur of the event far exceed the revenue collected from spectators.

Over seven decades, the parade has transformed from a modest display of 3,000 troops to a multi-crore spectacle, reflecting both India’s growing defence capabilities and its commitment to a highly visible celebration of its republic.

As the 77th Republic Day draws near, the parade stands as a reminder of how far India has come: a nation proudly marking its Constitution, honouring its defenders, and celebrating its unity and diversity on the world stage.