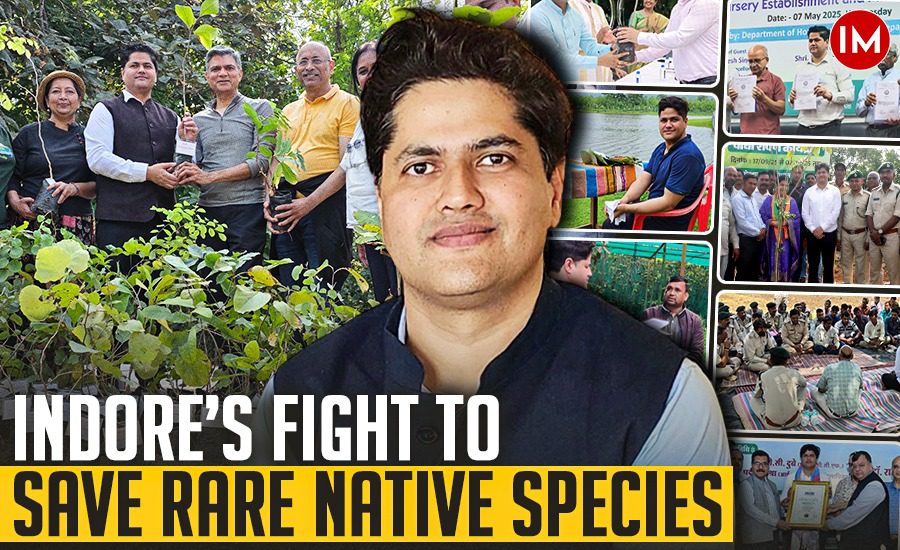

When Indian Forest Services officer Pradeep Mishra began reading old forest records of Indore, he was not looking to start a movement. He was simply doing his job. But buried inside four decades of data was a quiet warning — many native tree species had almost disappeared, without noise, protest or public concern.

That discovery would eventually place Indore on the global conservation map, with its RET Conservation Model now recorded in the World Book of Records, London.

A PATTERN THAT COULD NOT BE IGNORED

As Divisional Forest Officer (DFO), Indore Forest Division, Mr. Mishra ( IFS 2013, MP) studied nearly 40 years of Working Plan data. One trend stood out clearly. Several native species had fallen below 1% of the forest population, the forestry benchmark that classifies a species as Rare, Endangered or Threatened (RET) within a region.

“These were not minor species. They were the backbone of our forests,” he told Indian Masterminds.Trees like Haldu, Kusum, Arjun, Pakad, Anjan, Harra, Baheda and Bija — slow-growing, ecologically critical and culturally rooted — were fading away. Field visits confirmed the numbers. Natural regeneration was weak. Seed quality was declining. Climate stress and disturbance had taken a toll.

WHY THESE TREES MATTER

RET species play a silent but powerful role. They support soil health, groundwater recharge, forest microclimate, food chains and medicinal biodiversity. Losing them does not just reduce tree count — it weakens the entire ecosystem.

“What worried me most was that this loss was invisible,” says Mr. Mishra.

“There was hardly any discussion, no focused studies, and no priority in plantations.” Fast-growing and ornamental species dominated public spaces. RET trees were forgotten.

UNDERSTANDING RET THE RIGHT WAY

RET does not mean a species is rare everywhere. It is region-specific.

A tree common in one district may be endangered in another.

“This local understanding changed everything. Conservation cannot be generic. It has to respond to local ecology,” Mr. Mishra explains. That clarity led to the idea of a structured RET Conservation Programme for Indore.

WHERE DID RET TREES GO?

The decline had different reasons in different landscapes.

In cities, ornamental trees replaced native ones.

In villages, fuelwood use, informal timber sale and low awareness played a role.

In forests, RET saplings were planted but never tracked separately. Invasive species pushed them out.

“One solution could not work everywhere. We needed different strategies for different spaces,” Mr. Mishra says.

Read More: Across Pench, Kanha, and Beyond: Tracing the Journey of IFS Officer Dr. Sanjay Shukla

FIXING FOREST SYSTEMS FIRST

The first reform was simple but powerful — exclusive monitoring.

RET species were no longer mixed into general plantation data.

- Species-wise survival registers were created

- Dead plants were replaced immediately

- Field visits focused only on RET trees

“This ensured RET plants were not lost in averages,” he says.

NURSERIES : THE REAL GAME_ CHANGER

Indore Social Forestry Division manages nine nurseries. Mr. Mishra turned them into conservation engines. The Residency Nursery, located in the city, was declared a Dedicated RET Nursery. RET sapling production rose from 2,000 to 50,000, targeting 58 identified RET species.

“Without supply, awareness means nothing. We fixed supply first,” he says.

COMMUNITIES TAKE THE LEAD

With 117 Joint Forest Management Committees (JFMCs), Indore already had a strong base.

The department:

- Trained 40 active JFMCs

- Encouraged RET seed collection

- Supported micro-nurseries

- Allowed sale of excess saplings

“This made conservation local and practical. “RET trees became a source of pride and income,” Mr. Mishra notes.

People wanted native trees, but could not find them.

An old forest campus nursery was revived and handed to Nahar Jhabua JFMC. A Poudha Vikrya Kendra was opened. Now, citizens can buy RET plants and learn how to grow them.

BRINGING RET INTO THE CITY

RET plantations reached schools, colleges, hospitals, courts, parks and government campuses. Each plantation came with awareness sessions.

Cities, Mr. Mishra believes, are also ecosystems.

“Urban spaces must support native biodiversity, not just decoration.”

YOUTH BECOME CONSERVATION PARTNERS

Students of Holkar Science College compiled a list of 100 rare species and asked for training. An RET Demonstration Nursery was set up. Over 5,000 RET plants were grown on campus. Soon, Devi Ahilya Bai University joined in.

“Young people don’t just plant trees. They carry the idea forward,” he says.

SUPPORT FROM THE TOP

The initiative received backing from the Mayor of Indore, MLAs, MPs, NGOs and civil groups.It aligned with the CM’s Namo Van–Namo Vatika–Namo Upvan vision and the PM’s Meri LiFE Mission. Public planting by leaders helped spread the message.

TECHNOLOGY JOINS CONSERVATION

Indore also adopted LIDAR-based mapping and digital monitoring.

A pilot registry now tracks species, location, planting year and survival.

“This gives us long-term ecological memory,” says Mr. Mishra.

GLOBAL RECOGNITION, LOCAL ROOTS

The Indore RET Model has now been recorded in the World Book of Records, London. Several districts of Madhya Pradesh are replicating it.

But for Mr. Mishra, the real success is quieter.

“RET species are the genetic memory of our forests,” he says.

“If we lose them, we lose resilience, identity and balance.”

Indore’s journey shows that sometimes, the most important conservation work begins by listening carefully — to data, to forests, and to what is disappearing without a sound.