In a significant achievement under the flagship initiative Mission Sankalp, more than 10 villages in Tripura’s Sepahijala district have been awarded the ‘Aspiring Child Marriage-Free’ certification for successfully preventing child marriages over the past year.

Sepahijala, a border district sharing a long stretch with neighbouring Bangladesh, has long battled deeply entrenched social practices. Today, however, it is emerging as a model of grassroots action, driven by proactive governance and community participation aimed at ending child marriage and teenage pregnancy.

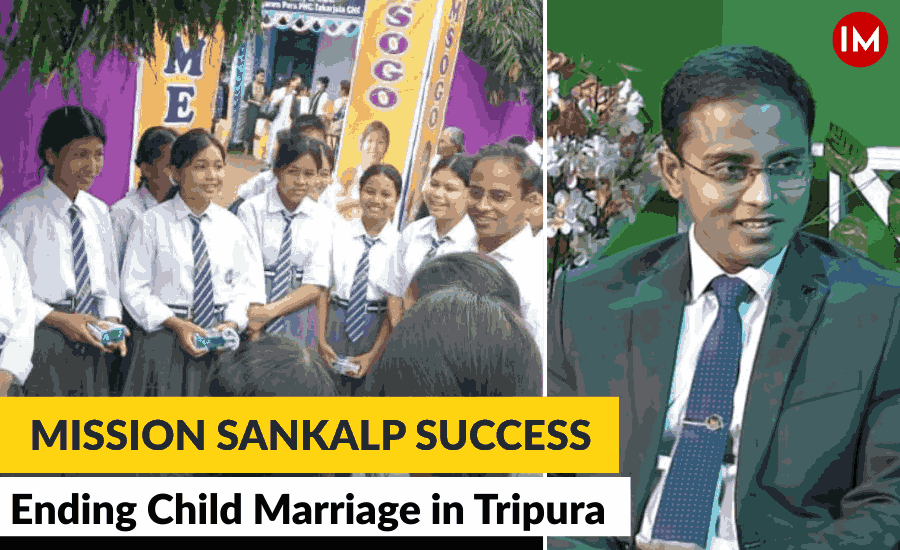

Indian Masterminds interacted with the brain behind this initiative, Sepahijala District Magistrate Siddharth Shiv Jaiswal, an IAS officer of the 2016 batch, to learn more about Mission Sankalp and its impact.

“At the district level, we decided we could not afford to treat child marriage as routine social behaviour,” says Mr Jaiswal. “It had to be confronted as a developmental and humanitarian crisis.”

A district facing a harsh reality

Behind the celebration lies a grim truth. According to the National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5), 51.9 percent of girls in Sepahijala are married before the age of 18, and 26 percent become mothers in their teenage years.

When IAS Jaiswal took charge as District Collector in July 2024, these statistics were no longer abstract numbers. Field visits revealed girls as young as 13 being pushed into marriage and early motherhood.

“These young girls were losing their futures before they even began,” Jaiswal reflects. “If we don’t act now, our demographic dividend will become a demographic burden.”

The man behind the mission

A doctor by training, IAS Jaiswal’s understanding of public health shaped his administrative vision. During his tenure with the National Health Mission amid the COVID-19 pandemic, he saw how child marriage quietly worsened maternal health outcomes. Later, as a Director in the Social Welfare Department, he encountered repeated cases of child rights violations.

“But in Sepahijala, the numbers turned into faces,” he says. “Girls who should have been in classrooms were preparing for marriage. Some were already mothers.”

Recognising that piecemeal solutions would fail, Jaiswal conceptualised a district-wide intervention – Mission Sankalp.

Mission Sankalp: breaking silos

Mission Sankalp was launched as a convergence-driven district mission, bringing multiple departments onto a single platform. The Social Welfare, Education, Health, Police, Child Welfare Committee, District Child Protection Unit, and Childline were all integrated into a coordinated response.

“The prevalence of child marriage here is extremely high,” Mr Jaiswal explains. “That’s why we adopted a convergence approach. No single department can tackle this alone.”

Under his leadership, regular reviews, shared accountability, and joint field interventions became the norm. Police and sub-divisional magistrates were empowered as Child Marriage Prohibition Officers, while NGOs, community volunteers, and media partners strengthened outreach and surveillance.

“We stopped working in silos,” Mr Jaiswal says. “Through the District Magistrate’s coordination powers, everyone started pulling in the same direction.”

Schools as early warning systems

One of Mission Sankalp’s most effective strategies was turning schools into early warning systems. A “six-day absentee rule” was introduced: if a girl student remained absent for more than six days, a joint team of teachers and administration officials visited the household.

“Often, absences revealed a looming child marriage,” Jaiswal notes. “If we sensed risk, we intervened immediately and explained why education must continue.”

The education department played a pivotal role, while health officials monitored adolescent pregnancies and maternal outcomes. Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) campaigns were conducted through schools, village meetings, and Village Health and Nutrition Days, slowly shifting social attitudes.

Law enforcement and fear of consequences

Alongside awareness, the administration made it clear that the law would be enforced. Injunctions under the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act were sought in individual cases, and FIRs were filed in 15–20 instances.

“We wanted people to understand that child marriage is not a private affair,” he says. “Even if a girl is married, any sexual activity with her is still a criminal offence under the law.”

Gradually, what was once socially accepted began to carry consequences. “There is now a visible hesitation,” he adds. “What happened openly before is now seen as a taboo.”

Innovation at the village level

Inspired by the Swachh Bharat Mission model, Jaiswal introduced a tiered certification system to motivate communities –

- Aspiring Village: No child marriage for six months

- Rising Village: No child marriage for one year

- Model Village: No child marriage for two consecutive years

“So far, we have awarded bronze certification to ten villages,” he says. “Eight of them have already progressed from Aspiring to Rising status.”

Public recognition, certificates of appreciation, and community pride created a healthy competition among villages.

Results that speak

The impact of Mission Sankalp is tangible. Since July 2024, over 150 child marriages have been prevented, and more than 130 children rescued from early marriage.

Health indicators are also shifting. The number of health facilities reporting zero deliveries among girls under 18 rose from four in December 2024 to 11 by March 2025.

“These numbers tell us that prevention is working,” Jaiswal says. “But more importantly, it means girls are staying in school and reclaiming their futures.”

A rescue that showed what was at stake

One such future belongs to Ruhi (name changed), a 14-year-old student who was rescued just days before being married to a old man. Acting on a teacher’s alert, officials intervened, provided counselling and rehabilitation, and ensured her continued education.

“Now I want to become a teacher,” Ruhi says, smiling. “I can study and play again.”

For IAS Jaiswal, stories like hers define the mission’s urgency. “Every rescued child reminds us why Mission Sankalp exists,” he says.

Looking ahead: a bold deadline

Jaiswal has set an ambitious goal – to eliminate child marriage in Sepahijala by 2027, three years ahead of the global Sustainable Development Goal target.

“Mission Sankalp isn’t just another initiative,” he says firmly. “It’s personal. It’s urgent. And it’s about safeguarding the future of our children and our nation.”

As Sepahijala’s villages move steadily toward becoming child marriage-free, the district stands as proof that determined leadership, community trust, and coordinated governance can rewrite even the most entrenched social realities.